The inverse Libyan migrant issue

The inverse Libyan migrant issue

Comment: The emphasis on the impact of immigration on Europe for the future has diverted focus from the impact on Libya for the present, says Sophia Akram.

5 min read

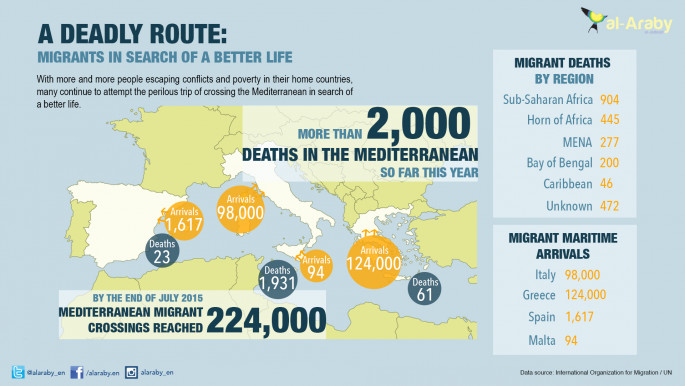

Thousands have died trying to cross the Mediterranean to Europe this year [Getty]

Libya is regularly making headlines these days for its influx of migrants coming towards Europe.

The desperate rallying on policy and now tactical responses to this problem is because immigration is a political hot potato that's looking at all options rather than embracing humanitarian principles of asylum and human rights obligations of non-refoulement.

This emphasis on the impact on Europe for the future has diverted focus from the impact on Libya for the present.

Migration flows

Libya is a country of origin, destination and transit for irregular migration, although actual figures of the inflows and outflows are highly speculative.

Since the uprising of 2011 and then the crisis of 2014, Libyan nationals have fled the country.

However, it has also attracted migrants from Arab, sub-Saharan African countries and Asian countries that include those fleeing from persecution as well as economic migrants.

For some, their intention is to move on to Europe; others have been in Libya for a long time as Gadhafi’s regime readily encouraged foreign labour in the 1980s and 1990s. However, this eventually turned into a significant irregular migration issue and started initiating internal problems.

Unemployment

Unemployment is one of the major issues that face Libya, partly due to the nationalisation programme under Gadhafi.

According to a 2014 report by the European Training Foundation, the result was an overwhelmingly large public sector and under-developed private sector.

The expectations amongst many Libyans, especially graduates, were to be able to slot in to one of these positions but the state’s education system had not geared them towards being fully qualified for roles within these sectors and there was more reliance on expatriate workers to fill them.

Unwilling to fill the low wage and unskilled labour roles left, these again were sought out from foreign workers, while creating a large unemployment problem amongst Libyan nationals as the state failed to create jobs.

Labour shortages and infrastructure collapse

Since Libya has been embroiled by political instability, unemployment levels remain but due to the high migration flows out of the country there are severe labour shortages, including in the high skills areas jeopardising the development and infrastructure of the country.

“Since 2011, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers have fled Libya, leaving vast gaps in the local labour market – including in sectors critical to ensure that essential services, such as health care, remain available throughout the country“ a representative from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) stated.

Inability to tackle trafficking

Amnesty International recently reported on the horrendous treatment of migrants by human traffickers as they are taken across deserts from the southwest border in order to reach the "death boats" towards the Mediterranean.

While the EU deliberate on blowing up the death vessels, a little more nuanced understanding will illuminate the emergence of this route.

Rebecca Murray recently reported in the McClatchy DC that the traffickers tend to be indigenous Tebu, Tuareg and local Arabs, depending on the region and who are familiar with the hostile terrain of the Libyan desert.

They suffered state-sanctioned discrimination under Gadhafi and thus learned the illicit trade in people when there were no other opportunities and those that served in Gadhafi’s army had no central authority after his demise.

The Libyan state, amongst its political split is wanton of any means to fight the traffickers now as border security has its hands full with the drug trade and terrorists.

Migrants, it seems are not their foremost priority.

That’s why the East’s Tobruk-based government has asked for its four-year arms embargo to be lifted.

More guns may help combat traffickers before they get to the coastlines in addition to more resources and equipment such as vehicles.

But the UN recently refused the request for fear the shipments go into the wrong hands.

Remittances back home stop

According to IOM’s Maysa Khalil, “Libyan officials acknowledge that irregular migrants often seek employment, either to continue their journey to Europe, to send remittances back to their origin countries, or to gather enough savings to return to them.”

Libya’s role in development terms for those from less prosperous countries has therefore, diminished significantly. Being sent back from Europe, will mean they will revert back to joining the ranks of un and underemployed, compounding the pressures already felt on their countries.

The interventions

An EU project called the START programme, which is being implemented by the IOM, is one way in which these challenges are trying to be overcome.

After the 2011 uprisings, it was recognised that in Libya (and not just Libya, Egypt and Tunisia) that there would be tumultuous migratory surges that would need to be managed.

With Libya’s track record of handling migration, it was recognised that some work had to be done with the Ministry of Labour and border officials to establish the pre-conditions necessary for smooth transitions and comprehensive and sustainable recoveries in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia.

Many of its activities are around capacity building and teaching the Government how to address labour market gaps, manage migration flows and stabilise at-risk communities that typically experience unemployment and direct assistance to irregular migrants.

While the high-level goals of the programme are admirable, the instability has prevented a full rollout of initiatives and activities have mostly focused on direct assistance i.e. distribution of non-food items to refugees and displaced and access to health services as well as some assessment activities.

In addition, deportations and return and repatriation activities are also taking place.

By 2014, Italy was receiving 80 percent of the flows across the Mediterranean.

Today the EU nations are literally in a panic and some potentially adverse policy and tactical activities are being proposed.

Europe’s defensive intervention against smugglers is unwelcome by Libya and Da’esh (Islamic State group) is posing an ever increasing threat in addition to the current conflict dynamics, which is not likely to see the North African nation stabilised any time soon.

However, this has also not deterred migrants using Libya as a transit point, therefore, the pull factors of Europe are not as relevant as the push factors from their own countries requiring more social inclusion and labour initiatives as well as increased capacity for security personnel.

While UK Defence Secretary, Michael Fallon, did state that addressing the root cause of the problem is more important than the symptoms, the problem for the EU is unfortunately migrants in Europe, rather than lack of opportunities and security of migrants; and not least the detrimental affects it is having on Libya itself.

The desperate rallying on policy and now tactical responses to this problem is because immigration is a political hot potato that's looking at all options rather than embracing humanitarian principles of asylum and human rights obligations of non-refoulement.

This emphasis on the impact on Europe for the future has diverted focus from the impact on Libya for the present.

Migration flows

Libya is a country of origin, destination and transit for irregular migration, although actual figures of the inflows and outflows are highly speculative.

Since the uprising of 2011 and then the crisis of 2014, Libyan nationals have fled the country.

However, it has also attracted migrants from Arab, sub-Saharan African countries and Asian countries that include those fleeing from persecution as well as economic migrants.

For some, their intention is to move on to Europe; others have been in Libya for a long time as Gadhafi’s regime readily encouraged foreign labour in the 1980s and 1990s. However, this eventually turned into a significant irregular migration issue and started initiating internal problems.

Unemployment

Unemployment is one of the major issues that face Libya, partly due to the nationalisation programme under Gadhafi.

According to a 2014 report by the European Training Foundation, the result was an overwhelmingly large public sector and under-developed private sector.

The expectations amongst many Libyans, especially graduates, were to be able to slot in to one of these positions but the state’s education system had not geared them towards being fully qualified for roles within these sectors and there was more reliance on expatriate workers to fill them.

Unwilling to fill the low wage and unskilled labour roles left, these again were sought out from foreign workers, while creating a large unemployment problem amongst Libyan nationals as the state failed to create jobs.

