Clinton: A return to interventionism in the Middle East?

Clinton: A return to interventionism in the Middle East?

Comment: When it comes to foreign policy, Hillary is all about following the Washington playbook, writes Sylvain Cypel.

7 min read

Hillary is running a classical campaign representing the dominant current of American politics [Getty]

In the first of a two-part commentary, Sylvain Cypel explores the implications of a Clinton presdiency for the Middle East.

Back in mid-January 2011, the Obama administration was engaged in a deep and pressing debate. For two weeks there had been a growing throng of protesters in Cairo's Tahrir Square, demanding the resignation of then President Hosni Mubarak.

In the White House, Obama's national security aides, Samantha Powers, Ben Rhodes and Denis McDonough, were urging the US president to give his public support to the forces of change.

But - as the columnist James Traub points out - for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, this attitude of foreign policy intervention in matters of human rights was naive. Later, most of those same aides favoured American armed action in Syria.

Close to Mubarak and even closer to his wife, Clinton worried most about the troubled signal the fall of the Mubarak regime might send to American allies in the region: Israel (whose Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu voiced unconditional support for Mubarak) as well as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf emirates.

She used the January 28 episode of Meet the Press to publicly declare that only Mubarak could lead an "orderly, peaceful transition to real democracy".

She could count on the support of two powerful government figures on this point: Republican Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Vice-President Joe Biden. However, Barack Obama eventually decided to contradict her, and the day after Clinton's televised declaration, he publicly appealed for an immediate transition to democracy. Ten days later, under the pressure of public rebellion, Mubarak stepped down.

A conservative among the Democrats

Hillary Clinton, the woman who thought she could stop the course of time, is the Democratic candidate for the American presidency. Every current poll indicates she's in a strong position to become the next president, at a time when the outside world appears to Americans more dangerous, chaotic and incomprehensible than ever.

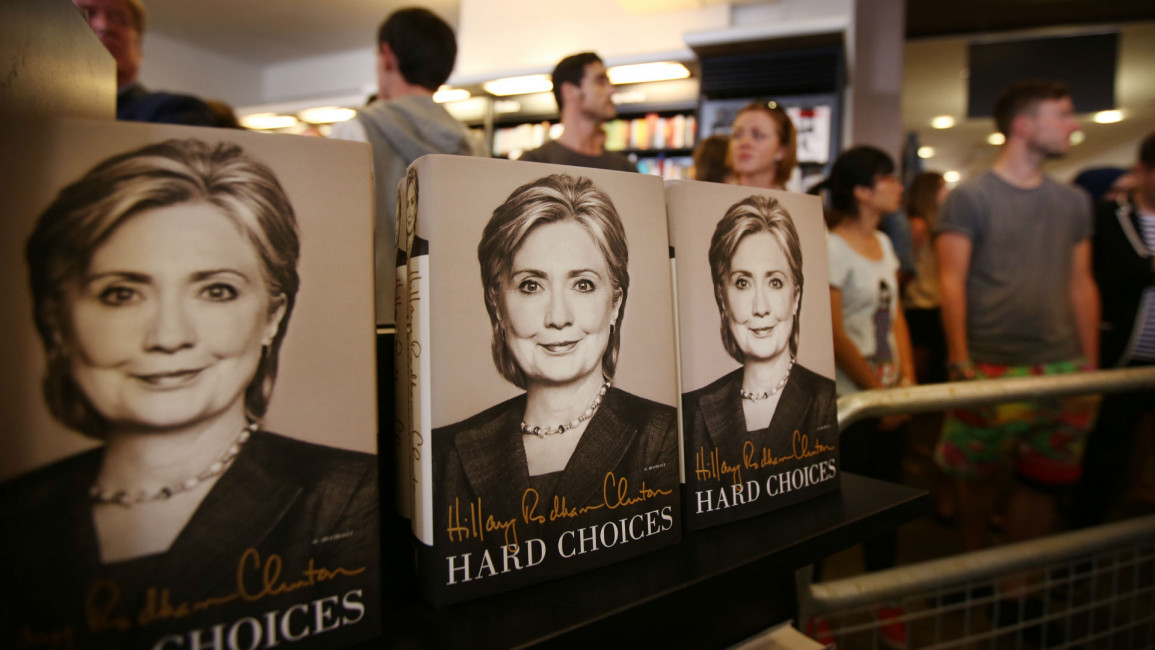

Is her conduct during the opening days of the Arab Spring in Egypt an indication of things to come regarding her policy in the Middle East once she gets elected? In her memoirs, Hard Choices, Clinton clearly states that the outcome of the Egyptian Spring proved her right: The fall of Mubarak paved the way to a harsher dictatorship than his.

