What we're talking about when we talk about nukes

Nuclear annihilation; the apogee of contemporary warfare, casts by far the largest shadow. Awareness of it and its dangers ebb and flow with time and place, but lately a kind of arrogant ignorance of the nuclear threat has found a home in leaders of the world.

Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, in particular, seem keen on nuclear weapons as political stunts to shore up their macho-man cred. In December 2016, both Trump and Putin made overtures to the idea of expanding their nuclear arsenals, in direct violation of the aims of the UN's Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which both are signatories.

When the UN convened a discussion to draft a possible blanket ban of nuclear weapons in March of this year, Russia, North Korea, and the United States refused to even attend the drafting session.

There is no pretty way to put the danger these idiotic postures portend, nor should there be. Nuclear weapons represent the route to the extinction of human civilisation and perhaps the species.

Anything less than the disassembly of all nuclear weapons and the international shaming of any attempts to make new ones puts countless innocent lives at risk. Any position that isn't a move toward disarmament, regardless of the short-term aims, is a position against existence itself.

|

Anything less than the disassembly of all nuclear weapons puts countless innocent lives at risk |  |

These countries weren't always led by such self-aggrandising dullards. Thirty years ago the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the result of seven years of tooth-and-nail negotiations during the third-hottest time of the Cold War, was signed by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.

The treaty, between the United States and the Soviet Union, successfully eliminated an entire category of shorter-range nuclear weapons, leaving only the long-range, "strategic" weapons in the countries' arsenals.

This sort of good-faith attempt to slowly destroy the present nuclear stockpile is key. If an international actor isn't honestly attempting to reduce their nuclear arms themselves, then what right do they have to dictate to other, non-nuclear states about their nuclear weapons development? It reeks of a lust for supremacy.

|

|

| Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and US President Ronald Reagan sign a treaty eliminating US and Soviet intermediate-range and shorter-range nuke missiles [AFP] |

This is the pickle both Trump and Putin find themselves in with Iran. Why should Iran take seriously the moralistic scoldings of an international community that, if Trump and Putin are to be believed, wants to build more nuclear weapons?

Reagan and Gorbachev in public denounced nuclear arms and negotiated in good faith to have them reduced. Obama, with Secretaries of State Clinton and Kerry, worked to continue forging compromises that would minimise the risk of nuclear escalation, like the New START Treaty and the Iran nuclear deal.

Trump and Putin, leaders of the two countries with perhaps the most influence over Iran's actions, have shifted these policies to one of, "Do as I say, not as I do". Their hypocrisy is plain. They will convince no-one to give up the pursuit of nuclear arms unless they have a sincere desire to follow suit.

|

This sort of good-faith attempt to slowly destroy the present nuclear stockpile is key |  |

Maybe this new ignorance is simply a matter of the passage of time. Neither Trump nor Putin was born before the end of World War Two. To understand what is at stake in nuclear disarmament, they and we must review history.

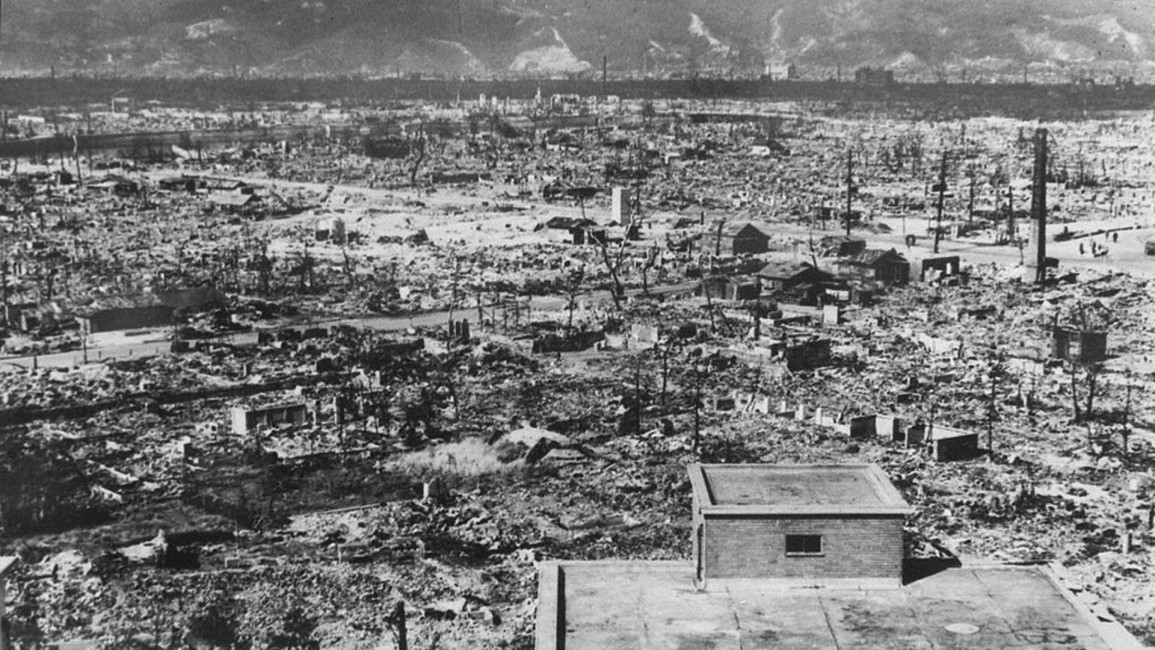

Seventy-two years ago, on 9 August 1945, the second and so far last atomic bomb to be used in combat was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. It drifted from its bomber on a parachute and exploded just above a tennis court.

Everything within a mile radius - factories, homes, businesses, churches, people - was instantly engulfed in a wall of fire nearly as hot as the surface of our sun, and anything left standing was knocked down by winds travelling roughly at the speed of sound.

Between 39,000 and 80,000 people died then and there. Of that, only 150 were Japanese soldiers. The remainder were civilians, undocumented forced labourers, and prisoners of war. The toll from radiation poisoning and other injuries is estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

This was one weapon, a low-powered one by today's standards, whose effects were luckily contained by the hills of Nagasaki. It still ended more lives than we can easily imagine. It still caused unquantifiable suffering for decades after due to radiation poisoning, the grief of surviving family, and psychic trauma. It ended a war, though at what cost?

This is what we're talking about when we talk about nukes. If Trump or Putin care to not repeat the horrors of the past, they should heed the lessons of the dead in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the work of Reagan and Gorbachev, and the Iran nuclear deal negotiations.

The path forward for the species demands disarmament, not by some, but by all.

Nicholas Morley is a researcher and graduate of Brown University. He lives in Burlington, VT.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.