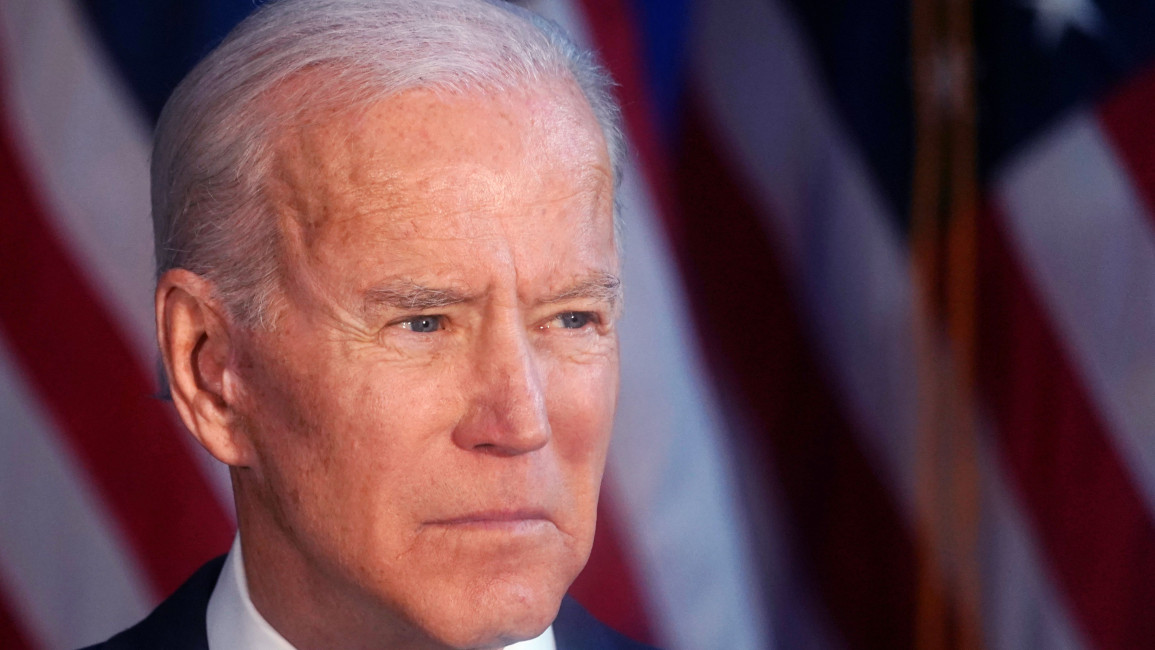

Biden’s first year in foreign policy was a master class in continuity

The Biden administration’s foreign policy in its first year was mostly defined by an unwillingness to make major policy changes and to take significant political risks to follow through on the president’s campaign pledges.

The important exception, of course, was Biden’s prudent decision to withdraw US forces from Afghanistan, which stands out even more as one of the few occasions when the president has bucked the prevailing consensus view in Washington. On almost every other issue, however, the Biden administration has been overly cautious and content to accept the status quo, even when it was a Trump-era policy that the president and his officials had condemned as an obvious failure.

From tariffs to “maximum pressure” sanctions to arms sales to reckless clients, the watchword for the last year has been continuity.

There has been a sharp increase in emphasising support for human rights in administration rhetoric since Trump left office, but one looks in vain for examples of how Biden has made human rights central to his foreign policy. This has been most noticeable in the resumption of weapons sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates while their war on Yemen continues unabated.

"No one expected that Biden was going to preside over a radical overhaul of US foreign policy, but even when measured against a much more modest standard, his foreign policy has fallen short of what his supporters reasonably expected to see"

Despite credible charges that the Saudi and Emirati governments have used US-made weapons to commit war crimes against civilians, the Biden administration has approved new weapons and maintenance contracts for the Saudi military and allowed the $23 billion arms sale to the UAE to go forward. Now that the UAE is losing interest in sale because it comes with too many security restrictions, the decision to allow the sale to proceed looks even worse.

No one expected that Biden was going to preside over a radical overhaul of US foreign policy, but even when measured against a much more modest standard, his foreign policy has fallen short of what his supporters reasonably expected to see. On Yemen, the president made some encouraging early moves that suggested that his administration was serious about changing course, but as the year dragged on and Yemen’s suffering deepened it became clear that the change to US policy was minimal.

