China-Arab relations in the time of Trump

Arab governments have refrained from condemning Trump's mounting politic on - and often against - the global Arab and Muslim communities, though Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi has broken ranks to express resounding support for Trump, much to the chagrin of international observers.

Meanwhile, Trump's proto-administration has already floated a Muslim registry at home and barring Muslims abroad. Trump now plans to install what some have called a "reckless" hardliner as the US ambassador to Israel - and in Jerusalem, not Tel Aviv.

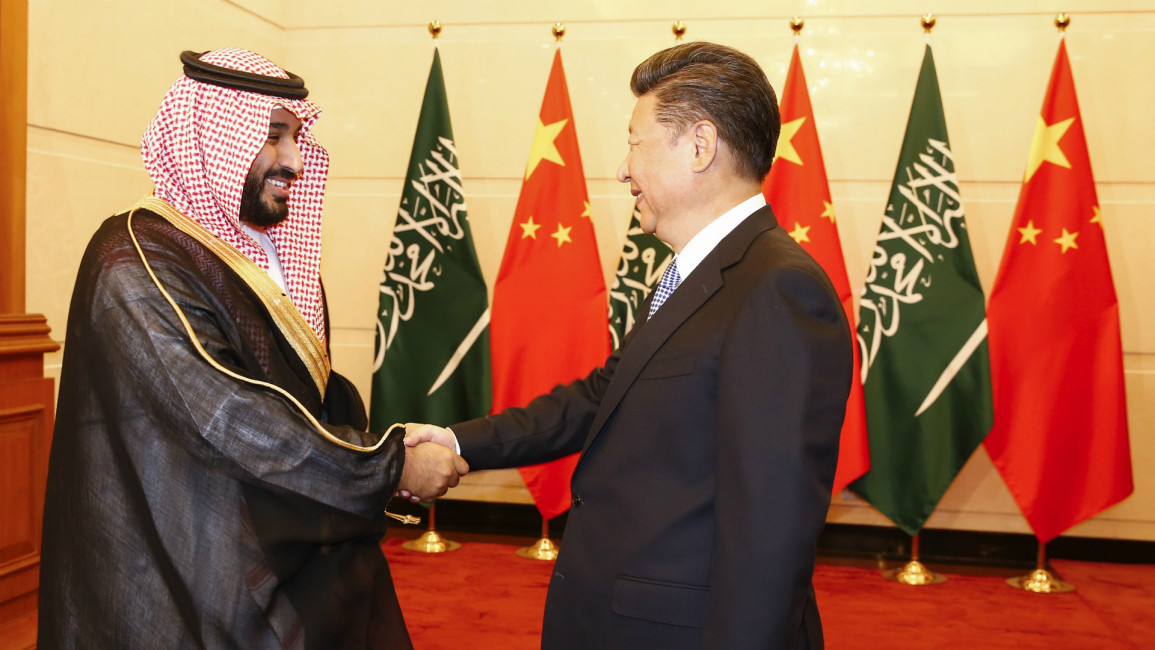

Mounting concern over the pending Trump campaign's Arab and Muslim affairs policies highlight Arab gestures in recent years to nurture relations with an emerging alternative - China, which by some measures has already surpassed the US as the world's largest economy.

|

With heightened anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment in the US, Arab nations having nurtured ties with China in recent years may prove not just fruitful but necessary |  |

China's rise has reverberated within the Arab World. In just the past decade, China surpassed the US as the leading trade partner in several Arab countries, including Washington's key regional ally, Saudi Arabia.

It appears now, with heightened anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment in the US, Arab nations having nurtured ties with China in recent years may prove not just fruitful but necessary.

The problem then becomes, for Arab nations, envisioning what closer alignment with the People's Republic looks like; recent developments show that an Eastward-facing Arab World would have many of the same concerns as when it was tied by energy trade and counter-terrorism efforts to the US.

