Yemen's quiet secession

Yemen's quiet secession

As turmoil engulfs Yemen, the secessionist ambitions of the South received a boost from an unlikely source, President Hadi himself, says Faris al-Jalal.

5 min read

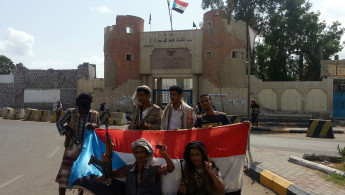

Southern authorities are refusing orders from Houthi-controlled Sanaa [AFP]

If you do not know the conditions that led to Yemen's 1994 civil war between the north and the south, one that came only four years after the unification of the formerly independent states of North and South Yemen, then you may look at current events and focus on the resignation of the president, Abd-Rabbo Mansour Hadi, and the government of prime minister Khalid Bahah, and what is essentially an undeclared secession that has already taken place in the southern provinces of Aden and Hadhramaut.

You may focus on the warning signs of a north-south war, after armed clashes took place in Aden and southern 'Popular Committees' took control of southern cities, as well as the return of southerners residing in Sanaa and other northern areas to the south.

However, those who lived those years will know that the situation today is very similar to 1994, with some differences, such as the president, and the presence of the Houthis in Sanaa.

In 1994, the president was Ali Abdullah Saleh, and his vice-president was Ali Salem al-Beidh, a southerner. Now, the president, at least until his resignation is accepted, is Hadi, and he has no deputy. In 1994, Saleh's allies were the Islah Party and the tribes, as well as some religious groups, such as returning mujahideen from Afghanistan. Saleh used these groups to attack the Socialists and the South as a whole. Interestingly enough, the Houthis, before they became an established movement, rejected the war.

Southerners "united" for secession

Today, Islah is distancing itself, and it is the Houthis who are facing off against the southerners, along with the Saleh-wing of the General People's Congress. The Houthis have taken Islah's previous role in “defending” Yemeni unity.

Southern politicians and leaders now say that the rhetoric today is the same as it was in 1994. According to them, the methods are that of one man – Saleh. The expectation, therefore, is that a new war will be fought against the south, but this time things may be different.

In 1994, the south was divided between those who supported unity and those who wanted to separate. That has changed, and now the idea that secession is a necessity enjoys mass support, with it being described as a “life or death” issue.

Hadi's men are dominant in the south, and they are leading a subtle move to secede. This is being done with the use of the popular committees, as well as southern army and security units following orders from the leadership of the security committee in Aden. At the same time, they are attempting to neutralise the army and security units stationed in the south that still follow orders from the Houthis and Saleh, by being clear that their actions are in support of constitutional legitimacy and in opposition to the coup.

In this, they are being supported by factions of the secessionist Herak movement, as well as parties, political and tribal figures, and civil society groups in the south.

Popular committees have been formed across the southern provinces, and hundreds of armed men have appeared, including in Aden, which is under the control of popular committees who have arrived from Abyan and Lahj. This coincides with the return of a number of second tier southern officials from the north, after top southern officials were held under house arrest in Sanaa.

The popular and tribal committees in the areas around the former border between north and south have begun to not allow entry for any vehicle carrying a northern number plate, forcing the passengers to cross the former border by foot. On Thursday night, Mansoura, in Aden, saw explosions and clashes after armed men from the town attacked the barracks of the Special Forces, formerly known as the Central Security Forces, that has been situated in Martyr's Square over the past few months. The armed men were able to seize the barracks early on Friday after the troops inside fled. At the same time, the flag of the former South Yemen began to appear on various government installations, for the first time since unity in 1990.

The decisions by the authorities in the south have received wide backing, especially as southerners, including those who supported unity, have reached the conclusion that their former state must return. Some even say that what has happened to southerners over the past two years, culminating in the targeting of Hadi, is worse than what happened in 1994. They say that the targeting now is almost sectarian.

Secession looks irreversible

Southerners have taken to the streets to demonstrate, and to support the decisions undertaken by the army command in Aden. They now feel that this may finally be the beginning of the eventual victory of their cause.

Although some are doubtful, there is a growing opinion that the de facto secession that has occurred cannot be reversed.

This belief is strengthened by the call by dozens of southern leaders, including former president Haidar Abubakr al-Attas, for the secession of the southern provinces as soon as Hadi resigned. Attas is known to be close to regional countries, including Saudi Arabia. This has made observers wonder if the moves had been pre-planned, and with foreign support.

In the past few months, in the wake of the Houthi takeover of Sanaa and the possibility of continued conflict in the north, foreign powers have been waiting for southern leaders to set aside their differences and unite. This appears to have happened, now that they have agreed on the principle of an end to unity.