There has been scant pressure on the Saudi coalition to end the killing blockade, and the US is providing the Saudi military with more missiles that it can use to enforce that blockade from the air. It was never likely that Biden was going to treat Saudi Arabia as a “pariah,” but the accountability that Biden promised has never materialised.

Analysis: The New Arab’s Brooke Anderson digs into the implications of Biden’s hasty withdrawal on American alliances. @Brookethenews https://t.co/XjKmihIfXY

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) August 30, 2021

The Trump administration’s use of economic warfare to inflict punishment on entire countries was one policy that was crying out for immediate changes, but this is also one that Biden has done the least to alter. Broad sanctions on Venezuela, Iran, Syria, and North Korea all remain in place, and there has been no urgency to lift any of them despite their harmful effects on the population in the middle of a pandemic.

The Biden administration’s lengthy review of sanctions policy was remarkable for how little the administration had to show for nine months of effort. Following the Taliban takeover earlier this year, Afghanistan is now being subjected to the destructive effects of the same kind of economic warfare that the US has been waging on other countries for years. The unfolding humanitarian nightmare there now threatens tens of millions of lives unless the administration moves quickly to make the necessary changes in US policies.

The administration’s refusal to offer even token sanctions relief for humanitarian purposes has been one of the main sticking points in the talks to salvage the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Because Iran has continued reducing its compliance with the nuclear deal to protest the “maximum pressure” sanctions and sabotage attacks on its programme, the Biden administration will not budge on sanctions relief until Iran returns to full compliance.

This has created an unfortunate test of wills where neither government wants to take the first step to break the impasse, and the result is that the JCPOA is slowly being extinguished while a mutually beneficial solution stares everyone in the face.

Having missed the window for a quick restoration of the deal before Iran’s presidential election in June, the Biden administration has begun suggesting that it is already looking for the exits from the talks and has started floating a series of bad “options” if the talks fail.

For an administration that touted its own diplomatic skills and boasted that “diplomacy is back,” the failure to re-enter and salvage the JCPOA is probably the biggest and most consequential disappointment of the year. There is still a possibility that the talks might prove more productive in 2022, but without some meaningful concession from the US on sanctions relief it doesn’t seem promising.

Arms control was one area where there were at least a few bright spots. Biden extended New START at the beginning of the year and saved the last remaining arms control treaty with Russia. US-Russian strategic stability talks commenced later in the year after Biden’s summit meeting with Putin, and initial reports suggested that the talks had been productive in laying the foundations for further discussions.

"If the Biden administration’s second year is going to be more successful than its first, it will need to take more risks and accept more short-term criticism to advance US interests abroad"

Unfortunately, Biden made no effort to revive Open Skies, and the current crisis over Ukraine makes it unlikely that there will be significant progress on new arms control agreements in the foreseeable future.

Biden does deserve a lot of credit for completing the withdrawal from Afghanistan in the face of intense resistance and extremely negative media coverage. In sharp contrast to the rest of his foreign policy decisions this year, Biden recognised what had to happen, he understood what was in the best interests of the country, and he followed through on the decision when it would have been easier politically to cave to his critics.

While it isn’t true that the US is no longer at war, the president ended the US military presence in Afghanistan when allowing it to drag on interminably would have saved him from months of criticism.

If the Biden administration’s second year is going to be more successful than its first, it will need to take more risks and accept more short-term criticism to advance US interests abroad. Engaging with Russia to defuse the crisis over Ukraine will be controversial in Washington and in some allied capitals, but it is necessary to reduce tensions and avoid worse outcomes.

Pressuring Saudi Arabia to end the blockade of Yemen will provoke more complaints from hawks in Congress, but it is what needs to happen if the US is to help end the misery that our government’s support for the war has caused for the last six and a half years.

The administration also needs to take a much harder look at the policies that it inherited from Trump. If they understand that “maximum pressure” sanctions have been a cruel failure across the board, they should lift or suspend those sanctions to the greatest extent possible.

What the Biden administration must not do is simply maintain Trump-era policies for the next three years because they are afraid of the political backlash from hawks that are going to attack them in the harshest terms no matter what they do.

Daniel Larison is a contributing editor at Antiwar.com and former senior editor at The American Conservative magazine. He has a Ph.D. in History from the University of Chicago.

Follow him on Twitter @DanielLarison

This article was originally published on Responsible Statecraft.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.