Libya's sovereign wealth scandal: Taxpayers' billions squandered through nepotism, incompetence and wild gambling

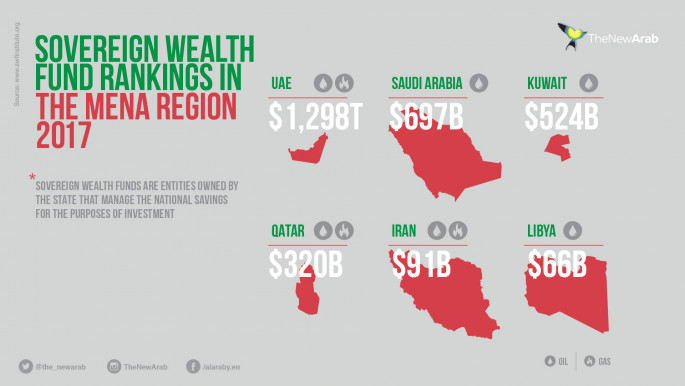

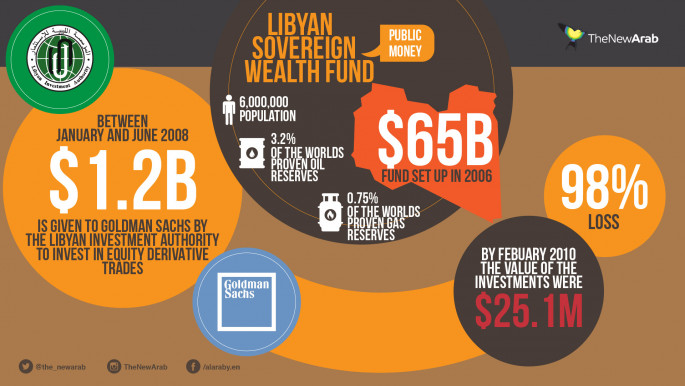

In 2006, just as sanctions imposed by Europe and the US on Libya were gradually lifted, but before Libya started selling any of its oil on the global markets, it was announced that Libya was to have its very own sovereign wealth fund: the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA).

It was, as an idea, worthy. Libya would invest for a post-oil future from the surplus it would accumulate from selling its crude overseas. With a population of just over six million sitting on nearly 3.2 percent of the world's proven oil reserves and 0.75 percent of its proven gas reserves, it was an equation likely to trigger the envy of most chancellors around the world.

LIA's funds quickly ballooned to reach an estimated $65 billion, prorated across three arms. Initially, an injection of more than $30 billion in cash was made available to LIA to be invested in bonds, hedge funds, and alternatives. Huge cash deposits were also maintained with the Central Bank of Libya and the Libya Foreign Bank. These two investment arms would soon account for nearly 60 percent of LIA's value.

Alongside this, LIA became an umbrella institution under whose auspices were placed companies set up by the Libyan state in the 1980s and 1990s, in sectors ranging from real-estate to hotels and hospitality, telecommunications to manufacturing. Scattered across the globe, though denser in Africa and Europe, much about these companies lies in obscurity.

The number thrown around by every executive to head LIA so far is 550 subsidiary companies. There is no formal documentation to back this up. There is no actual list.

In fact, LIA has not been audited since 2012 - and the last two CEOs to attempt an audit were both removed from their positions within 14 months of their appointment.

|

|

| The LIA is said to have been the brainchild of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi [AFP] |

Unbridled nepotism

It was, and there is consensus on this point, the brainchild of Seif el-Islam al-Gaddafi, the aspirational son of the now-deceased dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

He was at the time a frequenter of European capitals, pursuing intemperance in a manner available only to those with bank accounts of a certain plumpness.

His lavish spending was greeted in the west with eager accolades of his leadership qualities, all prospective of course. He was Libya's promise, its surest future, the moderniser who would transform Libya from pariah state into engaged 21st century actor. Or, in other words: he would liberalise and privatise its economy, opening up vast wealth to corporate tycoons and shareholders.

The London School of Economics accepted grants from a foundation he established and headed. It also awarded him a PhD. LIA, when he created it, was a token of the kind of future politics he espoused.

One of the first appointments to LIA was Mustafa Zarti, a close friend of the young Gaddafi from their student days in Austria.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

A source who spoke anonymously described him as Gaddafi's "drinking buddy".

Zarti had no significant nor relevant experience, but was made deputy head of LIA.

Ali Baruni, who has decades of experience behind him, worked as a consultant for LIA from its earliest days. What does he think of Zarti?

"Incompetent," he said. "He doesn't have the attention span, or the intellect. And when you make him manager of a $65 billion asset operation…" His words peter out.

Suffice to say, things were run a little differently than in other sovereign wealth funds.

