For Palestinians, elections won't challenge the rule of Israel's 'domination' camp

While it looks like Netanyahu's coalition will remain intact - at least for now - the longevity of his razor-thin coalition is far from guaranteed. Predicting election results is a notoriously ambitious task, and all the more so in a country such as Israel, with its own perplexing electoral system.

In some ways, voting for the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, is simpler than casting ballots in many other countries. In part because the country is so small (even when counting all of the occupied territories), it hardly makes sense to use a district system where MPs represent their local ridings.

Instead, voting-age Israeli citizens pick their preferred political party, and as long as that party earns at least 3.25 percent of all votes cast, they send their proportion of MPs to the national legislature.

Since parties with only a modicum of popular support are not weeded out of the running in first-past-the-post local races as in other countries, the 120-seat parliament has always been composed of multiple factions, far more than in the two-or-three-party systems that most westerners are accustomed to.

This voting format ensures that a wide range of views are represented in the Knesset, but it can also make it complicated for the leader of the largest party to form a majority government.

With dozens of parties running for parliament, it's much more difficult for foreigners - especially those who don't understand modern Hebrew - to make head or tail of the Israeli political spectrum. Making matters more complicated, the parties' fortunes fluctuate erratically from election to election, shifting the balance of power every few years, and making it difficult to predict poll results with any certainty.

Israel has four political camps

In other countries, political factions are often graded on a linear scale of left to right, representing the parties' perspectives on economic issues.

Naturally, financial issues are also of great importance in Israel, but these are superseded by security concerns, issues of war and peace. On this issue, the parties can be assigned to one of four different political camps, based on how they would prefer to treat Palestinians in the long run: Segregation, Integration, Domination and Elimination.

|

Only a quarter of Israeli Jews say they want the single state that remains to be a democratic one |  |

The "Segregation" (or "Separation") camp wants a two-state solution: A Jewish State of Israel and a Palestinian state alongside it.

The "Integration" camp wants one democratic state stretching from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

The "Domination" camp also wants a one-state solution for all of historic Palestine, but one in which Jews have more rights than non-Jews, and in which they dominate Palestinians.

And the Elimination camp wants that one-state to ultimately be ethnically cleansed of Palestinians and other non-Jews.

All Israeli political parties can be lumped into one of these four camps, or sides, and their names can be easily recalled using the acronym formed from the first letter of each of the camps: SIDE.

|

|

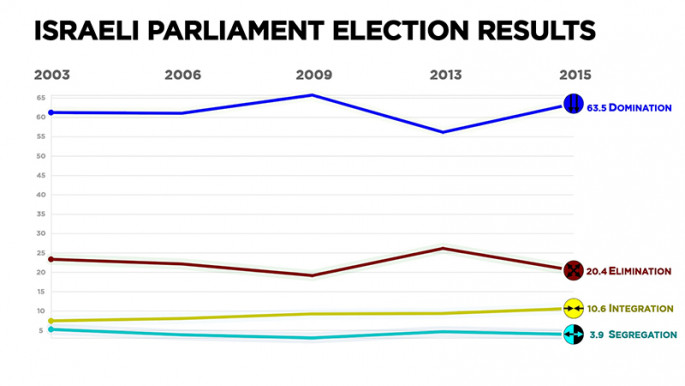

| Regardless of which parties won Israeli elections, those in favour of 'Domination' over Palestinians have remained on top [David Sheen] |

A year ago in December 2017, a team from Tel Aviv University polled Israeli Jews on the endgame scenario they would prefer to play out vis-a-vis the Palestinians.

The stated results were as follows: 45 percent preferred the Segregation solution, 14 percent preferred Integration, 11 percent preferred Domination, and 14 percent preferred Elimination.

On the face of it, the poll results would seem to be encouraging. They indicate that a significant majority of Israeli Jews would prefer that the country consist of either one or two democratic states, and those who want apartheid or worse add up to a quarter of the Jewish population - a troubling figure, to be sure, but still only a minority.

When one reads the poll's fine print, however, things get much murkier.

|

Israeli Jews have a tendency to exaggerate their support for democracy, and to under-report their support for apartheid or even worse |  |

Close to half of the Jewish respondents professed to support a two-state solution for Israel-Palestine, but when probed further on the specific details that any actual two-state solution would entail, this wide base of support quickly dissolved.

Quizzed about security control, settlement evacuation, territory swaps, a capital in Jerusalem, and refugees' right of return - the absolute minimum conditions necessary for any such solution, as far as Palestinians are concerned - Jewish support for two states plummeted to less than 19 percent.

Furthermore, when the two-state solution is taken off the table as a possible option - and truth be told, Israeli obstructionism and settlement expansion has likely made any such solution impossible to implement - only a quarter of Israeli Jews say they want the single state that remains to be a democratic one.

|

|

| Election results since 2003 appear varied, but many of the winning parties hold similar policies when it comes to 'security' and the question of the occupied Palestinian territories [David Sheen] |

More than 60 percent of the Jewish population say they want that one remaining state to be one in which Arabs are only second-class at best, or else expelled altogether.

It would seem that Israeli Jews have a tendency to exaggerate their support for democracy, and to under-report their support for apartheid or even worse.

Rather than quizzing Israeli Jews on the number of states they would like to live in, a more reliable indicator of their political opinions would ask them how they would like the country's non-Jews to be treated, as in a Pew poll published in 2016.

The results: a full 79 percent embraced the Domination credo, which gives Jews preferential treatment over Palestinians, and 48 percent embraced the Elimination credo, which would see Palestinian citizens of Israeli expelled from the land altogether.

This frightening portrait of Israeli society is confirmed by my independent analysis of the results of the 2003, 2006, 2009, 2013 and 2015 elections for Knesset - all the national polls held since the start of the millennium - by political camp, instead of by political party.

|

The 2019 elections are expected to produce more of the same |  |

The Israeli political system may appear to be a puzzling mess from afar, and even more so from up close. But when one zooms out to medium resolution, it becomes possible to see the forest for the trees, so to speak. And upon inspection at this level of detail, the Israeli political spectrum would appear to be very stable, indeed.

Since the start of the Second Intifada in 2000, every Israeli election has produced near-identical results: the Domination camp leads with about 60 percent of the popular vote, followed by the Elimination camp, with about 20 percent of the popular vote.

In third place, the Integration camp trails with about 10 percent of the popular vote, and in last place is the Segregation camp, with no more than 5 percent of the popular vote.

Read more: For racist Israel, Ethiopian Jews are 'ruining the Zionist dream'

Analysing the vote by locality turns up similarly skewed ratios. Between elections, some voters shift their loyalties from one party to another, but only rarely from one camp to another.

The Domination camp consistently wins in between 700 to 800 municipalities, the Elimination camp wins in between 150 and 200 municipalities, and the Integration camp wins in about 100 municipalities. The Segregation camp's take dropped from around 50 towns in 2003 to just one little village in the 2015 elections.

Barring any last-minute earth-shattering changes in the Middle East, the 2019 elections are expected to produce more of the same.

Whether elections are called early, or whether they are held at the latest possible date - a full year from now in November - they are highly unlikely to produce results that are significantly different from the current composition of the Knesset.

With a consecutive decade as Israeli prime minister under his belt, Benjamin Netanyahu will in all probability go on to win a fifth term, and then use that mandate to assemble yet another coalition government from the camps whose agendas he aims to advance: Domination and Elimination.

The future for Palestinians and other non-Jews in the territories under Israeli control continues to look exceedingly grim.

David Sheen is an independent journalist originally from Toronto, Canada and now based in Dimona, Israel.

Follow him on Twitter: @davidsheen

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.