Living histories: Potent longings for fragile homelands

Spanning graphic design, painting, photography, poetry, sculpture and installation, the works marry contemporary and ancient aesthetics. The British Museum setting - with the exhibition held in the rotational space between the Iranian and Ottoman sections - lends a sense of both urgency and historicism that makes for a compelling viewing experience.

Curated by Venetia Porter, a leading expert in the Islamic and contemporary Middle East, the exhibition was inspired by the 2014 book Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline edited by Malu Halasa, Zaher Omareen and Nawara Mahfoud. The Al-Saqi Books publication was billed as "a celebration of a people determined to reclaim their dignity, freedom and self-expression. It showcases the work of over fifty artists and writers who are challenging the culture of violence in Syria".

The exhibition opens with posters from the Syrian artists' collective known as The Syrian People Know Their Way.

"[It was Halasa who] first alerted me to the phenomenon of this anonymous collective of artists from the beginning of the uprising in Syria," said Porter.

The collective produced posters, circulating them on Facebook, printing them out and taking them to demonstrations.

"This was a medium that was obviously very ephemeral," says the curator. "And what we did was unusual in that we got the digital files printed out onto archive paper. But by turning them into something we can keep... a kind of print making - it means that people can actually come and see the work, which is really important."

The British Museum's historical approach to contemporary art is well-suited to the display of posters, whose 2011 origins betray a certain kind of pluck and optimism, and hope for a better future.

The exhibition ends with a poignant new installation by 54-year-old Issam Kourbaj, with accompanying text by poet Ruth Padel, offering further current resonance with the Syrian tragedy.

Kourbaj is the artist who installed miniature models of Syrian refugee camps at five sites across London in 2015.

Scars was inspired by "wasters" - misshapen bits of pottery from medieval Aleppo in the museum's collection - and consists of four elements. The odd pieces of pottery jugs speak to a proud history and a shattered reality, while a twisted typewriter and haggard sketchbook evoke the fight for freedom of expression and, according to the artist, the three-year siege of Homs that led many Syrians to flee their homeland.

Dark Water, Burning World uses miniature boats made of burnt matchsticks - at once modern and ancient - to evoke the dangerous sea journeys of Syrian refugees.

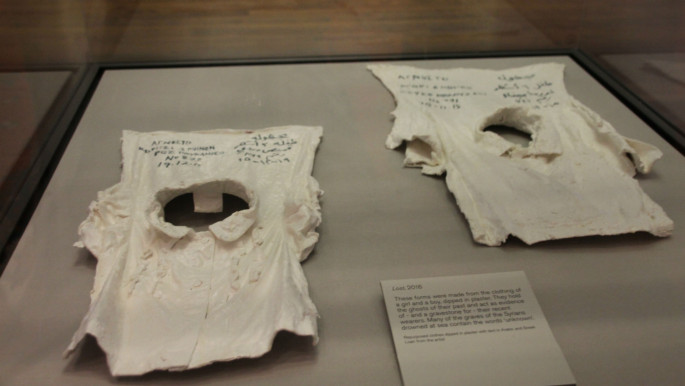

The last part of this set piece for the displaced is the haunting Lost, made from repurposed children's clothes coated in plaster with Arabic and Greek writing. Evocative of tombstones, the work recalls the deaths of young ones lost in the Mediterranean.

|

|

| Issam Kourbaj's 'Lost' [Hadani Ditmars] |

From impassioned revolution to the death of innocents, the exhibition offers a circular journey, punctuated by works that capture the daily struggles of Syrians as well as an intriguing Iraqi symbiosis.

Sula Hafazi, a 40-year-old Syrian artist, has provided a digital print on archival paper of a bride and groom wearing gas masks in a darkly comic highlight.

"I wanted this artwork to be about any conflict situation with accompanying humanitarian issues. However, these illustrations were born out of my experiences in Syria," said the Frankfurt-based artist.

Fadi Yazigi's Picasso-esque pen and ink drawing on rice paper expresses the daily joys and challenges of Syrian life. The 51-year-old's celebration of the quotidian features figures that are all a little off balance - one is upside down, another falls from his horse - but there is a sense of enduring Syrian spirit.

|

|

| Works by the Syrian People Know Their Way collective [Hadani Ditmars] |

An accompanying online catalogue notes that Yazigi, who continues to live in Damascus, "points to the positives, which include Syria's wonderful light and the fact that, above all, the country is still his home".

It quotes the artist as saying: "Maybe there are no longer any birds here, but I'm still trying to capture a mood... I can't stop working; art is not only part of my survival - it's also a way of looking for a solution."

Four prints from 44-year-old Damascus-born Jaber al-Azmeh's Resurrection series - initiated in 2011 - are revealing. Azmeh, now based in Qatar, photographed Syrian journalists, poets, artists and actors asking them to hold a copy of al-Ba'ath - the official government newspaper - and write on it.

