The US Electoral College 2020: Current projections and future uncertainty

The environment leading up to this election is nearly unprecedented. The United States continues to struggle to deal with the coronavirus pandemic and, though financial indicators like the stock market signal that the economy is doing well, real economic indices show the US economy to be in serious trouble, with millions unemployed or underemployed.

In addition to the simultaneous public health and economic crises, the United States has experienced devastating climate catastrophes and the nation has been gripped for months by social unrest sparked by long-term institutional racism, discrimination, and violence.

In any normal election cycle, disorder of this magnitude would sink an incumbent's re-election bid well before election day. However, through all of this, President Trump's approval rating has remained steady at nearly 45 percent, according to an average of recent polling, which is four points higher than his average approval rating over the course of his nearly four years in office.

Forty-five percent might not appear to be a winning level of support, but it is important to understand that the US Electoral College system is not based on popular support (i.e., the popular vote) as conventionally understood.

Instead, presidents win office by cobbling together the majority of Electoral College votes (270 of 538, or 50 percent plus one), which, in modern times, are allocated to the candidate who wins a simple majority of ballots cast in each state. For example, if a candidate wins 50 percent of all of the votes cast plus one in Texas or California, he or she receives all of that state's electoral votes.

The number of Electoral College votes each state receives is determined by the number of members it sends to the House of Representatives (which is based on a population ratio of about 650,000 per one seat) in addition to the two Senate seats each state is allocated. So, at a minimum, each state receives three electoral votes because every state has at least one House of Representatives member and two Senators.

This system makes "the goal of winning the individual states the primary concern of candidates" and multiple presidents in recent US history have capitalised on this feature to win the presidency without a majority of support from all of the country's voters.

A pervasive argument in the United States against electing presidents via the popular vote posits that, under such a system, presidential candidates would ignore less populous states and campaign solely in those states that harbour large populations.

|

Every few years, a small number of states - due to population growth or diversity, party outreach, or any one of several other factors - will shift from having a predefined outcome to one in which either party could win |  |

But in practice, the Electoral College system has the same effect. Most presidential campaigns identify a few states that are worth spending resources in. That is because most states have a partisan leaning - that is, the majority of voters there prefer the candidate of one party over the candidate of the other, no matter the individual - that makes the distribution of their Electoral College votes a foregone conclusion.

Then there are states commonly referred to in American parlance as "swing states" because they might "swing" between the two major parties from one election cycle to the next. However, every few years, a small number of states - due to population growth or diversity, party outreach, or any one of several other factors - will shift from having a predefined outcome to one in which either party could win.

Red States, Blue States, and Purple States

The US political system is dominated by two major parties: the Democratic Party, symbolised by the colour blue, and the Republican Party - or Grand Old Party (GOP), as it is known - which touts the colour red.

There are states that overwhelmingly elect Democrats to statewide and federal offices, thus are considered "blue states," and those that largely vote for the Republican Party and are referred to as "red states".