She also refutes the idea that his withdrawal was inevitable.

Hillary Clinton's position may have resulted from imperfect information fed to her by her diplomatic services in place in Egypt. But, as regards the heart of the debate raging in the White House at the time, she appeared as the proponent of the more conservative line, in terms of both risk-taking and political engagement.

This conservatism - some go as far as calling it neoconservatism - constitutes the bulk of left-wing liberals' attacks against her. In a major article written in April 2016, US foreign affairs correspondent Jeff Goldberg described Barack Obama's contempt for followers of the Washington playbook - that unofficial guide adhered to by the majority of Washington's foreign affairs elite, but of which Obama himself is highly distrustful.

His main point of contention is the over-reliance on force that the guide prescribes in cases of conflict, favouring diplomatic pressure over compromise, resorting to coercion and active arms use only if necessary.

Hillary Clinton is thoroughly part of this establishment where the "military-industrial complex" can meet easily with the Council on Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies and many other think tanks, building easy and influential access to the administration.

The world's police?

Economist Jeffrey Sachs defined Hillary Clinton's fundamental traits in a recent article by explaining that she was "drunk on American power". Each time a vote about the use of military force came up in the Senate she voted yes: against Milosevic in Serbia in 1999, against Saddam Hussein in 2003, against Gaddafi in 2011 and against Bashar al-Assad in 2012-2013.

The consequences were disastrous, at least in the cases of Libya and Iraq.

Secondly, she's full of the idea that "America and America only must rule the world" and of the arrogance that comes with American exceptionalism. The journalist-turned-environmentalist sums it up: "Clinton accuses Trump of being unpredictable but she, on the other hand, is dangerously predictable." He fears that once Clinton becomes president, the United States will revert to a classical vision of foreign policy, as laid out in the Washington playbook.

James Traub is more moderate but basically agrees. "Hillary Clinton's political agenda does not fundamentally differ from Obama's but the way she views international relations resembles that of Kissinger," he writes - that is to say she sees the world through the lens of political "realism".

For Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, a politics professor at the University of Northwestern near Chicago, Hillary Clinton in the White House might mean new American wars in the Middle East. She thinks that Clinton was never able to "acknowledge the limits of the capacity of the United States to transform the world according to their interests and image". She didn't learn the lessons from her positions on Iraq (as a Democrat Senator she voted in favour of the war declared by George W Bush in 2003) or on Libya.

Her policy in Libya - for which she worked to convince the reluctant administration to start the Benghazi operation -with deadly results - shows how subservient she is to the Washington playbook. Hurd reminds us of the words of warning from Vice President Joe Biden - hostile to US participation in toppling Gaddafi - concerning "not the day after but the decade after" the beginning of a war.

A narrow view of US interests

A quick review of Clinton's attitude during her years as secretary of state (2009-2013) reveals a woman overcome with a narrow vision of American interest, someone who "believes in the exemplary value of a threat more than its actual power", Traub writes. That's why she vehemently criticised President Obama when he failed to follow through on his threat to bomb Syria in August 2013 after Damascus started using chemical weapons, thus crossing the red line his administration had drawn.

According to sources close to her, Clinton reacted violently: "If you say you're going to strike, you don't have a choice: you must do it." For Obama, airstrikes would have achieved nothing except saving face, and would probably have worsened the Syrian tragedy - if such a thing were even possible.

It wasn't the first time that Obama and his secretary of state disagreed. Their first dispute came in 2009 over Afghanistan. American generals on the ground demanded 40,000 extra soldiers, which Obama was reluctant to deliver while Clinton enthusiastically supported the generals' anti-insurgency plan.

