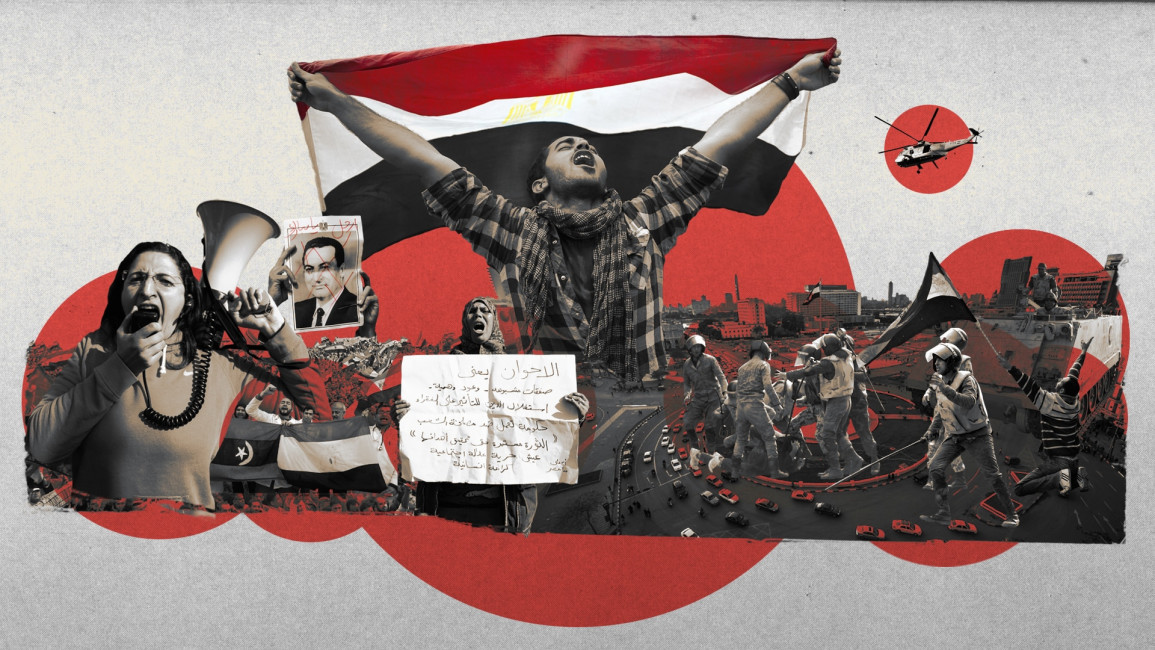

A decade of Arab protest caps a century of erratic statehood: Part I

Only Tunisia has transitioned to a constitutional democracy, and Sudan is in the midst of a fragile three-year transition. Major national protests still define Lebanon, Sudan, Iraq, and Algeria, while Libya, Syria, Iraq, Yemen suffer serious warfare among local and foreign forces. Most other Arab countries have reverted to tighter autocratic rule that weakens personal liberties.

This conventional view of the Arab region after a decade of protests is incomplete, though. A more thorough analysis would recognise that major changes that will impact future governance continue to occur across the region. Ten years is not sufficient time to credibly assess these Arab revolutionary uprisings - "uprisings" because they are spontaneous civil protests, and "revolutionary" because they aim to totally change governance systems and citizen-state relations, including the values and actions of individual citizens.

To begin, it's important to grasp two time frames which led up to the Arab uprising: First, the 50 years since 1970 during which military rulers who seized power across the region used oil wealth to institutionalise mostly corrupt and inefficient autocratic systems; and second, the 100 years since WWI that gave birth to the modern Arab state system which has largely experienced erratic statehood and weak sovereignty, especially in recent decades.

|

The Arab uprisings are part of the long-denied process of national self-determination and state-building that Arab citizens yearn for |  |

In their breadth, depth, longevity, demands, and political action, the Arab uprisings are part of the long-denied process of national self-determination and state-building that Arab citizens yearn for, and now try to seize - with mixed results - in this early stage of collective street action.