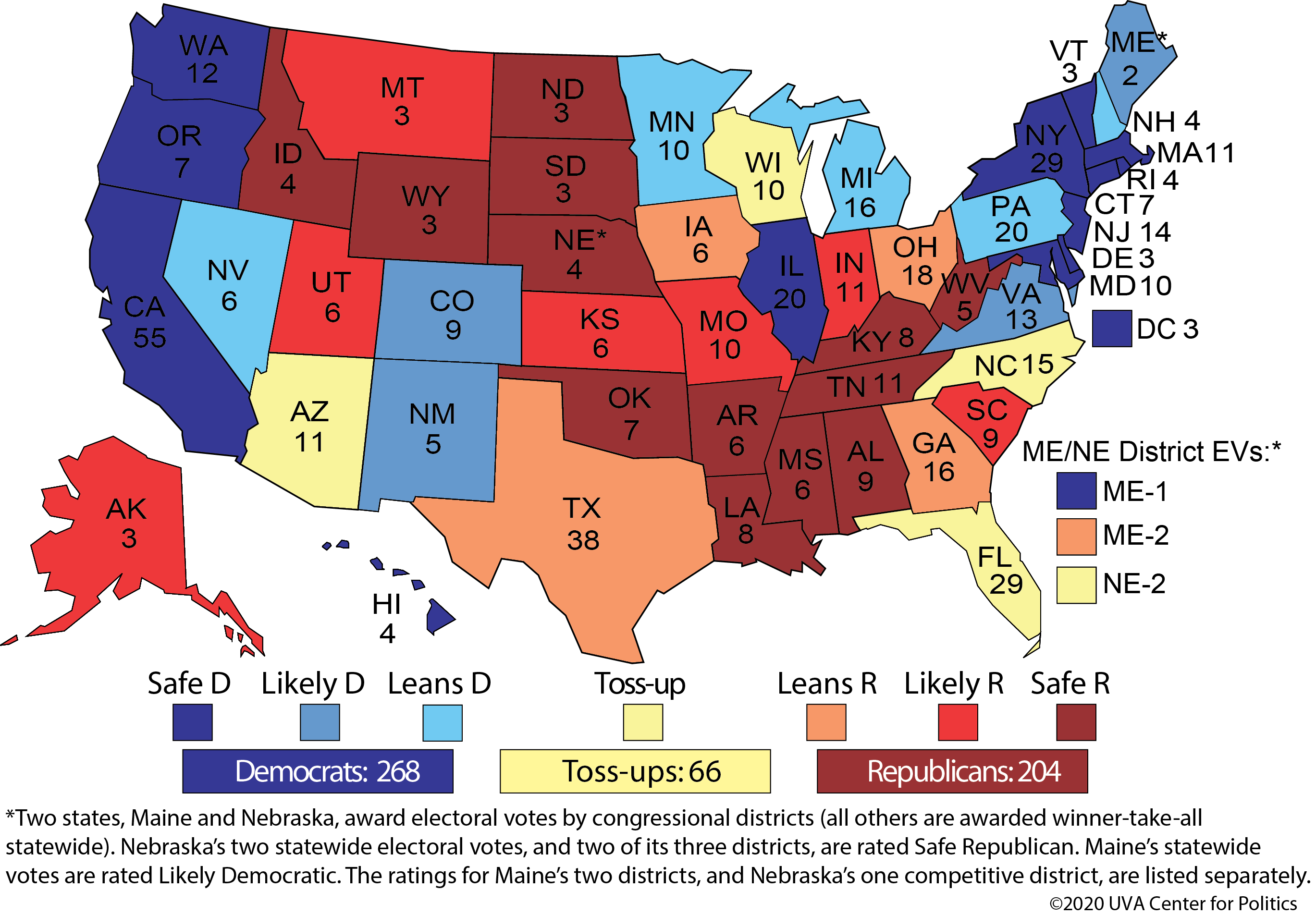

Before a presidential campaign even gets underway, there are largely a fixed number of Electoral College votes predetermined to go to the nominee for a specific party. Candidates from the Democratic Party, at least in the last two or three decades, have almost always won California (55 electoral votes), Connecticut (7), the District of Columbia (Washington, DC; 3), Delaware (3), Hawaii (4), Illinois (20), Maine (4), Maryland (10), Massachusetts (11), Minnesota (10), New Jersey (14), New Mexico (5), New York (29), Oregon (7), Rhode Island (4), Vermont (3), and Washington (12).

Republicans, on the other hand, tend to collect the electoral votes of Alabama (9), Alaska (3), Arkansas (6), Arizona (11), Georgia (16), Idaho (4), Indiana (11), Kansas (6), Kentucky (8), Louisiana (8), Mississippi (6), Missouri (10), Montana (3), Nebraska (5), North Dakota (3), Oklahoma (7), South Carolina (9), South Dakota (3), Tennessee (11), Texas (38), Utah (6), West Virginia (5), and Wyoming (3).

Adding up the electoral votes of all of these states demonstrates that, with just weeks to go before presidential ballots are cast, Democratic Party nominee Joe Biden already likely has 201 electoral votes to his name while President Trump can likely claim 191 electoral votes. That is largely without either candidate having to campaign in any of the aforementioned states.