First, there was no asset allocation strategy, so investment decisions did not follow anything resembling a plan. The sole directive pursued by the managers seems to have been to invest as much money as possible as quickly as possible.

Second, a sort of ritual was established whereby Gaddafi Jr and Zarti would meet with executives of investment banks and hedge funds. A few months later, an investment by LIA would be made. Case in point: in July 2007, aboard Gaddafi's yacht in Cannes, he and Zarti met with Driss Ben-Brahim, a Goldman Sachs partner. Investments by LIA soon followed: a total of eleven trades all signed within the space of seven months.

Baruni submitted his resignation after LIA's management went ahead with a Goldman Sachs deal he adamantly opposed. Ironically, this was one of two trades out of the eleven that went on to make some money. But shortly after his resignation, LIA signed the other nine deals in quick succession. The nine went on to fail, losing LIA its $1.2 billion investment.

| Investigative journalist Dr Deena Dajani and Ikbel Tlili co-produced an Al-Araby TV documentary on Libya's sovereign welath fund. Watch it here. [Arabic] |

Baruni firmly places the blame both ways: incompetent managers with unrealistic expectations of vast returns, and investment banks willing to tell these managers what they wanted to hear.

A realistic target for returns would have been between six and eight percent annually. "But for people who have no background in this, six percent is meaningless. They don't even think it is a good target or something to aim for. That was the fundamental problem. On the other hand, bankers... and others came with derivatives deals, one deal, and they say 'ok this thing will bring you 20 percent'.

"Of course, that generates a lot of excitement - and that is what happened.

"And of course, it wasn't 20 percent they lost. They lost their shirt. And their pants."

Leaks emerge

In June 2011, two presentations of key findings from a KPMG audit of LIA's investment arm found their way online.

The leaked reports offer the first, and to this day the only, documentary insight into LIA's opaque and secretive investments. They expose, point-blank, a vast investment operation with no clear operating strategy. Derivatives and structured products, considered high risk and usually making up no more than a fraction of a sovereign fund's entire portfolio, made up 35 percent of LIA's.

Some investments were simply bleeding money away.

The KPMG audit was commissioned in May 2010 by Sami Rais, who refused multiple requests for interview. Someone who worked with him, and spoke anonymously, told us that when Rais was appointed CEO of LIA, in October 2009, LIA's losses had already reached $2.4 billion in monies that rightfully belonged to Libya's taxpayers.

When Rais asked for the term sheets to examine the deals that were incurring such losses, he was told there were none, or that they were in safety boxes but that the passcodes to the safety boxes had been forgotten. He spent his first few weeks chasing term sheets. Over the next several months, Rais blocked any new investments being made, even as the pressure to do so mounted.

|

Someone who worked with him [Sami Rais], and spoke anonymously, told us that when he was appointed CEO of LIA, in October 2009, LIA's losses had already reached 2.4 billion dollars |  |

In November 2010, armed with the findings of the KPMG audit, Rais presented to LIA's Board of Trustees, meeting in the city of Sirte, an outline of his recommended measures, including a plan to liquidate the failing investments.

Ten days after his return from the meeting, Rais received a letter from then Prime Minister al-Baghdadi Ali al-Mahmoudi - who headed LIA's Board of Trustees: "We thank you for your distinctive service, and wish you luck in your return to your previous role at the Central Bank of Libya."

The following month, a street vendor set himself alight in Tunisia. In January 2011, street protests erupted in Egypt. By February, Libya was in revolt. Come October, Gaddafi was gone.

After Gaddafi

In 2011, while the revolution in Libya was in full-swing, Muhssen Derragia was leading a quiet life in Britain as a lecturer at Nottingham University. One evening, he received a call from a friend of his who asked for his curriculum vitae. He then received a series of phone calls from increasingly senior figures in Libya, culminating in a call from Prime Minister Abd al-Rahim al-Kib.

He was offered a consultant-like position on the board of directors of LIA. It was part-time, involved four days of travel to Libya each month, and was flexible. He accepted in January 2012. A couple of months later, he found himself LIA's latest CEO.

LIA's assets had already been frozen under UN sanctions. In March 2011 the UN had identified LIA and its largest subsidiary, the Libyan African Investment Portfolio (LAIP), as "under the control of Muammar Qadhafi and his family, and potential source of funding for his regime".

Both were included in the sanctions list as pursuant to resolution 1970.

|

|

| UN sanctions targeted the LIA as Libya's revolution went into full swing [Getty] |

What this essentially meant was that LIA could not make any new investments, it could not administer changes to any of its existing investments - including its equity portfolio, regardless of market fluctuations - nor manage any of its bonds, even if they had since matured.

This resulted in real losses estimated at $721 million in 2014 alone.