“There is sympathy from the countries in the region, and internationally, for the southern issue, in light of the chaos [that is occuring] and the fear of the Houthi project, that is linked to Tehran,” said Fadhl Mubarak, a political analyst.

“Recent events have created a realignment in the south... Hadi was seen [previously] as the president of an occupying country – [now] there is some sort of cooperation between the authorities in the southern provinces and Herak factions,” Mubarak added.

For Mubarak, the possibility of Herak being able to achieve their goal of a southern state, is very real. And that would mean the end of a united Yemen.

You may focus on the warning signs of a north-south war, after armed clashes took place in Aden and southern 'Popular Committees' took control of southern cities, as well as the return of southerners residing in Sanaa and other northern areas to the south.

However, those who lived those years will know that the situation today is very similar to 1994, with some differences, such as the president, and the presence of the Houthis in Sanaa.

In 1994, the president was Ali Abdullah Saleh, and his vice-president was Ali Salem al-Beidh, a southerner. Now, the president, at least until his resignation is accepted, is Hadi, and he has no deputy. In 1994, Saleh's allies were the Islah Party and the tribes, as well as some religious groups, such as returning mujahideen from Afghanistan. Saleh used these groups to attack the Socialists and the South as a whole. Interestingly enough, the Houthis, before they became an established movement, rejected the war.

Southerners "united" for secession

Today, Islah is distancing itself, and it is the Houthis who are facing off against the southerners, along with the Saleh-wing of the General People's Congress. The Houthis have taken Islah's previous role in “defending” Yemeni unity.

Southern politicians and leaders now say that the rhetoric today is the same as it was in 1994. According to them, the methods are that of one man – Saleh. The expectation, therefore, is that a new war will be fought against the south, but this time things may be different.

In 1994, the south was divided between those who supported unity and those who wanted to separate. That has changed, and now the idea that secession is a necessity enjoys mass support, with it being described as a “life or death” issue.

Hadi's men are dominant in the south, and they are leading a subtle move to secede. This is being done with the use of the popular committees, as well as southern army and security units following orders from the leadership of the security committee in Aden. At the same time, they are attempting to neutralise the army and security units stationed in the south that still follow orders from the Houthis and Saleh, by being clear that their actions are in support of constitutional legitimacy and in opposition to the coup.

In this, they are being supported by factions of the secessionist Herak movement, as well as parties, political and tribal figures, and civil society groups in the south.

Popular committees have been formed across the southern provinces, and hundreds of armed men have appeared, including in Aden, which is under the control of popular committees who have arrived from Abyan and Lahj. This coincides with the return of a number of second tier southern officials from the north, after top southern officials were held under house arrest in Sanaa.

The popular and tribal committees in the areas around the former border between north and south have begun to not allow entry for any vehicle carrying a northern number plate, forcing the passengers to cross the former border by foot. On Thursday night, Mansoura, in Aden, saw explosions and clashes after armed men from the town attacked the barracks of the Special Forces, formerly known as the Central Security Forces, that has been situated in Martyr's Square over the past few months. The armed men were able to seize the barracks early on Friday after the troops inside fled. At the same time, the flag of the former South Yemen began to appear on various government installations, for the first time since unity in 1990.

The decisions by the authorities in the south have received wide backing, especially as southerners, including those who supported unity, have reached the conclusion that their former state must return. Some even say that what has happened to southerners over the past two years, culminating in the targeting of Hadi, is worse than what happened in 1994. They say that the targeting now is almost sectarian.

Secession looks irreversible

Southerners have taken to the streets to demonstrate, and to support the decisions undertaken by the army command in Aden. They now feel that this may finally be the beginning of the eventual victory of their cause.

Although some are doubtful, there is a growing opinion that the de facto secession that has occurred cannot be reversed.

This belief is strengthened by the call by dozens of southern leaders, including former president Haidar Abubakr al-Attas, for the secession of the southern provinces as soon as Hadi resigned. Attas is known to be close to regional countries, including Saudi Arabia. This has made observers wonder if the moves had been pre-planned, and with foreign support.

In the past few months, in the wake of the Houthi takeover of Sanaa and the possibility of continued conflict in the north, foreign powers have been waiting for southern leaders to set aside their differences and unite. This appears to have happened, now that they have agreed on the principle of an end to unity.

“There is sympathy from the countries in the region, and internationally, for the southern issue, in light of the chaos [that is occuring] and the fear of the Houthi project, that is linked to Tehran,” said Fadhl Mubarak, a political analyst.

“Recent events have created a realignment in the south... Hadi was seen [previously] as the president of an occupying country – [now] there is some sort of cooperation between the authorities in the southern provinces and Herak factions,” Mubarak added.

For Mubarak, the possibility of Herak being able to achieve their goal of a southern state, is very real. And that would mean the end of a united Yemen.