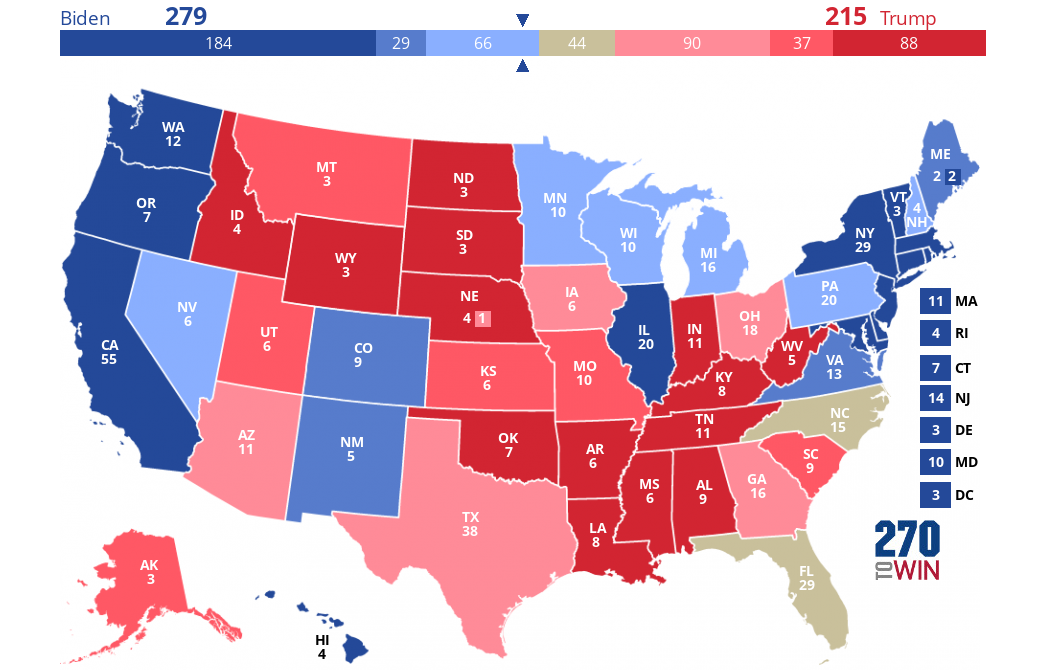

Electoral College map, 29/9/2020, at https://www.270towin.com/maps/ROdAW.png

Per their federal legislative delegations, Nebraska has five electoral votes (two for its Senate representation and three for the number of representatives it sends to the House) and Maine has four. The states split their electoral votes depending on the results of not just statewide tallies, but also based on the results of popular vote results within individual congressional districts (the geographic areas from which the aforementioned representatives are elected).

Twitter Post

|

In short, whatever candidate wins the majority of votes cast within the borders of Nebraska and Maine will automatically win two of their five and four electoral votes, respectively. Then, the remaining electoral votes are divided depending on which candidate wins the popular vote of the individual districts.

In 2008, this practice saw Republican Presidential nominee John McCain win four of Nebraska's five electoral votes because he won the majority of votes cast statewide and the majority of votes cast in Nebraska's 1st and 3rd congressional districts.

However, eventual winner Barack Obama won the majority of votes cast in Nebraska's 2nd congressional district, netting him the state's last electoral vote. President Trump successfully split Maine's electoral votes in 2016, winning the majority of votes cast in the state's 2nd congressional district, leaving Hillary Clinton with the two statewide electoral votes and the vote from Maine's 1st district.

If Democratic-friendly states are "blue" and Republican-leaning states are "red", states that are considered swing states are often characterised as "purple" due to the fact that both major parties can compete in those states but neither has consolidated support to reliably claim a majority of the vote prior to election day.

Of the 51 election entities that deliver electoral votes (50 states and Washington, DC), 11 have reliably been considered to be swing states in recent electoral cycles. Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin account for a total of 146 electoral votes. Minnesota recently has been considered a swing-state, but voters there have not rewarded the state's electoral votes to a Republican nominee since 1972.

Where will swing state votes go?

With over 30 days until the November presidential elections, prognosticators have identified a slate of swing states for the 2020 election, most of which come from the aforementioned list of traditional swing states, though some are only considered "purple" thanks to the unique circumstances facing the country at this time and the personalities of the presidential nominees themselves.

Polling data accumulated throughout the 2020 political season has painted a picture that looks as follows: Vice President Joe Biden is leading in most polling of traditional swing states like Michigan (16 electoral votes), Pennsylvania (20), New Hampshire (4), and Wisconsin (10), while President Donald Trump is leading in the traditional swing states of Iowa (6) and Ohio (18). Colorado (9), Nevada (6), and Virginia (13), having previously been considered "toss-up" swing states went for Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in 2016 and polling data suggests Joe Biden will also win those states.

Only North Carolina (15) and Florida (29) consistently poll as statistical ties, meaning that neither candidate has a lead on the other outside of the margins of error inherent in gathering the data.

If the results of the election follow these trends, and all other states stick to their recent historical trends, Joe Biden would have 279 Electoral College votes to Donald Trump's 215. That means Joe Biden would be elected the 46th president of the United States, even if he were to lose the toss-up races of North Carolina and Florida (which would result in President Trump receiving 259 total Electoral College votes, 11 shy of the 270 needed to win).

The unique nature of the 2020 race

Despite the polling data above, the current political environment in the United States, paired with the multiple crises facing the country and the polarising nature of President Trump, the 2020 election could see some states function as swing states this year that normally are not considered as such.

