Iran Protests: Women subverting the hyper-masculine order are heroes

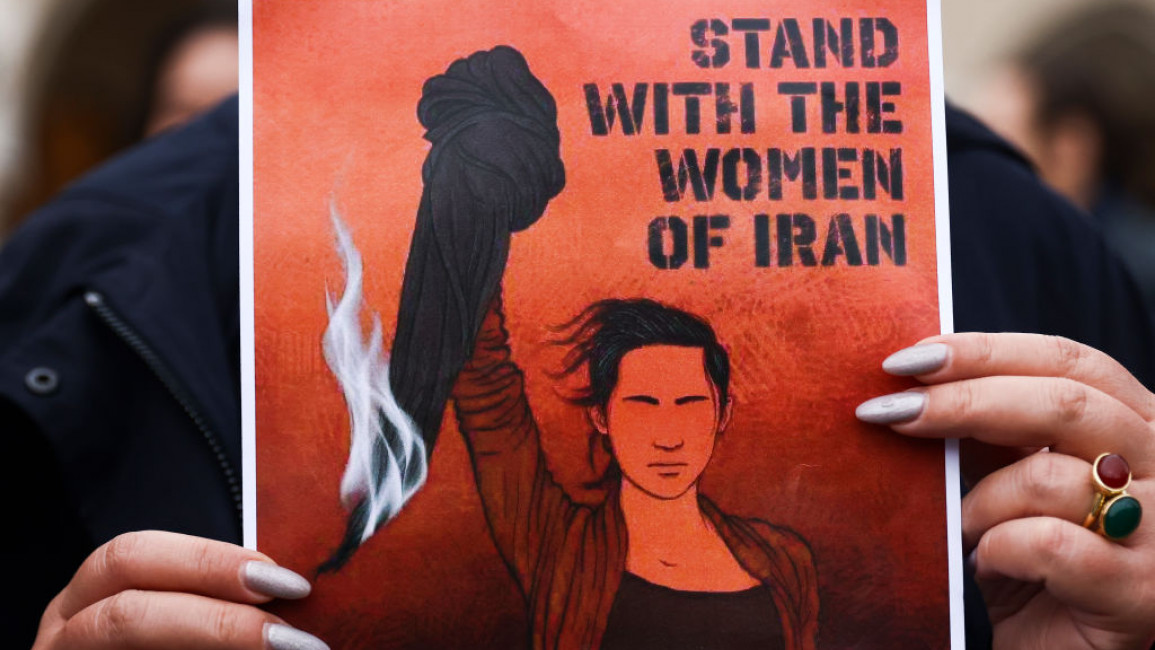

Written on the tombstone of Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Iranian whose death sparked nationwide protests against the mandatory hijab and the rule of the Islamic Republic, are the prescient words “You will not die, your name will be a symbol.” Mahsa’s face now appears on murals, street art, posters, and a constantly expanding repertoire of digital creations.

In less than a month since her death, the Persian hashtag of her name has been used at least 274 million times. Her name and legacy, alongside other women who risked their lives to confront the gender-apartheid of the Islamic Republic, like Nika Shakarami, Sarina Esmailzadeh, and Hadis Najafi, represent the heroes of Iran’s future. They are everyday female citizens and an affront to a governing ideology defined by a pantheon of male heroes and dominated by masculine myth-making.

''The regime has long nurtured a governing ideology that seeks to embody the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet, who died on the battlefield in 680 while struggling for justice against a superior enemy. He is the figure to which the Islamic Republic has tethered its worldview as a country that must confront superior enemies in an unforgiving and belligerent international system, and the model for defenders of the nation, who if successful, will be revered as martyrs.''

Heroes are figures through whom the complex contexts of reality gain a face; their names become symbols mobilising communities and galvanising societies. They are borne from single moments that give expression to broadly-held experiences, and can serve to reject an entire system and its sinister history, like the sisters Dina and Dunya Rad, who ate breakfast without hijab in a restaurant, the women twirling headscarves in the street, those posing with cut hair, or the schoolgirls who defiantly shake their hijabs in front of male administrators.

These are the many heroes who perform rebellious acts in public – risking their freedom in hope of change – and behind whom the protest movement rallies. They represent a new cadre of heroes to the Iranian nation and serve as an inspiration to others at home, and elsewhere. Their actions are replicated and circulated online forming a constantly multiplying gallery of feminist images and icons in defiance of the state.

They are not only challenging one of the Islamic Republic’s most identifiable symbols, the hijab, but also forcibly removing its ownership over who can be a hero and martyr for the nation. As a collective, their actions and legacies subvert the hyper-masculine gender order in Iran, built on the tales of men as the agents of history.

The Islamic Republic, as a Shia theocracy, is grounded in the social power of the heroic, and the veneration of individual sacrifice on behalf of the community.

The regime has long nurtured a governing ideology that seeks to embody the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet, who died on the battlefield in 680 while struggling for justice against a superior enemy. He is the figure to which the Islamic Republic has tethered its worldview as a country that must confront superior enemies in an unforgiving and belligerent international system, and the model for defenders of the nation, who if successful, will be revered as martyrs.

Populating murals and posters across Iran’s urban landscapes is the Islamic Republic’s pantheon of these fallen heroes. They comprise both unassuming faces from the Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War as well as more recognisable ones, like the assassinated Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander Qassem Suleimani and nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. They are unmistakably male.

Despite the participation and sacrifice of women during the revolution, Iran-Iraq War, and beyond, defending and dying for the nation is recognised in the Islamic Republic as an almost exclusively male affair. Women are assigned to witness the heroic acts of their male brethren on the battlefield and mourn their loss.

Like Husayn’s sister Zaynab, who witnessed her own brother’s sacrifice but did not participate in battle, women in Iran are rarely recognised as active participants in the actual fight for justice and as defenders of the nation.

Undeterred by this secondary status, women have persevered and excelled in literature and the arts, education, and medicine. They have continually defied social norms and employment discrimination, which they are faced with despite attaining degrees at a higher rate than men.

The endgame of these latest protests may be uncertain, but it is clear that the prescribed male-dominated order of the Islamic Republic, where many women feature as background actors in a play not of their choosing, is as tenuous as restrictions on the hijab. The new heroes of Iran’s future are not those iconic male martyrs revered for confronting the injustice of a superior enemy abroad, but the young women confronting it at home, laying the inspirational groundwork for a new generation and societal order.

Kevin L. Schwartz is a Research Fellow and Deputy Director of Research at the Oriental Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic.

Olmo Gölz is a Senior lecturer in Islamic and Iranian Studies in the Department for Oriental Studies, University of Freiburg, Germany.

Follow Olmo on Twitter: @olmo_goelz

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.