Derragia was adamant that, losses notwithstanding, the freeze on assets must remain in place until the leadership structure of LIA was solidified and LIA was in a position to identify its assets, and monitor them.

He believed that unfreezing the assets before that point would leave them susceptible to embezzlement. So Derragia went about commissioning a new audit. To this end he released a tender, and four international auditing firms applied. LIA settled on Deloitte.

The results of the audit, to Derragia, provided a clear mandate: it identified what investments should be retained, and which should be liquidated. "This is where the real problems started," he says.

Derragia says that, from the beginning, there were two competing camps in LIA. The first, the technocrats, wanted to run the fund pragmatically, with a focus on the numbers. The second saw it as a big pot of money through which political alliances could be formed, maintained, and sometimes placated. To this latter group, liquidating any investment, even if it was costing LIA dearly, was equivalent to a real loss in power and influence.

The biggest problem was posed by the 550 subsidiary companies. The audit's results suggested that around 40 percent of these companies were not profitable and needed to be sold off. These included some oil refineries - one run by OilInvest in Switzerland, for example, was 50 years old, unmaintained, unable to keep up with Swiss environmental legislation, and incurring an annual average loss of 1.5 million euros - as well as outdated telecommunications industries, and businesses that competed with each other with the result that all lost out.

Contacted for comment, OilInvest told The New Arab: "In the face of increasing costs, coupled with ever-tougher competition from low-cost producers in India and China, the decision was taken to suspend the activities of the refinery at Collombey, where current conditions made the continuation of operations unsustainable."

The refinery appears to have ceased operations between April and June 2017, some six years after Derragia was calling for Libya's sovereign wealth fund to pull out.

The most ubiquitous example of unprofitable competition between its own investments was LIA's extensive hotel ownership network. A significant number of these hotels were run by LAIP through one of its subsidiaries (LAICO), others by LAFICO, a few others through smaller subsidiaries. There was, according to Derragia, no communication or strategic planning between these sometimes overlapping businesses.

|

The results of the audit, to Derragia, provided a clear mandate: it identified what investments should be retained, and which should be liquidated. 'This is where the real problems started,' he says. |  |

Derragia was adamant that firm, decisive action had to be taken: first, failing investments had to be sold off immediately and the money they generated re-invested in more worthy projects; and second, the remainder of the 550 companies had to be re-structured and streamlined, so that all service industries were grouped together, all telecommunication businesses together, etc.

"LIA can't manage 550 subsidiary companies effectively. No sovereign wealth fund can manage 550 subsidiary companies effectively," he said. Derragia wanted an operation that was smaller, neater, and smarter.

His proposals were met with tremendous resistance. He said the people in charge - naming two prime ministers under whom he served, Abd al-Rahim al-Kib and Ali Zeidan - didn't want to assume responsibility for any such decisions, necessary as they may be, because of what it may cost them politically.

Things may not have been calm in Libya, but there was a balance of sorts, and no leadership was prepared to disturb that. The only decisions they were willing to make concerned the continued running of operations on a day-to-day basis, maintaining the status quo.

"This just won't do when you have a $65 billion operation and 550 companies around the world."

|

|

| Former PM Ali Zeidan announced the end of Derragia's appointment in 2013 without naming a successor [AFP] |

In February 2013, Prime Minister Ali Zeidan announced the end of Derragia's mandate without naming a new appointment or forming a committee to oversee a transition.

"I had to go and tell Ali Zeidan and the board of trustees that they had to form a transition committee, that I needed to hand over my responsibilities."

No CEO of LIA has attempted an audit of its assets since Derragia's departure.

"I headed LIA when talk was rife of reform, modernisation, of the Libya of tomorrow. It later became clear that the entire 'Libya of tomorrow' discourse was a bitter farce."

A new chapter of 'naivety'

In January 2014, before the statuary limitations on the Goldman Sachs trades could expire, LIA - now headed by Abd al-Majid Breish - decided to attempt to recoup some of the money it lost by taking the bank to court.

Claim number HC14D00310 was submitted to London's Chancery Chambers on 28 January 2014.

The nine disputed deals were signed within four months of each other; two trades in Citigroup shares worth $200 million were signed in January 2008; three trades in EdF shares for $177 million in February 2008; a lacuna in March; then in April: a trade in Santander shares for close to 96 million euros, a trade in Allianz shares for 48 million euros, a trade in ENI shares for 96 million euros, and finally, a trade in UniCredit shares for 289 million euros.

They come up to a total of just over $1.2 billion dollars, earning Goldman a sweet $350 million in commission.

|

All trades were facilitated by Goldman, and all were equity derivatives deals, meaning LIA did not purchase any actual shares - but placed bets on the movement of shares to generate income. It turns out LIA bet the wrong way, and with the added burden of a global financial crisis, when the deals expired in 2011, the entire value of LIA's investment was worthless.

