Unlearning patriarchal standards with Believing Women in Islam

Many women, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, have at some point questioned what Islam says about their role in society, in the household and their overall womanhood. Islam is in many circles across the world viewed as a religion that subjugates women, denies women their rights to property, forces them to get married and stay in abusive marriages, and speaks to them in the Quran through the voice of a man.

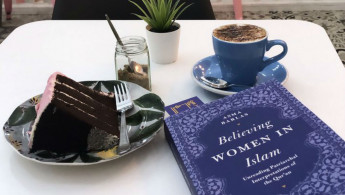

Believing Women in Islam: Understanding Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qur'an by Asma Barlas is a book that studies the role of women through various lenses. In her three-part book, she assesses the epistemology behind what are often viewed as patriarchal interpretations of the Quran, addresses particular concerns of women regarding what is commonly perceived to be rulings and then assesses the arguments of her critiques to unread interpretations of patriarchy Islamic texts.

While Barlas acknowledges she addressed the topic as a woman who believes in Islam and as a practicing Muslim, she chose to adhere to an academic approach to speaking about the Quran, focusing specifically on the content of and context surrounding the Quran and how interpretations have evolved over time.

She chose to give a specific focus on the importance of epistemology when interpreting the Quran; Barlas makes a point that verses of the Quran which seem at face value problematic, such as the practice of giving men more inheritance than women, are viewed ahistorically.

In seventh-century Arabia, where young girls were buried alive for being perceived as a curse, giving women the right to inheritance was seen as a radical act, which according to Barlas, must be viewed in such a context.

As much as the book criticises patriarchal understandings of Islam, Barlas had also targeted secular feminist accounts, balancing her analysis. She also compares the word of God in the Quran with Christian and Jewish texts, comparing and contrasting perceptions of what God means to all three Abrahamic faiths and an analysis of the impact of Islam departing from the earlier religions.

|

|

God is no man

One of the main points Barlas emphasises is that God in Islam has no gender, therefore by default, Islam in its essence is not an androcentric religion.

She emphasises that the names of God in the Quran are all gender neutral and draws upon contemporary translations of the Quran which use androcentric translations of "God", such as "Lord".

"It is thus all the more troubling when we translate these terms (Allah, Rabb) as 'king' or 'lord' which are not only androcentric, but which also fail to convey the sense of creatorship and sovereignty implicit in terms like Rabb and Allah," she said in a chapter focused specifically on the imaginary patriarchy behind the common ontology used when addressing God.

"In fact, words like king and lord encourage false analogies between God's sovereignty and man's, even though the two are wholly different."

The perception of God through an androcentric ontology despite the Quran describing a God without gender, Barlas argues, is the product of patriarchy that existed before Islam.

Man's not the word

The book consistently emphasises that a family's father/male figure is not the head of the household in Islam and they aren't given the luxury of obedience. The Quran calls for respect for both parents, but there are instances in the Quran in which children have disobeyed their parents when they are told to go against God, thus limiting parental authority.

Barlas highlights parts of the Quran that warn how people following the traditions and words of their fathers led people to reject God.

The story of Abraham and the almost-sacrifice of his son was mentioned consistently throughout the work. Barlas highlights that in the Muslim version of the story, Abraham did not go ahead with intending to sacrifice his son until his son gave his own consent to "submitting to the will of God". For Barlas, the way the story is narrated in the Quran, where vocal consent was pivotal to Abraham going ahead with the sacrifice shows the word of the father is not sovereign.

The 'pure woman'

Twitter Post

|

Shaming women in Islam, according to Barlas, does not come from the Quran itself.

Themes in Islam which are often criticised as being used to subjugate only women, such as "modesty", Barlas argues, come from ethics prescribed to both women and men. God orders both women and men to dress modestly, God tells both women and men to restrict sexual relations until marriage.

Under her analysis, Islam doesn't shame women into being sexually submissive, nor does it "distinguish between female and male sexual natures" or denies that women have a right to fulfil their desires.

Chasity in Islam, evident from the Prophet Mohammed marrying widowed and divorced women, is not based on whether a woman has had sexual relations in the past, but based on a genderless universal standard as to whether a woman or man has had sexual relations outside the permissible realm of marriage.

Heteronormativity

The book heavily focused on heteronormative gender relations in Islam, and did not mention the role of Muslims in the LGBTQ+ community. While the book does not speak out against LGBTQ+ Muslims, or implies they have no direct Islamic role, it remains a heteronormative book focusing specifically on CIS-gendered relations.

Even when addressing women's role in Islam, there were times in which Barlas makes technically correct statements, such as the Quran not explicitly forbidding women to marry non-Muslim men, but failed to elaborate and contextualise her argument by analysing the Quranic verses in question.

Academic yet accessible

Believing Women in Islam was a refreshing read, in which Barlas achieved in answering many important questions asked by Muslim women. It looks at the epistemology that the Quran is widely interpreted with, questioning the validity of "orthodox" readings, which add emphasis on content by stripping verses of the Quran from the historical context surrounding the time of its revelation.

It also criticises secular feminists, maintaining that the work, while discussing the role of women in Islam and women's rights, is not in itself a "feminist text", making it a unique analysis that underscores the exclusively the role of women in Islam.

Holding her argument while balancing a range of counter-arguments, not just focusing on either secular feminism or those with an androcentric epistemology, gives her book a strong academic holding. The style of writing, however, also helped her book maintain an accessible nature, suitable for even those whose understanding of women in Islam is yet to be fully nourished.

Follow Diana Alghoul on Twitter: @SuperKnafeh

The New Arab Book Club: Click on our Special Contents tab to read more book reviews and interviews with authors: