The Encyclopaedia of Islam, a treasure for all ages

It took the 23 years from 1913 to 1936 to finish and publish the first edition of the renowned English-language Encyclopaedia of Islam. It took half a century to finish the second edition. Work began on a third edition in 2007 and it has yet to be completed.

Time spent in academic research is very different from time in the considerations of everyday life. It is as if they are two different entities: A time of patience and diligence, and a time of speed and haste.

We live in the age of speed, we are told, a term coined by the nations that brought this age into existence through scientific progress and through dominance that has left its mark on everything in our "blue as an orange" world, as Paul Eluard's poem goes.

More than a hundred years after the start of the encyclopaedia project, we have found no time to translate it, the very least we could have done, let alone the time to write one. Let alone to put into one the same calibre of academic work and research that would bring us closer to our forebears, the sources of Islamic civilization, and the people to whom credit goes for our good reputation in the past.

Today we live on its sweet memory, sedated by our glorious golden past, oblivious to our present. And it seems as though our ancestors were light years ahead of us.

Will it ever be fully translated?

| We live in the age of speed, we are told, a term coined by the nations that brought this age into existence. |

There is a Tunisian-led project to translate the encyclopaedia, so there is hope. The first attempt was incomplete, partially translated in Egypt and published in 1998 under the title A Concise Compendium of Islamic Knowledge. The project stalled after that.

Meanwhile, Brill did not content itself with the first edition. It followed it up with a second, and is preparing a third, not because Brill has plenty of time to do so, but because it wanted to take into account criticism of the encyclopaedia.

Years later, the publisher realised it would be best to work with the help of Arab and Muslim scholars, and proceeded to do so. Though they do not account for the majority of contributors to the encyclopaedia, but naturally we can detect the traces of their efforts, especially in relation to studies of the Arabic language.

After all, Arabic is the bedrock, the core of this work. There can be no credibility for a "foreign" scholar on this subject matter unless the scholar has a thorough knowledge of Arabic. Recall in this regard the constructive criticism Arab researchers levelled at an article by Gotthold Weil on Arabic poetic meters.

The criticisms were published in Arabic periodicals. We do not know if they ever reached Brill. Weil had contributed to the first edition of the encyclopaedia, and his article was published in the second edition as well, as though the views of Arab scholars were superfluous.

No doubt, the encyclopaedia is a huge accomplishment. Yet the idea of revising and updating it with each edition is fundamental and essential, and entails respect not only for academic research, but also for the reader. Its publishers and authors understand that it has become an indispensable reference, a fountain of knowledge on its subject matter.

For all these reasons, it is crucial to talk to the project manager overseeing the third edition, Abdurraouf Oueslati. It is an ongoing work, so we have to communicate and provide input on the Islamic encyclopaedia, or the Encyclopaedia of Islam if we go by the literal translation of its name.

There is a linguistic difference between the two terms. The difference has less to do with the contents of the encyclopaedia and more to do with the usage of the terms today.

Islam the religion or Islam the civilisation?

When it is intended to link us Arabs as a nation to terrorism, Islam suddenly becomes our religion alone. Yet when it is linked to a particular civilisation, the Islamic civilisation, its geographical scope is suddenly expanded.

Western eyes start seeing it as a broad and diverse entity, spanning the Arab world and linking it to Indonesia, India, and other parts of the world.

| We must think about working on our own encyclopaedia, regardless of the time something like this would take us. |

This is the view of the dominant strong other, the West, whose hegemony has almost overrun everything. Yet instead of complaining, we must think about working on our own encyclopaedia about our faith and civilisation, regardless of the time something like this would take us. But perhaps we have no time, being preoccupied with more urgent matters, perhaps. We are in the age of speed and haste after all.

And hasty it was too, it seems, time at the Egyptian museum. There, at the centre spot, inside a glass box, lies one of the most beautiful relics of ancient Egyptian art: the mask of Tutankhamen, the masterpiece that dazzled the entire world.

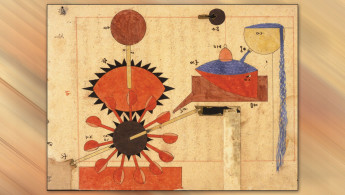

Imagine how much time it took to make the mask, perhaps as long or longer than it took to make the Islamic Encyclopaedia. Made of pure gold, with quartz for eyes and lapis lazuli for eyebrows, that masterpiece was the work of ancient Pharaonic craftsmanship. Was there only one ancient Egyptian craftsman or many? A superfluous question perhaps, because the crux of the matter is the outcome, which says that almost immeasurable Time is what it takes to accomplish anything eternal.

But we are now in the age of speed. When, in mysterious circumstances, the mask's beard fell off, glue was brought in hastily, to glue it back on speedily. An Egyptian person or perhaps several people did that deed. There was no time, no time to wait, because we are in the age of speed.

Like casually committing a crime, epoxy resin was used on gold and precious stones, haphazardly gluing the chin to the mask like an insult glued to an identity.

This is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.