In her memoirs, she explains how the Taliban would never agree to negotiate as long as they remained in a position of force. Her plan was to defeat them or weaken them sufficiently to be able to plan ahead. As always, here was the Washington playbook in action once again.

"In retrospect, the generals wildly overestimated America's capacity to make Afghanistan self-sustaining, either militarily or politically. Obama's instincts were right, as they had been in Iraq. Clinton was wrong - as she had been in Iraq," writes Traub.

Her attitude towards Tehran when negotiating the end of its nuclear weapons programme was characterised by marked scepticism and a flair for creating obstacles on the way to the agreement. In her memoirs, she remains supportive of the nuclear deal but shifts focus onto the key role played by the many sanctions put in place to get Tehran to concede.

For Obama, sanctions were always less important than diplomacy and concessions in reaching a final agreement.

Obama, continues Traub, "was willing to help Iran save face, because he understood the need for that. He understands that they also have politics and a history, and therefore he's sceptical that they'll just give in because we talk tough".

Once again, while Obama was shaking off the Washington playbook, Clinton continued to follow its rules.

Sylvain Cypel, a former correspondent for Le Monde, is the author of 'Walled: Israeli Society at an Impasse.'

Back in mid-January 2011, the Obama administration was engaged in a deep and pressing debate. For two weeks there had been a growing throng of protesters in Cairo's Tahrir Square, demanding the resignation of then President Hosni Mubarak.

In the White House, Obama's national security aides, Samantha Powers, Ben Rhodes and Denis McDonough, were urging the US president to give his public support to the forces of change.

But - as the columnist James Traub points out - for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, this attitude of foreign policy intervention in matters of human rights was naive. Later, most of those same aides favoured American armed action in Syria.

Close to Mubarak and even closer to his wife, Clinton worried most about the troubled signal the fall of the Mubarak regime might send to American allies in the region: Israel (whose Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu voiced unconditional support for Mubarak) as well as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf emirates.

She used the January 28 episode of Meet the Press to publicly declare that only Mubarak could lead an "orderly, peaceful transition to real democracy".

She could count on the support of two powerful government figures on this point: Republican Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Vice-President Joe Biden. However, Barack Obama eventually decided to contradict her, and the day after Clinton's televised declaration, he publicly appealed for an immediate transition to democracy. Ten days later, under the pressure of public rebellion, Mubarak stepped down.

A conservative among the Democrats

Hillary Clinton, the woman who thought she could stop the course of time, is the Democratic candidate for the American presidency. Every current poll indicates she's in a strong position to become the next president, at a time when the outside world appears to Americans more dangerous, chaotic and incomprehensible than ever.

Is her conduct during the opening days of the Arab Spring in Egypt an indication of things to come regarding her policy in the Middle East once she gets elected? In her memoirs, Hard Choices, Clinton clearly states that the outcome of the Egyptian Spring proved her right: The fall of Mubarak paved the way to a harsher dictatorship than his.

She also refutes the idea that his withdrawal was inevitable.

Hillary Clinton's position may have resulted from imperfect information fed to her by her diplomatic services in place in Egypt. But, as regards the heart of the debate raging in the White House at the time, she appeared as the proponent of the more conservative line, in terms of both risk-taking and political engagement.

This conservatism - some go as far as calling it neoconservatism - constitutes the bulk of left-wing liberals' attacks against her. In a major article written in April 2016, US foreign affairs correspondent Jeff Goldberg described Barack Obama's contempt for followers of the Washington playbook - that unofficial guide adhered to by the majority of Washington's foreign affairs elite, but of which Obama himself is highly distrustful.

His main point of contention is the over-reliance on force that the guide prescribes in cases of conflict, favouring diplomatic pressure over compromise, resorting to coercion and active arms use only if necessary.

Hillary Clinton is thoroughly part of this establishment where the "military-industrial complex" can meet easily with the Council on Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies and many other think tanks, building easy and influential access to the administration.

|

[Clinton is] full of the idea that 'America and America only must rule the world' and of the arrogance that comes with American exceptionalism |  |

The world's police?

