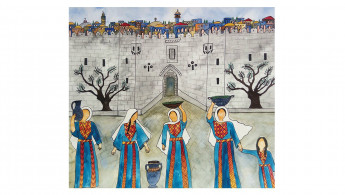

Between tradition and change: Praise for the Women of the Family

Where people exist, stories abound. Mahmoud Shukair's novel, Praise for the Women of the Family (Interlink Books 2019) reads like a collection of colourful narratives of the al-Abd al-Lat Palestinian Bedouin clan, hovering on the threshold between tradition and change.

Yet there is only one female narrator, and the reader has to rely on the perceptions of the male members of the family for a portrayal of the women despite the latter being protagonists in their own stories.

The book is set in the aftermath of the Nakba and the years that followed, tracing the political and social changes as loyalty towards the clan gradually gave way to individual aspirations and opinions.

Muhammad Al-Asghar, one of Mannan's sons, works as a clerk in a sharia court dealing with marriages and divorce. Through his work, he gains an invaluable source of stories as well as insight into how opportunities for emancipation have to overpower social expectations.

Muhammad's narrative is perhaps the most insightful, offering perspectives from his own personal situation – being married to a divorcee who is also barren, as well as the interactions of his mother, Wadha, who is one of his father's co-wives. Imbued with all the stories and anecdotes, Muhammad wishes to become a writer, contrary to his father's expectations that he takes on the clan's leadership.

|

|

Wadha is in a perpetual struggle and, like her husband Mannan, also has to contend with her decreasing influence as technology makes inroads and her storytelling charm is no longer sought. Her preoccupation with Muhammad's childless marriage, as well as Falihan, Muhammad's half-brother, is just an indication of the clan's tumultuous lives.

Against a backdrop of turbulent politics, Falihan becomes a drug smuggler and lives precariously, dealing with Israelis and largely steering clear of politics. His fate is ultimately decided by the jilted fiancé of his second wife Rasmiyya.

Falihan's impetuous character shifts dramatically when the novel zooms in on his relationship with Rasmiyya. Despite the misgivings attributed to Falihan's character, he exhibits none of the egoistical traits of his other brother 'Atwan, who leaves his wife and son to pursue opportunities in Brazil. 'Atwan eventually marries a Brazilian woman and perpetually postpones his return to Palestine, each time refining his excuses for his absence.

The women of the family, meanwhile, are ensconced in a society that is determined by men. At the slightest change, the women collectively seek to defend themselves, at times incurring additional damage against each other if a woman defies tradition.

Rasmiyya incurs insults regarding the beginning of her relationship with Falihan and her refugee status is also derided by the women. Sanaa meanwhile has to face scrutiny and suggestions that her husband marries a second time in order to have children. Both Rasmiyya and Sanaa are portrayed as outsiders; both seek to challenge the boundaries which govern village life.

However, the reader is also aware that both women are encouraged in their rebellion against stereotypes by their husbands. In the village, it is perhaps a luxury which other women have not experienced. 'Atwan's first wife is not portrayed as seeking a divorce – she remains estranged without resolution, bringing up their son alone.

It is Muhammad who remarks about the necessity of including women in political and social change. In a discussion with his father, Muhammad distinguishes between rituals, religion and practice. "These rituals don't mean that the women's situations are as they should be." Muhammad is an exception among the men portrayed in the novel, most of who are in polygamous marriages.

Muhammad also recognises the similarities between the cases he comes across in his work at the court and back home with the clan. His observations are a critique of society's impediments to progress and, indeed, Palestinian liberation.

"I saw a connection between wronging women and losing the country, and told some friends that we would not be able to free the country as long as women were oppressed."

|

|

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: The Parisian: The First World War through the eyes of a Palestinian |

Shukair's choice of title for his novel raises several observations. The women's presence and roles narrated by males is in itself a prime indicator of inequality. Indeed, the women's characters are vivid and make an impression even though there is less space for direct female narratives.

But readers are still largely acquainted with the male perspective of the female role – a critique in itself, as is the title, which can have various interpretations, including a reflection of the condescension which Muhammad strives against and which distinguishes him from the rest of the males in the family, who discuss women in terms of marital relationships rather than independent individuals.

Order your copy of Praise for the Women of the Family here

Ramona Wadi is an independent researcher, freelance journalist, book reviewer and blogger specialising in the struggle for memory in Chile and Palestine, colonial violence and the manipulation of international law.

Follow her on Twitter: @walzerscent