One particularly powerful portrait features journalist Alma Entabli, who wrote the words: "The mask has fallen."

The portraits in effect take back the Syrians' agency. Instead of being anonymous victims in headlines, they're controlling the headlines - and daring the viewer to see them as real people.

Prominent 66-year-old Syrian artist Youssef Abdelke - who was once a cartoonist jailed by Hafez Assad - fled to the West, only to recently return to his homeland where he was imprisoned and then released after a huge public outcry. His simple-yet-powerful charcoal on paper Sardine evokes a fish trapped in a can.

A strong graphic and even cartooning quality is found in works such as 37-year-old Azza Abo Rabieh's 2011 etching on paper Our Revolution is on the boot of our government from the series Syrian Book, 36-year-old Houmam al-Sayed's sphinx like pen on paper figure; and especially in Hamid Sulaiman's eerie ink on paper drawing of children demonstrating above an aerial view of a city, their faces veiled by placards.

But it's the artists' book section that fuses poetry - namely by Syrian poet Adonis - and the work of Iraqi artists and one Algerian artist - that offers a deeper sense of collision between the ephemeral and the historical.

A piece by 64-year-old Syrian artist Ziad Dalloul, who has worked extensively with Adonis, is from a series of etchings/artist books named Book of Cities.

His abstract textural landscapes are paired with a snippet of a longer poem by Adonis about Damascus.

"We are accustomed to saying that Damascus does not sleep, and we also say, when she sleeps, her slumber is as light as a dream… Damascus, you are our life - but what is this life that gives us only death?"

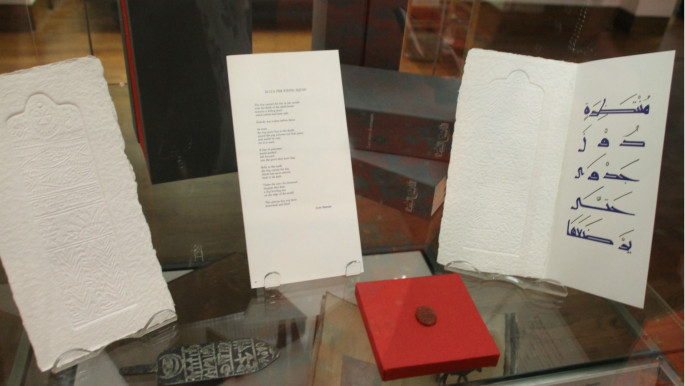

Algerian Rachid Koraichi's elegant calligraphic ode to the monks killed by assassins in the monastery of Tibhirine in Algeria in 1996 links their story to the Quranic tale of the Seven Sleepers - a group of Christians fleeing from the Roman emperor Decius by hiding in a cave with their dog and awaking a few hundred years later. It speaks to ongoing and historical persecution, and is accompanied by a text by John Berger called The Firing Squad.

|

|

| Rachid Koraichi's Les Sept Dormants, Artist book, etchings and calligraphy, 2003-2016 [Hadani Ditmars] |

The artist's book of Dia Azzawi, the 78-year-old Iraqi master, overlays the words of Adonis on a colourful background:

A horizon - a mixture of lights and colours

No divide between earth and sky,

And space has the shape of a staircase like a musical scale.

O winds of meaning,

forever going up and down

Do you ever get tired?

Peace unto that dawn

whose hands get chafed climbing the first steps.

Ammar Dawood, a 60-year-old Iraqi artist who now lives in Sweden, experiments with collage and painting techniques in his artist book, with map-like traces fused with cuneiform, reading like spiritual cartography of a lost homeland.

Compact Home 7 is a mixed media artist's book by 51-year-old Iraqi artist Mahmoud Obaidi, who fled Iraq for Canada in 1999. The work features gazelles reminiscent of Sumerian cave art, collage, fragments of metal and an accompanying suitcase as a "home" for the work.

The book developed following his realisation that "all our days are spent in the hope that one day we will see our homeland or we will return to our homeland. Homelands may be a deception or a trap... I do not know what homeland means... I believe that all countries are homelands for their inhabitants, so why should they not be homelands for me?"

A final, punctuated afterthought emerges in Antiquity Thieves, a photo by 37-year-old Egyptian artist Heba Y Amin, part of her series Objects in Exile that evokes cultural loss.

The image of two proud would-be tomb-robbers on a motorbike riding through the desert is the final view before the exhibition disappears into the larger, more civilised looting space of the museum.

Living histories: Recent acquisitions of works on paper by contemporary Arab artists is at The British Museum in London until October 22. Admission is free.

Hadani Ditmars is the author of Dancing in the No Fly Zone: a Woman's Journey Through Iraq. A former editor at New Internationalist, she has been reporting from the Middle East for two decades. Her next book, Ancient Heart, is a political travelogue of Iraqi heritage sites.

Follow her on Twitter: @HadaniDitmars