Syria's exiled academics struggle to rebuild careers wrecked by war

Ghazzoul is an academic linguist from Syria who, like many others in her line of work, has been displaced due to conflict in her home country and is now struggling to continue her career.

At the time her car came under attack in 2011, it was the start of the Syrian war. Having supported herself through a PhD, a doctoral thesis, a graduate certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, an MA in Linguistics and a BA in English Language and Literature from universities in Syria and the UK, she returned to work at Aleppo University.

However, after the terrifying episode in the car she felt moving to Jordan and acquiring refugee status would be the best decision.

"Syrian academics were highly regarded in Jordan," says Ghazzoul.

"At some points academics were kidnapped for ransom in Syria. Then they killed them even if the ransom was paid. I was also scared for the safety of my son – that he may be kidnapped or arrested like other young men."

Academics in exile

Hundreds of thousands of other Syrians fled to Jordan to escape the war which put further pressure on a country already battling economic downturn and a high unemployment rate – currently at 19 percent. This in turn led to a change in attitude towards Syrian academics, says Ghazzoul.

|

|

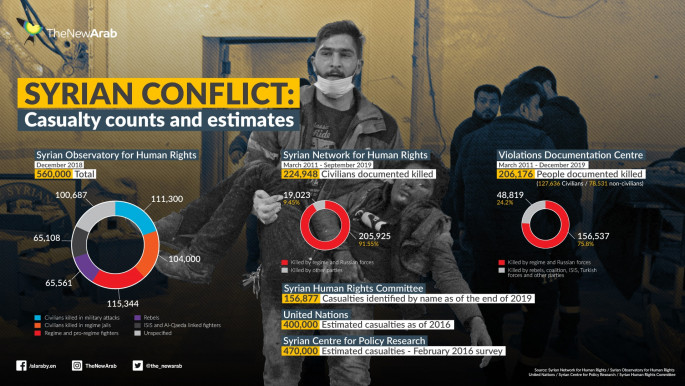

| Read more: Will we ever really know how many people have died in Syria since 2011? |

"Here we're overworked, we have little money, no rights, less chances to attend conferences in our industry, we're unable to travel or even to be engaged in scholarship opportunities like Fulbright," she says.

"There used to be 100 or more of us in Jordan but a lot of people have taken the risk of going to Turkey in the hope of more opportunities."

Ghazzoul says finding work to pay the bills is difficult enough and often left no time for her to continue her research, meaning she was forced to forfeit her career just so she and her family could survive. She says there is a massive gap in terms of support for displaced academics.

However, she is among the first cohort to enlist on a newly launched fellowship program for Emerging Displaced Scholars at Columbia Global Centers in Amman, Jordan, specifically focused on helping displaced scholars continue their careers. Fellows receive a stipend of $25,000 for the duration of the 12-month fellowship.

"The fellowship has been a lifeline for me," she says, outlining the programme she is now able to design which aims to improve Syrian graduates' education by increasing their understanding of English.

"I feel happy for the first time since I left Syria. I've restored my self-esteem. I can be productive and help others."

|

At some points academics were kidnapped for ransom in Syria. Then they killed them even if the ransom was paid -Nahed Ghazzoul |

|

Archaeologist Ahmed Fatima Kzzo, 36, is also among the fellowship cohort. When he left Syria to study his PhD at the University of Rome he never imagined returning to his home on a permanent basis would become impossible.

Having completed his BA in archaeology at the University of Aleppo in 2008 he chose to continue his education in Italy.

"A lot of European companies in my field were working in Syria at the time. There had been an Italian expedition working at the Ebla archaeological site in north-western Syria since 1964," he says.

"Syria was rich in archaeology and at the time I was still living there, public and newly-opened private universities offered a lot of job opportunities."

|

|

| Read more: Syria Weekly: Few options to end catastrophe in Idlib |

By the time he had finished his PhD, the war had started and he wasn't able to return. Apart from the obvious danger of being in Syria during the eruption of the conflict, Kzzo says universities were attacked, leaving no job prospects. The last time he visited was in 2011.