China - as the People's Republic, not the age-old civilisation - is just shy of 70 years old; the nation as an economic and political country of scale is even younger. As Beijing finds its way as a debutante big-league diplomatic player, it appears it is beginning to crib heavily from the pre-Trump US model of engagement with the Arab World.

China has long positioned itself as an alternative to the US model of development and foreign relations, but it has also in recent years premised much of its relationship to the Arab World on oil and gas trade, counterterrorism and tourism. And it has, more recently, begun to involve itself in Middle East political affairs - from the Palestine-Israel conflict to the destruction devastating Syria - despite its long-championed policy of non-interference.

China in October conducted joint counterterrorism drills with Saudi Arabia; it has been doing the same with other Muslim-majority nations in Central and South Asia, amid mounting concern over China's beleaguered Uyghur ethnic minority. The October drill with Riyadh, conducted in the southern Chinese city of Chongqing, was the first instance of China engaging the Arab World as the US and European Union had - over the so-called "War on Terror".

That same month, China, at an annual meeting with GCC countries that played to much less fanfare in Chinese and Arab presses than in previous years, said that Arab countries must "restructure their economies" away from the very thing they were there to discuss: the energy industry.

Despite a wavering oil market, Chinese diplomats have focused their attentions on trade meetings with the GCC's top players. Earlier this month, for instance, Chinese diplomats met with Omani counterparts in Muscat to "consolidate" trade with the Gulf sultanate - nowhere in the press on the issue was any mention of gestures to diversify trade.

In recent years, 90 percent of Oman's exports to the People's Republic have been fuels, according to statistics from the World Bank. And in recent years that demand has surged. China is Oman's largest buyer of crude oil and other fuels, with about half of the nation's entire export market going to the People's Republic annually.

Often, in press releases and speeches on growing economic and political relations between China and Arab states, there are declarations that Beijing will explore alternatives to the energy-centric model in its relationship to the Middle East. It's now been decades, though, that Beijing has been promising to find new, unexplored ways of establishing a footprint - new markets, new collaborations - in the Arab World.

Even beyond the oil and gas-exporting Middle East, China is still deeply reliant on the energy industry in overtures to the Arab World.

China made a landmark foray into Morocco this year. Previously, Beijing had a modest portfolio in the North African kingdom, focusing instead on neighbouring Algeria, the main regional energy-exporter.

In May, Moroccan King Mohammed VI visited Beijing, where he penned deals with Chinese officials to include waiving visa requirements for Chinese nationals. North Africa tourism is already popular in the People's Republic, but this move will likely draw more Chinese tourists to Morocco's already dominant, oft-wavering tourism sector, which had previously been dominated by Westerners.

Beyond tourism, the diplomatic meeting would also result in a Chinese-led project to build the world's largest solar power facility in the Moroccan desert. Even in a country where the leading natural resource is phosphate - not crude - Beijing has bolstered developments in the field of fuels.

And yet the powers that be in Beijing have been ostensibly committed to establishing an innovative foothold with its partners.

The administration of Chinese President Xi Jinping, in a bid to strengthen ties along the "Silk Road Economic Belt", announced a 2013 measure called the One Belt, One Road (一带一路/ Yi Dai Yi Lu) programme that pledged to pump up to $8 billion into infrastructure and investment developments with partners across continental Asia, to include the Middle East.

But the programme has struggled, analysts say, and may have only been a pretext to export China's overcapacity construction and production sectors.

What's certain is that the push has done little so far to revolutionise the outside world's traditional talking points with the Arab World on energy, tourism and, per the October collaboration with Riyadh, "terror".

A late 2015 position paper on the One Belt, One Road initiative from Beijing's influential State Information Centre think-tank suggested a Free Trade Agreement with the GCC. But instead of proposing any revolutionary new kind of trade, it focused entirely on the energy industry, saying that while the North American shale boom had rocked the market, "the Gulf states remain the heart of the world's future energy supply".