New alliances and aspirations: The people as political actors

This decade of uprisings is historically significant for several unique aspects that the region had never experienced on such a large and sustained scale. The most striking is their continuity. Protests against state rule have occurred since 2010 in half the 22 Arab League countries, including some monarchies and oil-rich states. The regional spread is matched by the nationwide grievances of a majority of citizens within individual countries.

This was evident in Lebanon, Algeria, Iraq, and Sudan recently, where different sectarian, ethnic, ideological, and regional groups that occasionally had protested separately have now joined in single and coordinated national protests. They have learned that they all suffer the same stresses and inequities - few jobs, low pay, poor education and health services, rising inflation and poverty, imploding economies, unchecked corruption, and a general culture of uncaring and/or incompetent officials.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

The common concerns of the protesters who seek a totally new government system are evident in the identical demands they raise in each country. Unlike the spontaneous 2010 protests that called for broad notions of dignity and social justice, today's demands all seek a series of specific transformative steps to create more efficient, democratic, and accountable governments under the rule of law. They include: the resignation of all senior ruling officials, a transitional government to hold new parliamentary and presidential elections, a new constitution that guarantees citizen rights, an independent judiciary and anti-corruption mechanisms, and putting on trial former officials who ravaged the society and economy and grew wealthy in the process.

The current protests are striking also for bringing together different groups with a wide range of grievances that they had formerly raised separately, and almost always unsuccessfully. Environmentalists, activists for social justice, gender and minority rights, and democratic rule-of-law, and others joined hands for months on end to lobby for governance that would treat them all equitably.

|

Activist citizens also created new organisations to replace moribund and corrupted state institutions |  |

Individuals and organised groups worked together in public squares to express their grievances and chart out solutions for the new states they sought to build. This generated two important new phenomena: many people who never expressed themselves in public joined the protests and became political actors (such as schoolchildren, teachers, and residents of remote provinces); and, most of them for the first time in their lives experienced contributing to shaping their anticipated new government and new national policies.

Activist citizens also created new organisations to replace moribund and corrupted state institutions, such as media organisations, professional unions, and self-help community centres.

Alongside these and other signs of the slow birth of a new Arab citizen, however, the last few years have also seen the brutal response of regimes and sectarian groups that refuse to share or relinquish power. Everywhere - in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Algeria, Sudan, Morocco, and others - long-entrenched regimes reacted to the initial uprisings with promises of limited reforms, including a new prime minister, new elections, or more social spending.

Twitter Post

|

Protesters rejected these as insulting sops that perpetuated the power structure and its failed policies, and they continued demonstrating to bring down the entire government. The power elite and its sectarian thugs and militias then reacted with brutal political or military force. They shot and killed hundreds of demonstrators, jailed or indicted protest leaders, burned down protest camps, and allowed moribund economies to whither even more, which drove more families into poverty and desperation.

Read more: Obama's memoir and the Arab Spring: America's missed opportunity to help democracy take hold

The state's harsh responses did not quell the protests - but the coronavirus in March 2020, did. For most of 2020, simmering citizen anger and fear failed to force new state policies, as the public pressure of the street protests dissipated.

As the virus-induced economic slowdowns and health concerns eventually halted most protests, some governments tried to use their coronavirus responses to generate new legitimacy among former supporters who had often joined the protests, and who saw their own life prospects shrivel by the month.

Protesters across the Arab region are on hiatus today, awaiting the end of the coronavirus threat and using the time to reassess their strategies, strengths, and weaknesses, so that they are better prepared when the political protests resume - which they will, in some forms we may not grasp today.

Rami G. Khouri is Director of Global Engagement and senior public policy fellow at the American University of Beirut, and a non-resident senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Follow him on Twitter: @ramikhouri

Have questions or comments? Email us at editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.