The argument LIA put forward in court was rather curious.

They chose to present themselves as a naïve and incompetent fund that was exploited by greedy financial executives.

Their claim cited emails between Goldman managers with heavy Orientalist undertones: "They are very unsophisticated, and anyone could 'rape' them," Ben-Brahim wrote to a colleague.

Another Goldman Sachs partner, Laurent Lalou, wrote: "You just delivered a pitch on structured leveraged loans to someone who lives in the middle of the desert with his camels."

Youssef Kabbaj, who became Goldman's man at LIA, was told by his manager, Ben-Brahim: "Stay a lot in Tripoli. It's important you stay close to the client on a daily basis. Teach them, train them, then dine them."

Kabbaj took his task seriously. LIA executives were invited to training workshops in London where they were treated to luxury hotel stays, expensive restaurants, and, according to statements submitted to court, entertainment costs that sometimes reached £22,000 ($28,800) in a single night.

Kabbaj paid special attention to Zarti's younger brother, Haitham. He took him along on all-expenses-paid trips to Morocco and Dubai, said expenses including five star hotel accommodation and the services of prostitutes (a "Michella" charged $600 for herself and a friend for the evening, according to Blackberry messages submitted to court).

The young Zarti was also given a spot on the highly competitive Goldman Sachs internship programme in New York.

LIA claims these actions constitute undue use of influence.

LIA also claims it did not know the investments were equity derivative products. Catherine McDougall, a witness to court on LIA's behalf, said that when she joined LIA on secondment from Allen & Overy's London office she discovered that LIA's staff believed they had bought actual shares.

Chris Wright, Asia editor at Euromoney who followed the story for a number of years, agrees that LIA did not have the world's most sophisticated team "by any means". There was a need to build capacity at the most basic level, he says - there weren't even enough computers, nor desks. Still, he insists that it did have some clever and capable people. He names Hatim Gheriani, a former Commerz Banker who would later go on to run HSBC in Libya.

Gheriani headed the Alternative Investments Team at the time the controversial deals were made. "One of the great problems I think that LIA faced in the trial against Goldman Sachs was it is very difficult to claim that people like that don't understand an equity derivatives contract."

Derragia, who headed LIA before Breish, said he did not think the evidence presented by LIA was strong enough, and that taking the case to court risked adding tens of millions in solicitor fees to their existing losses.

"All companies gift their clients," he explains, and by way of comparison, "you hosted me [for this interview] and bought me a coffee."

A coffee may not be a stay in Dubai's Ritz Carlton (and certainly not the evening entertainment that accompanied it), but is the judge to rule on the morality of the gifts in question, or on who was responsible for making the investment decisions that were made?

The court sat on 13 June 2016 for six weeks, and in October of the same year Justice Rose released a detailed jugement that ran for longer than 100 pages. She ruled in favour of Goldman Sachs.

LIA's balance on the Goldman deal now stands at $1.2 billion in failed investments, $350 million in commissions to Goldman Sachs, and a legal bill expected to exceed $82 million.

The legal cost has not been finalised, because LIA has launched an appeal.

Given the facts, Breish's confidence is surprising.

"It is only the first round," he says. "The appeal will be at the High Court; it will be presided over by three judges." "And," he continues, "these are not the only court cases. We have several cases we are pursuing, in Holland as well, holding officials accountable for corruption that took place between 2007 and 2008."

Breish didn't seem too concerned about the costs. When asked, he answered the question procedurally; he explained that the costs were paid through accounts that belong to LIA in Tripoli. Breish has a striking presence; there's a resemblance to Ronald Reagan that extends beyond the white-streaked jet-black hair.

Nicola Boulton, a professional litigator who specialises in fraud and money laundering, chooses her words carefully. "I do sometimes wonder if part of the problem isn't that litigation as a product sometimes gets sold to people, and that sometimes the people 'buying it' and paying for the process may sometimes not be fully in control or fully understand how difficult it is going to be."

If law firms fail to deliver on the promises they give clients, they do not carry the consequence. They get paid anyway.

The resonances are uncanny. LIA is suing Goldman Sachs for "exploiting" its financial naivety in its early days. Ten years older, LIA is today paying law firms tens of millions on premise and possibility. It is paying, with public money, for a different kind of "buying in". Who is responsible this time round?

Enyo Law, the firm representing LIA, refused through their PR representatives, Osbourne & Partners, to answer any questions.

But other court cases pursued by LIA did have backbone...

This is the first part of a two-chapter investigation into the practices and mismanagement of Libya's sovereign wealth fund. Read the second part here

Dr Deena Dajani is a researcher and writer based in London.