Welcome to Wadi al-Salam, the world's biggest graveyard

Welcome to Wadi al-Salam, the world's biggest graveyard

In-depth: A look inside the most profitable business in Iraq.

5 min read

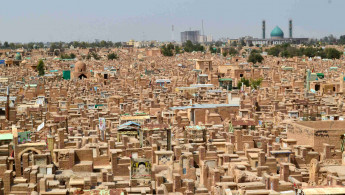

Tomb with a view: Wadi al-Salam is adjacent to Shia Islam's holiest shrine [Gareth Browne]

In the early 1980s, as Iraq entered into an eight-year war with Iran that would cost millions of lives, Maajid travelled to work with his ageing father.

More than 40 years later, with Iraq locked in the middle of another brutal war, he has taken over the family business, digging graves in the Wadi Al-Salam cemetery - believed to be the largest in the world.

Sprawling in the holy city of Najaf, and within sight of the shrine of Ali Ibn Abi Talib - the first of twelve Shia imams - and the pre-eminent Shia holy site. So holy is the shrine that the coffins of those set to be buried here are brought into the shrine for several laps of blessing before being taken for burial.

Wadi Al-Salam, or Valley of Peace, is probably the most highly desired final resting place of many Shia Muslims around the word. Mohammad Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr, father of firebrand cleric Moqtada Al-Sadr, and who formerly served as Grand Ayatollah before his assaination, is but one of the high-ranking clerics buried here.

Recent estimates put the number of those buried in Wadi Al-Salam at some five million, but the cemetery - active for 1,400 years - has seen unprecedented changes in recent times amid the battle against the Islamic State group.

The cemetery, which has borne witness to Iraq's tumultuous history, hosts more burials per day than ever before. As many as 350 people have been interred every day for the past several months - a result of the fierce fighting in Mosul and beyond.

"I'm burying more now than ever before, more than my father buried during the war against Iran, more than when the Americans came," says Maajid. He is torn with guilt, profiting as his countrymen die in record numbers.

"It's sad, while my country is at war, I live comfortably, and my children eat well."

So adept have Maajid and his colleagues become, they can have a grave ready for burial within three hours of it first being requested. According to Islamic law, Muslim bodies must be buried as soon as possible - usually on the same day as death, making Maajid's job all the more difficult.

The huge cemetery is already spread over almost 1,500 acres, but Shia authorities known as the Marja are already trying to buy up new land to the east of its current boundary. The rapidly shrinking free space has led to theft and the re-purposing of older burial sites as people desperately clamour to find space for their loved ones in Wadi Al-Salam.

The cheapest plot in Wadi Al-Salam can be yours for 350,000 Iraqi dinars, or around $300. The price increases nearly exponentially, however, with the addition of crypts or specialised headstones. The cemetery, once a panorama of subtly differing shades of clay brown, is now infused with bright posters memorialising those killed in the fighting.

The posters are replete with pictures of those referred to as shaheeds, or martyrs, often with a rifle in hand. Huddled groups of women clad in chadors have travelled from as far as Iran and Lebanon. They are herded along the dirt roads, pilgrims visiting not just Iraq's sacred Shia sites, but also the burial plots of loved ones. They are just a few of the millions who visit this cemetery each year.

"I sometimes wonder how the person I'm burying died," says Maajid. Many of those he has buried recently have been killed in Mosul. Their coffins arrive, often draped in the flags of militias or military units. "We know who the martyrs are, we know the ones who have died fighting IS."

So great has been the number of those killed in the fighting that some of the largest militias operating in Iraq - notably the Badr organisation and Kata'ib Hizballah - have opened burial offices in Najaf, and now fully manage the interment of the those killed fighting, whereas the Iraqi Army do not.

The militias organise and pay for everything the corpse requires, from the transportation of the fighter's body to the inscription on their tomb.

The cemetery was recently made a UNESCO world heritage site, but its swelling capacity is also a testament to the fact that even Iraq's oldest institutions are being challenged by the Islamic State group - in both its rise and fall.

With such demand for graves in Wadi Al-Salam, and indeed across Iraq, Maajid is already preparing his two sons to take over the family business. One is 13, the other 16, but they already help out on weekends and after school. Though he is reluctant to name them for fear of their safety - in Iraq, even burials can be interpreted as a political act - he is proud that they will inherit the operation:

"One day, they will manage the burial of hundreds," he says.

Gareth Browne is a freelance reporter based in Erbil. He has been reporting from the front lines in the battle to retake Mosul from the Islamic State group and recently visited Baghdad to study the legacy of the US-led invasion.

