Election 2020: Millennials in California strike a tone of cautious optimism

Seven millennial voters huddle around a television in California to watch live Election Day updates. Gathered in an apartment in the San Diego neighbourhood of North Park - described by Forbes magazine as one of America's best hipster neighborhoods - the group is made up of four women and three men, all in their 30s.

In true hipster fashion, they met in a kickball league, a sort of ironic, alcohol-infused spin on traditional recreational sport. Five are Democrats, the sixth a middle-ground Republican, and the seventh a libertarian.

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the idea of gathering with friends seemed ludicrous to this group. Like many millennials, they adhere to pandemic restrictions more closely than their boomer parents who are arguably more at risk from the virus. They are the type to always wear a face mask, follow social distancing guidelines, and discuss in hushed tones the audacity of spring-breakers in Florida.

Yet as the months wore on and no end to the pandemic was in sight, the seven friends decided it would be safe enough if they only spent time with each other, and decided to make a pod.

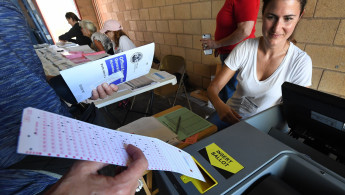

The day before Election Day, nearly 100 million Americans cast an early vote, including 11.2 million Californians. Of the golden state's likely voters, approximately 20 percent are millennials who tend to be more liberal. They generally believe in immigration and healthcare reform, science, and social justice initiatives.

Recent politically fraught events including wildfires ravaging the state, the coronavirus pandemic, and nationwide protests against racial injustice and police brutality following the killing of George Floyd have driven young people to the polls more than ever before. Many say combating racial injustice was the primary impetus driving them to vote.

|

Of the sunshine state's likely voters, approximately 20 percent are millennials who tend to be more liberal. |  |

Of this group of seven, all but one support increased taxation for social welfare initiatives. Millennials tend to be jaded by the wealth gap between themselves and their boomer parents, who hold nearly 60 percent of the nation's wealth, while millennials have under 5 percent.

This wealth disparity is further exacerbated by consequences from the pandemic: American billionaires grow infinitely richer while essential workers risk their lives every day, often for minimum wage. The $4.75 per hour Californian minimum wage workers earn over the national average ($12 versus $7.25) seems laughable in North Park, where the average home cost is nearly $700,000, far higher than the national approximate $230,000 average.

When asked about the wealth gap between millennials and boomers, D, a project manager, quips, "Do you know the millennial retirement plan? It's when you run out of money to pay for your depression meds so you just stop taking them and then off yourself by eating a Tide Pod."

Facing one of the worst economic outlooks of any generation since the Great Depression, bleak humour often becomes an outlet. The first generation to grow up with the internet, they often pride themselves on their desire for authentic content, and ability to navigate multiple terrains even while being the most downwardly-mobile generation in nearly a century. This nihilistic outlook also leads to more skepticism about the election than seen in other generations.

Twitter Post

|

While the hope for change inspires much millennial voter turnout, many are doubtful that this election will actually change anything. This paradox leads to a cautious optimism. "Last time I was at work when we learned that Trump won, and it was awful," D says. "This year I wanted to just stay home alone. But honestly? I'm cautiously optimistic, so I decided to come to the Election Day watch party."

Of this group, all but two voted for Joe Biden in the presidential election. M, who works in advertising, says she always votes along party lines even though she "doesn't much like Donald Trump." E, who works in the service industry, voted for Jo Jorgensen because he "wants to vote for who he actually believes in" despite his desire to oust Trump.

As the night wears on, debates about local propositions turn heated. Proposition 22 is one of the most important local issues this year in California. It would allow ride-sharing apps like Uber and Lyft to keep drivers as "independent contractors", and exempt these companies from guaranteeing minimum wage, paid sick leave, and unemployment insurance.

But one Uber driver says "A yes vote on Prop 22 means I can continue to feed my family. Independent contractors have a place in this economy." B, a socioeconomic analyst, differs, arguing that the gig worker economy is exploitative.

The group also discusses Proposition 16, which would overturn California's ban on affirmative action and allow schools and public agencies to take race, ethnicity, and sex into account for school and job decisions. "I think affirmative action is actually itself racist," says M, while J vehemently disagrees.

"We need to make up for systematic oppression, and this is the only way to do it," he says, slowly taking a hit from a marijuana vape pen, made legal recreationally in California in the 2016 vote via Proposition 64.

|

While the hope for change inspires much millennial voter turnout, many are doubtful that this election will actually change anything. |  |

The conversation soon turns to voting rights for convicted felons. In California, convicted felons can vote after they have completed prison time and parole. Proposition 17 would allow convicted felons to vote as soon as their prison sentence is over, even while on parole. The group is split on the proposition, arguing about the implications of criminality and rehabilitation.

Even though the seven millennial voters don't agree on everything, there is one thing that unites them: 2020 has been a rough year for everyone. The coronavirus pandemic means the group can no longer play kickball together anymore. Several members of the group lost their jobs due to the pandemic, and one even lost a family member.

Still, that whimsical sense of cautious optimism pervades the group. They hope that they can be the change they want to see in the world, that their vote really will matter.

At the end of the night, election results still nebulous, E quotes Biden's campaign speech from the previous day - but with a slight twist: "The power to change the country is in our hands." And for this group of millennial voters, the promise of that power to change is almost enough.

Suzy Woltmann is Senior Editor at Misbar, a news fact-checking site. After working in journalism for several years, she earned her PhD in literature from the University of California San Diego, where she taught literature and writing classes.

Follow her on Twitter: @SuzyQtheWriter