Underlining an increasingly Washingtonian style of diplomacy, Beijing has in recent years tried on numerous occasions - and playing to great scepticism - to elbow its way into mediating tensions between Palestinians and Tel Aviv. More recently, Beijing has even taken sides in mounting conflagrations in and surrounding Yemen.

The support made more prescient an annual Chinese naval mission to the Gulf of Aden this month. China has sent missions to the Gulf since 2008, and they are typically billed as anti-piracy measures.

China has also repeatedly worked with Russia to halt UN resolutions on the crisis in Syria.

China's relationship with the Arab World has in the past sought, at least ostensibly, to differentiate itself from the US model. The union was once premised, at least in words, on a decolonial ethic - an East arising in solidarity to reconfigure the prevailing world order and the very nature of diplomacy and trade.

China redoubled efforts to breathe life into its Arab World policy in 2001, at a time when US and Western backlash over the September 11 attacks took aim at Arabs, Muslims and their business.

Months after the attacks, Beijing founded the Chinese-Arab Friendship Association to help promote ties with the Arab World. As trade began to grow semingly exponentially, Beijing built soft power in the Middle East and North Africa.

At one point, this iterated itself in Chinese-built mosques and other Islamic infrastructure across the greater continent of Asia. China used state-owned funds to build a mosque in Guangzhou at the site of what is believed to be the grave of a close relative and companion of the Prophet Mohammed to welcome Arab and other Muslim-majority nations in the west of Asia to the 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games.

It is technically unconstitutional for the Chinese state to participate in building religious facilities - but Beijing prides itself on the kind of institutional flexibility that allowed the country to rebound rather quickly from the 2008 Great Recession.

In Algeria, Chinese state-owned enterprises embarked on a bid to build the third-largest mosque in the world, after those in Mecca and Medina. In Saudi Arabia, a state-owned company built a light rail between Mecca and Medina - the Haramain High Speed Rail Project - to help offset congestion by crowds of visitors on Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages.

|

Many of China's post-9/11 inroads into the Arab World were plagued with a series of setbacks and upsets |  |

At a time when momentum had been building for the China-Arab partnership, there was hope that the China model of rapid-fire development could inspire a similar - albeit more labour-rights-oriented - push in the Arab World, particularly non-GCC economies dependent on tourism and the West's disposable economies.

But many of China's post-9/11 inroads into the Arab World were plagued with a series of setbacks and upsets.

In Algeria, there were a few examples. A bid to build the longest highway in Africa left local Algerian contracted workers without pay for over a year, driving many into poverty and provoking the ire of the nation's stalwart trade unions. China has a single formal - government-approved - union.

The highway - which Algerian media have complained was already crumbling in parts - has also been subject to lengthy trials on allegations of corruption.

Algeria's massive Chinese-built mosque project - with costs skyrocketing to more than a billion dollars - has been repeatedly delayed, and will now be completed years behind schedule; for reasons that remain unclear, responsibility for the project changed hands in 2015, from the Ministry of Religious Affairs to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

In Saudi Arabia, the Haramain railway has long delayed opening, with Saudi media reporting anger at officials for mishandling their response to the severe flooding of a portion of the track earlier this year.

China and its Arab partners have faced larger unforeseen transactional costs. In addition to the loss of human life and all manners of destruction suffered by the Arab World, heightened tumult in the region that began with the 2011 revolutions also cost Beijing a great deal in countries such as Syria and Libya, where China had penned scores of high-stakes deals that the chaos had suddenly pushed into limbo.

Middle East observers were flustered by outgoing US President Barack Obama's so-called Pivot to Asia insofar as it indicated Washington's divestment from the Middle East - after the US, among other things, launched a war that obliterated much of Iraq, the aftershocks of which are still very much present.

Now the Arab World may find itself weighing its own pivot, forcing it to consider both its recent roadblocks with China and what it should and shouldn't replicate from its relationship to the US.

Massoud Hayoum is a freelance journalist and analyst who has reported for Al Jazeera America, The Atlantic, AFP and the South China Morning Post.

Follow him on Twitter: @mhayoun

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.