HRW: Egypt's stricter anti-FGM penalties step towards elimination

Egypt’s new harsh penalties against those involved in Female Genital Mutilation are a step towards elimination, Human Rights Watch said on Friday, however more reform is needed to shift society’s perspective on the “horrific practice”.

The latest anti-FGM move is a step in the right direction but further reforms are needed to wipe out the controversial procedure, the global rights group said in a statement.

In late August, Egyptian parliament approved stricter penalties, including increasing prison terms of five to seven years for those who carry out FGM and up to 15 years if the case results in permanent disability or death.

“Stricter penalties for female genital mutilation in Egypt now reflect the horrific and potentially deadly consequences of this discriminatory practice,” said Rothna Begum, Middle East women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch.

“But broader law reform is needed to adequately combat this horrific practice, and all such laws should be enforced to protect tens of thousands of girls at risk.”

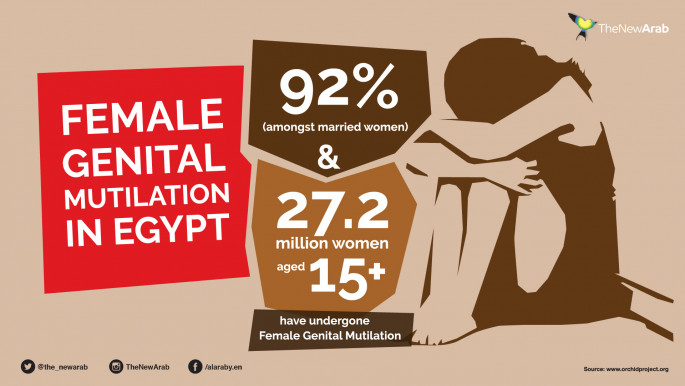

Despite a 27 percent drop in FGM among Egypt’s females in the past 30 years, some 92 percent of married Egyptian women between the ages of 15-49 had undergone the procedure, according to a 2014 survey conducted by the Ministry of Health and Population.

Figures also show a shockingly large majority support the seemingly archaic practice – with many believing it guarantees purity and chastity by quelling girls' sexual desires, making them, as they claim, more attractive for marriage.

In 2010, a UNICEF report recommended that “[t]he law should take into account the hardship inflicted on families when parents are penalised and should consider the best interests of the child. Preventive and protective measures should be prioritised and punishment should be a last resort.”

Human Rights Watch reiterated the sentiments, suggesting authorities should “enact legislation to guarantee funding and other resources for a comprehensive response, including prevention programs aimed at changing social attitudes that condone the practice.”

The United Nations is working to end the practice of cutting women's genitalia by the target date of 2030, a goal set in its new development agenda that was adopted in September by all UN member-states.

![FGM Egypt [LightRocket] FGM Egypt [LightRocket]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/media/images/279DE52B-0F1F-4E17-9678-25A6C79933AB.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=KV_yEB3p)

![Thousands gather in front of the Cannon House Office Building and the US Capitol to demand the US pressure Israel on a ceasefire in its conflict with Gaza. [Brooke Anderson/The New Arab]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_330x185/public/2023-10/393387495_710301464290105_8375393679399060035_n.jpg?h=ff8c3fa3&itok=WdtyAWP_)