Labour shortages and infrastructure collapse

Since Libya has been embroiled by political instability, unemployment levels remain but due to the high migration flows out of the country there are severe labour shortages, including in the high skills areas jeopardising the development and infrastructure of the country.

“Since 2011, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers have fled Libya, leaving vast gaps in the local labour market – including in sectors critical to ensure that essential services, such as health care, remain available throughout the country“ a representative from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) stated.

Inability to tackle trafficking

Amnesty International recently reported on the horrendous treatment of migrants by human traffickers as they are taken across deserts from the southwest border in order to reach the "death boats" towards the Mediterranean.

While the EU deliberate on blowing up the death vessels, a little more nuanced understanding will illuminate the emergence of this route.

Rebecca Murray recently reported in the McClatchy DC that the traffickers tend to be indigenous Tebu, Tuareg and local Arabs, depending on the region and who are familiar with the hostile terrain of the Libyan desert.

They suffered state-sanctioned discrimination under Gadhafi and thus learned the illicit trade in people when there were no other opportunities and those that served in Gadhafi’s army had no central authority after his demise.

The Libyan state, amongst its political split is wanton of any means to fight the traffickers now as border security has its hands full with the drug trade and terrorists.

Migrants, it seems are not their foremost priority.

That’s why the East’s Tobruk-based government has asked for its four-year arms embargo to be lifted.

More guns may help combat traffickers before they get to the coastlines in addition to more resources and equipment such as vehicles.

But the UN recently refused the request for fear the shipments go into the wrong hands.

Remittances back home stop

According to IOM’s Maysa Khalil, “Libyan officials acknowledge that irregular migrants often seek employment, either to continue their journey to Europe, to send remittances back to their origin countries, or to gather enough savings to return to them.”

Libya’s role in development terms for those from less prosperous countries has therefore, diminished significantly. Being sent back from Europe, will mean they will revert back to joining the ranks of un and underemployed, compounding the pressures already felt on their countries.

The interventions

An EU project called the START programme, which is being implemented by the IOM, is one way in which these challenges are trying to be overcome.

After the 2011 uprisings, it was recognised that in Libya (and not just Libya, Egypt and Tunisia) that there would be tumultuous migratory surges that would need to be managed.

With Libya’s track record of handling migration, it was recognised that some work had to be done with the Ministry of Labour and border officials to establish the pre-conditions necessary for smooth transitions and comprehensive and sustainable recoveries in Libya, Egypt and Tunisia.

Many of its activities are around capacity building and teaching the Government how to address labour market gaps, manage migration flows and stabilise at-risk communities that typically experience unemployment and direct assistance to irregular migrants.

While the high-level goals of the programme are admirable, the instability has prevented a full rollout of initiatives and activities have mostly focused on direct assistance i.e. distribution of non-food items to refugees and displaced and access to health services as well as some assessment activities.

In addition, deportations and return and repatriation activities are also taking place.

By 2014, Italy was receiving 80 percent of the flows across the Mediterranean.

Today the EU nations are literally in a panic and some potentially adverse policy and tactical activities are being proposed.

Europe’s defensive intervention against smugglers is unwelcome by Libya and Da’esh (Islamic State group) is posing an ever increasing threat in addition to the current conflict dynamics, which is not likely to see the North African nation stabilised any time soon.

However, this has also not deterred migrants using Libya as a transit point, therefore, the pull factors of Europe are not as relevant as the push factors from their own countries requiring more social inclusion and labour initiatives as well as increased capacity for security personnel.

While UK Defence Secretary, Michael Fallon, did state that addressing the root cause of the problem is more important than the symptoms, the problem for the EU is unfortunately migrants in Europe, rather than lack of opportunities and security of migrants; and not least the detrimental affects it is having on Libya itself.

|

|

![Migrants arrive at the Greek island of Kos [Getty] Migrants arrive at the Greek island of Kos [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/media/images/C105078A-5F61-4A3E-84D1-902F9CFE0C1E.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=qKqb1dHr)