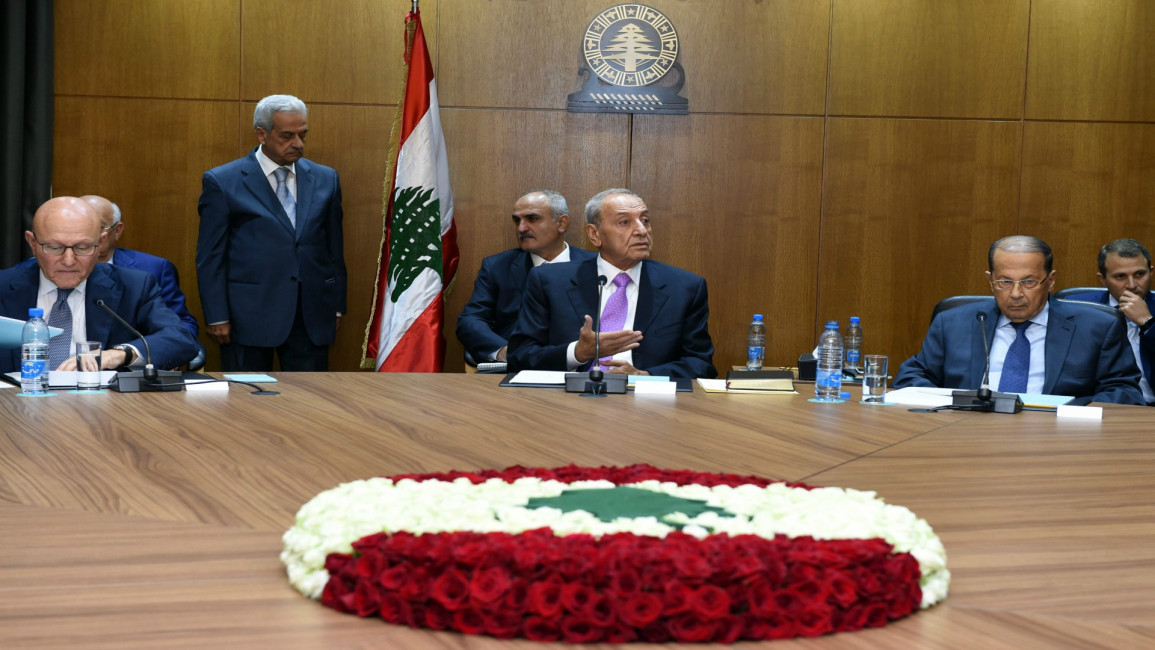

Negative politics and the dysfunctional state of Lebanon

The government in Lebanon continues to flounder amid several crises that have provoked widespread dissent.

There is the failure to elect a president for the past two years, a parliament that does not convene, fears of an economic collapse and increasing taxes, and security concerns over fresh clashes near Arsal between the Islamic State group and the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate.

But whereas the political vacuum resulting from the absence of a president could easily be attributed to legitimate political disagreement, other matters, such as the refuse crisis, seem to be the product only of glaring incompetence.

|

Such a failure of democracy in Lebanon has among its sources the pervasive sectarianism that afflicts the country |  |

As state institutions decay, it seems flabbergasting that members of the legislative and executive bodies continue to elude accountability for their failures.

Xenophobic democracy

It is beyond doubt that such a failure of democracy in Lebanon has among its sources the pervasive sectarianism that afflicts the country. But it is essential to characterise what allows this sectarianism to persist in order to identify potential points of intervention.

Since the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanese territory in 2005, political confessionalist groups have largely been focused on attacking each other under the pretext of protecting its rights as a sect. This has come in a number of forms, most prominently that of depicting other groups as having blind allegiance to foreign regional and international powers, thus questioning the autonomy of their decisions.

Incidentally, such accusations are often well-founded, with political groups embracing "like-minded" overseas powers, such as Hizballah's relationship with Iran or the Future Movement's connections with Saudi Arabia.

However, these attempts at presenting rivals as completely subservient to foreign agendas shape a significant proportion of political campaigns - often their entirety. Through exploiting ready-to-be-deployed xenophobic tendencies, political parties often vie to reserve for themselves the strictly negative role of ensuring survival.

This relieves them from any duty towards the public they represent, and thus renders democracy obsolete, as the process inevitably leads to the reproduction of the same legislative body, year on year.

|

The past decade has seen almost exclusively negative politics in Lebanon, as parties take shelter in communal and sectarian fears |  |

Negativity and accountability

Framing politics in terms of regional allegiances alleviates parties' responsible for their own domestic failures when it comes to state building. What is deemed significant is carrying the obsessions and fears of the group's sect as opposed to putting forward a positive developmental plan, or showing foresight or addressing long-term problems and suggesting appropriate solutions that rectify the everyday concerns of citizens.

The past decade has seen almost exclusively negative politics in Lebanon, as parties take shelter in communal and sectarian fears.

The consequences of this are deeply divisive. Demonising "the other" allows the preservation of the sect to become its primary concern, with sect leaders thriving on exacerbating fears to isolate the community and monopolise its political representation.

| Comment: The importance of being earnest about sectarianism |

The presidential crisis - which has always been framed as "protecting the rights of Christians", rather than a national political priority - is a clear example of exploiting the public's fears, under a persisting deadlock, to entrench positions and bolster support from within the sect.

The pre-2005 period also suffered from such problems. But throughout the Syrian presence in Lebanon, the dynamic under which Lebanese politics operated involved different considerations. The politics of exclusion that operated back then allowed for a relatively functional state, though beset with corruption. Today, however, we find the persistence of corruption in the absence of any functionality.

If this characterisation is accurate, then the question becomes that of reconfiguring the visceral concerns of the public in order to bring to the forefront the demands of everyday life and make room for political accountability.

The significance of the Arab revolts is that they began a shift away from communal allegiances towards the more crucial national questions of development and economic concerns.

Yet such movements require as a condition of viability the existence of a minimal degree of unity within the social body. It comes as no surprise, then, that a more homogenous society, such as Tunisia, was more successful than protests in Lebanon - which have been contained with relative ease, up until this point at least.

It would, however, be naively optimistic to hope for the imminent development of any form of significant national solidarity which could initiate at least the appearance of positive politics in Lebanon.

Karim Barakat is an instructor of philosophy in the American University of Beirut.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.