Muslim Americans remember Muhammad Ali's fight for his faith

In December, the boxing legend issued a statement criticising Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump's proposal to ban Muslims from entering the US.

Ali called on fellow Muslims to "stand up to those who use Islam to advance their own personal agenda".

Ali, who died on Friday aged 74, endured public scorn when he joined the Nation of Islam as a young athlete.

Decades later, long after he had achieved worldwide renown, he continued advocating for Muslims in the US who felt their religion made them political targets.

"American Muslims would be well-served to look at the challenges that Muslims such as Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali had to deal with," said Dawud Walid, executive director of the Michigan chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

Ali's lesson "from that difficult period is that although he was criticised and marginalised for his beliefs, there were many people who were not Muslim that came to his defence".

"There are people in America today of goodwill who are not Muslim who are willing to stand with us. But we have to be the ones who have to be courageous and stand up for ourselves and be unapologetically Muslim and American."

|

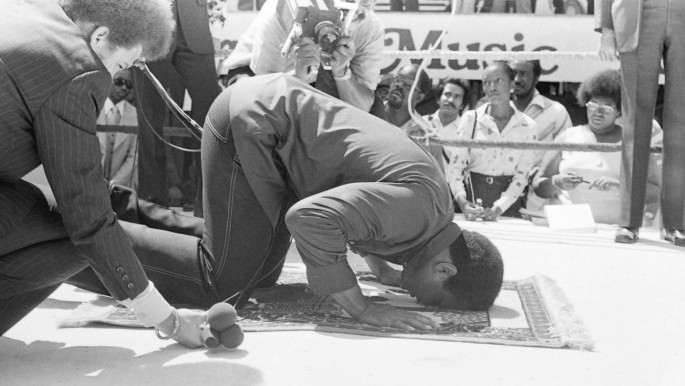

| Ali did not hesitate to pray in public, such as during this August 1976 press conference in New York [Getty] |

| Read more: Death of The Greatest: The Arab world reacts to the death of Muhammad Ali. |

Ali's persistence both inside and outside the ring won over many critics.

While detractors did not always agree with him, many came to respect his principled stands.

Muslims in particular praised his humanitarian work, which included lending his name and time to numerous relief campaigns and helping to secure the release of American hostages in Iraq.

Born Cassius Clay in a segregated Louisville, Kentucky, Ali angered many Americans when he refused to fight in Vietnam.

But in 2005, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W Bush.

Lyndon Bilal, commander of the Muslim American Veterans Association, said through his "love, character and courage", Ali had "always been a friend of soldiers and America".

His long list of admirers includes many other athletes, especially other Muslims.

Detroit Lions running back Ameer Abdullah said Ali's devotion to Islam "will always be an inspiration for me".

"Ali was a true ambassador for the Islamic community for his courage and devotion to his faith through very trying times," Abdullah said in a statement. He "carried himself with absolute dignity when standing up for his faith in trying circumstances".

|

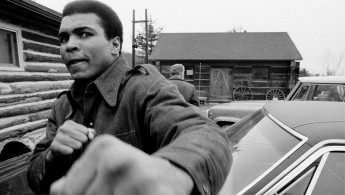

Ali lost millions of dollars in potential earnings when, at the peak of his career, he was banned from boxing for three-and-a-half years for refusing to give up his religion and declaring himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War |  |

Imam Abdullah El-Amin, founder and board chairman of the Muslim Centre in Detroit, said Ali lost millions of dollars in potential earnings when, at the peak of his career, he was banned from boxing for three-and-a-half years for "refusing to give up his religion" and declaring himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War.

That episode, El-Amin said, "gave us a lot of courage."

Like many African-Americans, Ali's first foray into the faith was through the Nation of Islam, the black nationalist movement started in Detroit.

He joined others in moving to a more integrated, traditional form of Islam in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, El-Amin said he and Ali attended many of the same meetings for humanitarian groups and events in Detroit and Chicago, including visits to Ali's home.

He remembers Ali for his "gentle spirit and generosity" - but also as a merry magic prankster who would pretend to levitate, but reveal to impressed guests how he did it, lest anyone think he was some type of "guru".

|

He remembers Ali for his gentle spirit and generosity but also as a merry magic prankster who would pretend to levitate but reveal to impressed guests how he did it, lest anyone think he was some type of guru |  |

Walid, who was to lead prayers for Ali on Sunday at a Detroit mosque Ali visited, remembers when Ali first came into his home - in the form of an action figure.

As a child in the 1970s, Walid said he was "just having fun playing with toys", but the doll from his parents proved to be a "subtle" influence on his eventual journey to Islam.

"It not only made Muslims and Islam into something not threatening but actually... a type of nobility," Walid said, "That continued with me."

Ali "represented to me what it meant to be a Muslim man - at a very young age".

One of Ali's final messages was defending his faith. Trump's comments, Ali said, "alienated many from learning about Islam".

El-Amin described Trump's rhetoric as contributing to "hatred in our society", which Ali spent years fighting.

|

El-Amin described Trump's rhetoric as contributing to 'hatred in our society,' which Ali spent years fighting |  |

"People just wanted to look at him as a great fighter, but he was a great fighter for justice as well," El-Amin said.

"The best thing we can do for him is talk about his humanitarian work in the world," he added.

"At the same time, we have to talk about his pushing... to enhance the human spirit. That's what he should be known for."