Post-Brexit: More UK arms sales to the Middle East?

With no special deal in the offing for the UK over access to the common market, British jobs and industry are likely to go through a period of severe uncertainty. The removal of EU regulations provides the British arms industry with the opportunity to infiltrate developing countries with poor human rights records, to secure threatened British jobs and foreign investment. Moreover, the UK's position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council will be blunted by their exit of the EU.

The EU has considerable diplomatic and economic power globally, and has exercised this in the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region, from counter-terror coordination with Tunisia, to building nascent Palestinian Authority institutions, to implementing sanctions on Iran. Brexit means the UK will need to achieve its interests in the region through different means, which is likely to result in arms contracts as a way to maintain its eroding diplomatic clout.

The UK arms industry is a vital component of the UK economy. Campaign Against Arms Trade data suggests that there are around 170,000 UK arms industry jobs, with 115,000 related to the UK Ministry of Defence and a further 55,000 related to exports. The value of the global defence export market was estimated at more than $50 billion in 2014 according to the UK's trade and investment data.

This makes the UK the world's second largest arms exporter in that year, behind the United States. The UK's heavy weight companies include Babcock, Serco, Cobham, QuinetiQ, GKN and Meggit, all in the top 100 arms companies in the world. The heavy weight title goes to BAE systems, coming out as the world's third largest seller of weapons, netting $US25.7 billion last year. BAE Systems has approximately 34,800 employees based in around 50 sites across the UK.

|

British made aircraft and their payload have been used to devastating effect by Saudi Arabia in its war against Houthi rebels in Yemen |  |

|

| Click to enlarge |

A month prior to publication of the data, BAE Systems reorganised its interests in Saudi Arabia into one entity to enhance its relationship with is partner in the kingdom, Riyadh Wings. This move consolidated the al-Yamamah arms deal between the UK and Saudi Arabia. Over the next two years 72 Typhoon aircraft were delivered to Saudi Arabia, in a deal with roots in the Thatcher administration between 1979-1991.

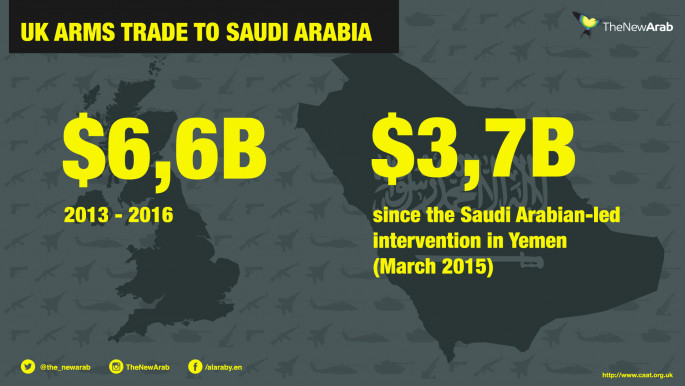

The British government has licensed exports worth £6.8 billion since David Cameron was elected in 2010, including munitions for previously supplied aircraft such as brimstone and storm-shadow air-to-surface guided bombs. British made aircraft and their payload have been used to devastating effect by Saudi Arabia in its war against Houthi rebels in Yemen. In this war civilians have been caught up in the violence with 2,682 killed according to a leaked UN report in January this year.

At a hearing at the High Court in London last week, Mr Justice Gilbart gave permission for a judicial review into whether arms sales to Saudi breach domestic and EU laws. Indeed, the UK arms industry is regulated largely by EU regulations.

The 1998 European Union Code of Conduct on Arms Exports includes human rights provisions on the sales of any arms to countries. This was reinforced by the 2008 Common Position, which replaced the code of conduct introducing more measures for greater transparency and stricter provisions on sales to countries engaged in regional instability. In 2013 the UN adopted the Arms Trade Treaty, and the EU in turn adopted a dedicated support programme to reinforce the implementation of this treaty.

The UK's position on the international stage has been waning for decades, and economic downturn in the 1970s was accompanied with a pivot away from manufacturing industry to financial services.

This shift played a significant role in a deregulated banking sector which defaulted in 2008, with the British economy dipping into a deep recession. The arms industry was one of the only sectors to emerge largely unscathed.

|

As American academic Noam Chomsky notes, Brexit is likely to keep the UK more accountable to US power |  |

The Iraq war demonstrated how accountable to the US the UK has become, with the symbolic commitment of antiquated British aircraft in the fight against IS in Syria sounding the death rattle of British hard power on the international stage. Trade visits to China and India by outgoing Prime Minister David Cameron were often conducted from a position of weakness.

The EU played a small role in tempering the gravitational hold Washington has played over London, and as American academic Noam Chomsky notes, Brexit is likely to keep the UK more accountable to US power. With regards to the MENA region, Washington is looking to remove itself, and in this vacuum Washington's regional allies are set to fill the void the US will leave behind.

Operation Northern Thunder in Saudi Arabia - the largest joint military operation in the region to date - is an indication of how many Sunni Gulf states view the coming years. For the UK, an increasingly assertive Saudi-led Sunni bloc, keen to stem a perceived resurgent Iran, presents them with opportunities to increase arms sales and gain political traction in a region in transition.

Brexit not only removes the legal safeguards to unfettered flow of arms, but the political and economic realities may compel London to sign more contracts with regimes engaged in an arms race with their regional rivals.

Nick Rodrigo is a freelance researcher working for the Afro-Middle East Centre based in Johannesburg. He holds an MA in the Theory and Practice of Human Rights from the University of Essex, and has previously worked with Iranian and Palestinian human rights organisations.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.