For example, even though Nevada, New Hampshire, and Maine have recently voted for the Democratic nominee, polling there indicates that the races are closer than they have been in the past. It is important to remember that Donald Trump won a single electoral vote in Maine in 2016; so it would not be a surprise if he repeated that feat. The polls of Nevada and New Hampshire often fall within the margin of error, meaning that, between now and November, the races could swing in either candidate’s favor, putting President Trump within striking distance in those states.

But on the other hand, some traditionally red states have shifted dramatically in Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s favor. Arizona, which has voted for the Republican candidate in every election since 1972, with the exception of 1996, is proving to be a serious problem for President Trump. Poll after poll shows it to be, at best, a toss-up, and at worst a win for Mr Biden.

|

President Trump's low approval ratings have put Texas and Georgia, traditionally 'ruby red' states that hardly ever elect Democrats for any major statewide or presidential election, into play for Vice President Biden |  |

Furthermore, President Trump's low approval ratings have put Texas and Georgia, traditionally "ruby red" states that hardly ever elect Democrats for any major statewide or presidential election, into play for Vice President Biden. If President Trump were to lose either state's electoral votes, his path to the 270 electoral votes needed to win would shrink to a near impossibility.

Finally, Biden is also in a position to snare a single electoral vote from Nebraska's 2nd congressional district, as his running mate Barack Obama did in 2008.

Under normal circumstances, Joe Biden's victory would look much more certain considering that his polling averages put him in a position to reach 270 electoral votes much more easily than President Trump.

Could states use antiquated tactics to decide Electoral College?

As it stands, former Vice President Joe Biden has a statistical advantage in reaching the 270 electoral votes necessary to secure victory. But there are serious concerns this year about how an Electoral College victory will be determined.

The coronavirus pandemic threatens to subdue in-person voter turnout but significantly increase the number of ballots cast by mail. This means that it will take much longer for votes in nearly every state, especially in those with little or no mail-in voting infrastructure, to be counted and increases the chances of votes being lost, discarded for minor errors, or otherwise being uncounted.

Americans are accustomed to election outcomes being broadcast the night of the election, but there is a minute chance of this happening in 2020. That means that a notoriously impatient electorate - perhaps encouraged by President Trump, who has and continues to cast aspersions on the legitimacy of American elections - might grow to distrust election results if they trickle in over days and weeks.

Hypothetically, this public agitation could result in an Electoral College decision on 14 December, 2020, not used since the mid-19th century. According to Article II of the US Constitution, the allocation of Electoral College votes are cast by electors and the decisions for how to appoint these electors are left up to states' legislatures to decide.

|

Technically, there is nothing unconstitutional about a state legislature ignoring the state's popular vote and deciding to choose electors as it sees fit |  |

Every state and Washington, DC, since the 1860s, has tied the appointment of electors to the result of the popular vote. However, that is not necessary, as the Supreme Court affirmed in the 2000 Supreme Court case Bush v. Gore.

According to the justices who handed down that Supreme Court ruling—which halted a ballot recount in Florida and essentially gave the election to George W. Bush—there is no inherent right for states' voters to have a say in how electoral votes are disbursed. Technically, there is nothing unconstitutional about a state legislature ignoring the state's popular vote and deciding to choose electors as it sees fit.

In a scenario where, weeks after the 3 November election, there is no clear winner and President Trump and his political allies have cast doubts on the legitimacy of what results are made public, state legislatures in some of the most crucial swing states could step in and choose a winner.

For example, some fear that Republican-held state legislatures in states like Ohio, Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Texas, or Georgia would usurp the will of voters there and appoint electors to cast those states' Electoral College votes for President Trump - even if the results of those respective states' popular votes are unclear or not completely tabulated.

Read also: The progressive vote and the 2020 election

This opens up a whole new set of legal electoral questions when considering that the Democratic governors of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania might challenge their legislatures' decisions. There is no guarantee that the election devolves into this kind of legal chaos, but these are unprecedented times, so it would be neglectful to ignore the possibility that it might happen.

With just weeks before Election Day 2020, polling data seems to favour Vice President Joe Biden's bid to unseat incumbent President Donald Trump. However, there are a host of undecided voters who could swing the election in favor of one candidate over the other. In addition, there are esoteric legal mechanisms that could decide an election marred by allegations of voter suppression, voter fraud, and other unpredictable developments.

Marcus Montgomery is a Junior Analyst for Congressional Affairs at Arab Center Washington DC.

Follow him on Twitter: @marcuscmontgo

This article was originally published by Arab Center Washington DC on 9 October 2020, and was republished with permission.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, al-Araby al-Jadeed, its editorial board or staff.