Economist Jeffrey Sachs defined Hillary Clinton's fundamental traits in a recent article by explaining that she was "drunk on American power". Each time a vote about the use of military force came up in the Senate she voted yes: against Milosevic in Serbia in 1999, against Saddam Hussein in 2003, against Gaddafi in 2011 and against Bashar al-Assad in 2012-2013.

The consequences were disastrous, at least in the cases of Libya and Iraq.

Secondly, she's full of the idea that "America and America only must rule the world" and of the arrogance that comes with American exceptionalism. The journalist-turned-environmentalist sums it up: "Clinton accuses Trump of being unpredictable but she, on the other hand, is dangerously predictable." He fears that once Clinton becomes president, the United States will revert to a classical vision of foreign policy, as laid out in the Washington playbook.

James Traub is more moderate but basically agrees. "Hillary Clinton's political agenda does not fundamentally differ from Obama's but the way she views international relations resembles that of Kissinger," he writes - that is to say she sees the world through the lens of political "realism".

For Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, a politics professor at the University of Northwestern near Chicago, Hillary Clinton in the White House might mean new American wars in the Middle East. She thinks that Clinton was never able to "acknowledge the limits of the capacity of the United States to transform the world according to their interests and image". She didn't learn the lessons from her positions on Iraq (as a Democrat Senator she voted in favour of the war declared by George W Bush in 2003) or on Libya.

Her policy in Libya - for which she worked to convince the reluctant administration to start the Benghazi operation -with deadly results - shows how subservient she is to the Washington playbook. Hurd reminds us of the words of warning from Vice President Joe Biden - hostile to US participation in toppling Gaddafi - concerning "not the day after but the decade after" the beginning of a war.

A narrow view of US interests

A quick review of Clinton's attitude during her years as secretary of state (2009-2013) reveals a woman overcome with a narrow vision of American interest, someone who "believes in the exemplary value of a threat more than its actual power", Traub writes. That's why she vehemently criticised President Obama when he failed to follow through on his threat to bomb Syria in August 2013 after Damascus started using chemical weapons, thus crossing the red line his administration had drawn.

According to sources close to her, Clinton reacted violently: "If you say you're going to strike, you don't have a choice: you must do it." For Obama, airstrikes would have achieved nothing except saving face, and would probably have worsened the Syrian tragedy - if such a thing were even possible.

It wasn't the first time that Obama and his secretary of state disagreed. Their first dispute came in 2009 over Afghanistan. American generals on the ground demanded 40,000 extra soldiers, which Obama was reluctant to deliver while Clinton enthusiastically supported the generals' anti-insurgency plan.

|

Her attitude towards Tehran when negotiating the end of its nuclear weapons programme was characterised by marked scepticism and a flair for creating obstacles |  |

In her memoirs, she explains how the Taliban would never agree to negotiate as long as they remained in a position of force. Her plan was to defeat them or weaken them sufficiently to be able to plan ahead. As always, here was the Washington playbook in action once again.

"In retrospect, the generals wildly overestimated America's capacity to make Afghanistan self-sustaining, either militarily or politically. Obama's instincts were right, as they had been in Iraq. Clinton was wrong - as she had been in Iraq," writes Traub.

Her attitude towards Tehran when negotiating the end of its nuclear weapons programme was characterised by marked scepticism and a flair for creating obstacles on the way to the agreement. In her memoirs, she remains supportive of the nuclear deal but shifts focus onto the key role played by the many sanctions put in place to get Tehran to concede.

For Obama, sanctions were always less important than diplomacy and concessions in reaching a final agreement.

Obama, continues Traub, "was willing to help Iran save face, because he understood the need for that. He understands that they also have politics and a history, and therefore he's sceptical that they'll just give in because we talk tough".

Once again, while Obama was shaking off the Washington playbook, Clinton continued to follow its rules.

Sylvain Cypel, a former correspondent for Le Monde, is the author of 'Walled: Israeli Society at an Impasse.'

This is an edited translation of an article originally published by our partners at Orient XXI.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.