Follow him on Twitter: @BrowneGareth

More than 40 years later, with Iraq locked in the middle of another brutal war, he has taken over the family business, digging graves in the Wadi Al-Salam cemetery - believed to be the largest in the world.

Sprawling in the holy city of Najaf, and within sight of the shrine of Ali Ibn Abi Talib - the first of twelve Shia imams - and the pre-eminent Shia holy site. So holy is the shrine that the coffins of those set to be buried here are brought into the shrine for several laps of blessing before being taken for burial.

Wadi Al-Salam, or Valley of Peace, is probably the most highly desired final resting place of many Shia Muslims around the word. Mohammad Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr, father of firebrand cleric Moqtada Al-Sadr, and who formerly served as Grand Ayatollah before his assaination, is but one of the high-ranking clerics buried here.

|

I'm burying more now than ever before, more than my father buried during the war against Iran, more than when the Americans came |  |

Recent estimates put the number of those buried in Wadi Al-Salam at some five million, but the cemetery - active for 1,400 years - has seen unprecedented changes in recent times amid the battle against the Islamic State group.

The cemetery, which has borne witness to Iraq's tumultuous history, hosts more burials per day than ever before. As many as 350 people have been interred every day for the past several months - a result of the fierce fighting in Mosul and beyond.

"I'm burying more now than ever before, more than my father buried during the war against Iran, more than when the Americans came," says Maajid. He is torn with guilt, profiting as his countrymen die in record numbers.

"It's sad, while my country is at war, I live comfortably, and my children eat well."

|

| The tomb of a young boy killed in an Islamic State group attack. Even children killed by IS are referred to as 'martyrs' [Gareth Browne] |

So adept have Maajid and his colleagues become, they can have a grave ready for burial within three hours of it first being requested. According to Islamic law, Muslim bodies must be buried as soon as possible - usually on the same day as death, making Maajid's job all the more difficult.

The huge cemetery is already spread over almost 1,500 acres, but Shia authorities known as the Marja are already trying to buy up new land to the east of its current boundary. The rapidly shrinking free space has led to theft and the re-purposing of older burial sites as people desperately clamour to find space for their loved ones in Wadi Al-Salam.

The cheapest plot in Wadi Al-Salam can be yours for 350,000 Iraqi dinars, or around $300. The price increases nearly exponentially, however, with the addition of crypts or specialised headstones. The cemetery, once a panorama of subtly differing shades of clay brown, is now infused with bright posters memorialising those killed in the fighting.

|

We know who the martyrs are, we know the ones who have died fighting IS |  |

The posters are replete with pictures of those referred to as shaheeds, or martyrs, often with a rifle in hand. Huddled groups of women clad in chadors have travelled from as far as Iran and Lebanon. They are herded along the dirt roads, pilgrims visiting not just Iraq's sacred Shia sites, but also the burial plots of loved ones. They are just a few of the millions who visit this cemetery each year.

"I sometimes wonder how the person I'm burying died," says Maajid. Many of those he has buried recently have been killed in Mosul. Their coffins arrive, often draped in the flags of militias or military units. "We know who the martyrs are, we know the ones who have died fighting IS."

|

| A team of gravediggers drive past the often gaudy memorials to those laying at rest in Wadi al-Salam, Iraq's Valley of Peace [Gareth Browne] |

So great has been the number of those killed in the fighting that some of the largest militias operating in Iraq - notably the Badr organisation and Kata'ib Hizballah - have opened burial offices in Najaf, and now fully manage the interment of the those killed fighting, whereas the Iraqi Army do not.

The militias organise and pay for everything the corpse requires, from the transportation of the fighter's body to the inscription on their tomb.

The cemetery was recently made a UNESCO world heritage site, but its swelling capacity is also a testament to the fact that even Iraq's oldest institutions are being challenged by the Islamic State group - in both its rise and fall.

With such demand for graves in Wadi Al-Salam, and indeed across Iraq, Maajid is already preparing his two sons to take over the family business. One is 13, the other 16, but they already help out on weekends and after school. Though he is reluctant to name them for fear of their safety - in Iraq, even burials can be interpreted as a political act - he is proud that they will inherit the operation:

"One day, they will manage the burial of hundreds," he says.

Gareth Browne is a freelance reporter based in Erbil. He has been reporting from the front lines in the battle to retake Mosul from the Islamic State group and recently visited Baghdad to study the legacy of the US-led invasion.

Follow him on Twitter: @BrowneGareth