Egypt's pharaoh engineers his future

Tahrir's occupation became the symbol of 25 January - of democracy and egalitarianism in the face of Egypt's ruling kleptocracy - so the counter-revolutionaries co-opted and subverted this symbol.

They turned the iconic square into a space for all those forces who wanted to dismantle democracy and reverse all the concrete gains of January 25.

From the day of Sisi's seizure of power, he couldn't simply announce that things were going to get worse than they were under Mubarak to the Egyptian nation, no matter how many Egyptians believed in the absurdly murderous propaganda against the Muslim Brotherhood and the Morsi government.

Vague talk about 'reforms' and 'human rights' and other tidbits of the language of 25 January thus coincided with counter-revolutionary polices carried out to make another 25 January impossible.

In this sense, instead of talking about 3 July, 2013 as 'the coup', we should consider the current political dynamic in Egypt to be a continuous coup.

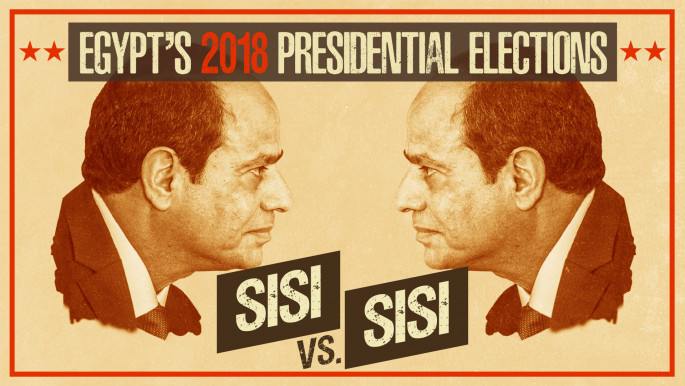

The 'promises' of his seizure of power were only there to be broken. Those who resisted his presidency were subject to murder, arrested, imprisoned or torture, while the 'elections', whether presidential or for the fake parliament, are absurd ceremonies wherein the only people allowed to run are essentially Sisi's own supporters.

Dissenters, even within the milieu of Egypt's powerful elites, are subject to violence.

|

A petition emerged calling for Article 140 to be amended to allow Sisi to remain as president beyond his term |  |

Now perhaps the last pillar of what might be called Sisi's 'revolutionary pretensions' (his pretensions towards being something better than Mubarak), namely the term limits on his presidency, are being prepped to be demolished by his regime.

Almost every Egyptian critic of Sisi saw this moment on the horizon. The presidential limits were set for two terms of four years in Article 140 of the constitution drafted under his rule in 2014, with his presidency set to expire in 2022.

The same constitution which was sold to the Egyptian public as representing a 'New Egypt' of 'Peace, Prosperity and Growth' and which had provisions against torture and human rights abuses - all of this drafted by a regime that is one of the most prolific and efficient torturers and human rights abuser on earth.

There is a time honoured tradition among Egyptian tyrants of justifying tyranny and the forsaking of responsibility by manufacturing faux popular outpourings of support.

Twitter Post

|

Nasser was good at this, such as the moment after the humiliation of the Six-Day War in 1967 when the allegedly broken president resigned, only for hundreds of thousands of Egyptians to come out to demand that he remained as the leader. Of course, almost all of those in the streets were either members of Nasser's Socialist Union or stooges paid by the regime to protest in Nasser's favour.

Sisi isn't so good at it. Hence the constant use of violence.

His presidency, a responsibility that Sisi apparently didn't want, was initiated first by a bunch of groups with names like Masr Balady (Egypt My Country) and Kammel Gemilak (Finish Your Favour), who claimed to have collected 26 million signatures of 'normal Egyptians' to demand that Sisi run for president.

While there's no doubt Sisi at that point had genuine popularity, it was a charade planned from the very beginning by Sisi and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF).

It should have been no surprise then when in August last year, a petition emerged calling for Article 140 to be amended to allow Sisi to remain as president beyond his term limits. Now it seems like later in the year there will be a definitive endeavour by Sisi to erase Article 140.

According to the Egyptian media outlet Mada Masr, sources speaking on condition of anonymity from Egypt's General Intelligence Service (GIS), parliament and the presidential office, have confirmed that these amendments will be rolled out by June of this year and will, among other disturbing things, extend his presidency for an as yet unknown period of time.

It seems that the GIS and, in particular, Sisi's son Mahmoud, who is a senior officer with the GIS, is the main force pushing the amendments around different Egyptian state institutions.

In addition to this, Sisi loyalists in parliament, headed up by Hizb el-Wafd MP and Sisi advisor Bahaa Eddin Abu Shaqqa, have been quietly pressuring the same committee who drafted the constitution to get rid of Article 140.

Many people might wonder why, if Sisi is a tyrant with absolute control, he doesn't just declare himself dictator for life. But tyrannies rarely function like that.

|

'Elections' are absurd ceremonies wherein the only people allowed to run are essentially Sisi's own supporters |  |

Even within a state such as Egypt's that verges on the totalitarian, there are internal logics that govern the tyrannical system. Certain liberal critics of Sisi might imagine that his will to get rid of Article of 140 is some kind of subversion of emerging democracy, but it's more a case of a power play within the fairly diverse ruling forces of the state.

In other words, should Sisi fail in abolishing his term limits, it's highly unlikely a true reformist would replace him, but they also can't take the chance of even a superficial reformist having state power.

This is precisely why Sisi clamped down on even other authoritarian and elite candidates running against him in the staged election of 2018. Within different cliques of Egypt's ruling elite, there exists a spectrum of different opinion, and some - including the likes of Ahmed Shafik - while hardly progressive, understand that Egypt cannot continue down the disastrous path that Sisi is leading it.

|

|

These personalities cannot be controlled and thus might rock what Sisi and his backers consider to be a fairly steady boat.

Egypt's elites know that, to a certain extent, their tyrannical methods are simply securing only their own interests, while much of the country remains ungovernable by those methods.

What happens if Sisi were to disappear after the end of his term and someone came in who actually wanted to address even just some of the huge problems - problems entirely caused by the ruling kleptocracy - that face Egypt?

Getting rid of Article 140 is their insurance policy. But it's not the only one.

According to the same report, even if he fails to amend article 140, there is another plan to create a 'High Council for the Protection of the Constitution', which would effectively annul the above scenario of any kind of reformist being able to function as Egypt's president in the wake of Sisi.

The council would have unprecedented powers to 'safeguard national security', which in Egypt is newspeak for 'safeguard the interests of the ruling elites'.

The head of this unelected council for life would be Abdel Fattah el-Sisi himself.

Outside of Egypt, the regime is seeking to capitalise on the rise of global authoritarianism and anti-immigrant sentiment in the West, with Sisi anxious to get it done while his staunch ally Trump remains in office.

|

We should consider the current political dynamic in Egypt to be a continuous coup |  |

The EU, mired in obsessive and industrial xenophobia against refugees, will provide no obstacles to anything Sisi does, as it continues to provide unconditional support for his regime in the face of the so-called 'refugee crisis'.

The regime is beyond confident that Sisi will get his own way.

One way or another, for at the very least the next decade, Egypt's Pharaoh is going nowhere.

Sam Hamad is an independent Scottish-Egyptian activist and writer.

Join the conversation @The_NewArab

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.