"At the beginning it was very difficult. Following the initial news of the conflict was very stressful," he says. "After six years I saw my father in Lebanon. He was very emotional which was unusual for him. Now he's asking to come here to visit but they tell me it's not easy."

Kzzo remained in Italy for a while before continuing his studies in Switzerland. Then in May last year he found out that he had won a place on the fellowship programme.

Unable to find a job in Europe, he says it was support he was desperately in need of. It has enabled him to continue writing his book on artefacts found in Ebla, near Aleppo, from the time of 2,000 BC to 1,000 BC which provide insight into ideology, religious beliefs, the administrative system and even the cultural rituals of the era.

Programme manager at Columbia Global Centers, Dr Ahmad Al-Mousa, says academics who face displacement are at risk of getting lost in the system. The fellowship program is a pilot that has been launched in partnership with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation – which has provided funding for four years – specifically aimed at aiding those working in the humanities and humanistic social sciences to reintegrate into academia.

|

They are the intellectual elite of their country and their country will be impoverished unless they can return and rebuild at some point -Stephen Wordsworth |

|

If it is a success they hope to roll it out in other countries which would make the course more accessible for those in need of it.

"Success is ensuring the scholars at the end really are up-skilled, have been provided the appropriate support so they can achieve what they've envisaged and that they've been able to build a network. Our job is to ensure we create an opportunity at the end of this," says Al-Mousa.

'Return and rebuild'

The Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara) in the UK is one of just three organisations worldwide that provide support for people like Ghazzoul and Kzzo, says its executive director Stephen Wordsworth.

"[The way the organisation operates] has changed enormously; it began as a mission to help people from Germany in 1933 in response to the Nazis coming to power," he says.

"Nowadays, we have many academics coming from the Middle East. It's a question of what's going on and why they need to get away. Syria has been the main source of people requiring our help for the last three years."

Read more: Refugees and democracy are dying at Europe's front door

Wordsworth explains academics aren't always necessarily threatened on an individual level – in some cases it could be their universities are attacked during conflict so they no longer have a place of work.

Equally, in Turkey, academics who signed a petition in support of the Kurds were dismissed or put on trial and, following the attempted coup in 2016, more than 100,000 state employees – including 8,000 academics – were reported to have been dismissed while more than 50,000 were imprisoned. In extreme cases their lives can be at risk.

"Like anyone else they need help, they are the intellectual elite of their country and their country will be impoverished unless they can return and rebuild at some point," he says.

"They're not coming here simply to be helped, they are bringing skills and knowledge with them and sharing it with host universities."

Cara is currently working with 300 people and has helped scholars from 25 countries including Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Bangladesh and Pakistan. It aims to keep people safe but also defend learning and science to ensure this knowledge is retained, says Wordsworth who adds that funding is a big challenge outside of the UK.

"Much of our funding comes from universities throughout the UK and when we ask them to host academics we look to them to cover costs. Because of the way universities are funded here they have substantial funds available, however, European universities are funded by the state and have less free funds," says Wordsworth.

Another issue is visa restrictions. Academics supported by Cara are not asylum seekers, he says. They are granted a three-year visa if completing a PhD but only a two-year visa for post doctorate research which is not renewable.

Read more: Human rights group documents forced disappearance of over 98,000 Syrians

"Doing a post doctorate, getting well established, takes time. Two years means they've hardly started before they have to start looking around for what they're going to do next," says Wordsworth.

He explains how one academic is developing a hybrid variety of wheat by combining strains from the UK and the Middle East, providing a hardier crop when it comes to global warming.

"They can't do it all in two years," he says. "We're now in a period of calm [following Brexit] where we can engage with universities and the higher education minister. There is the potential to bring the best and brightest people who are very well qualified, to the UK."

Charlie is a freelance journalist based in the Middle East. Her current work focuses on migration, economics, human rights, gender issues and culture, across the region.

Follow her on Twitter: @Charlie_Faulk