World Refugee Day: Children failed by an inadequate system

This year, World Refugee Day has arrived in conjunction with what could be called the precipice of the refugee crisis. Migration of those fleeing conflict has reached unprecedented levels: Since January 2015, 1.2 million people have made the perilous journey across the Mediterranean sea to reach Europe; in 2016 so far, 35% of arrivals by sea have been children and 27% of all asylum applications (95,080) have been for children.

Amid the frenzied campaigning around Brexit, the "Remain" campaign has engaged in scaremongering and issued warnings of "swarms of migrants" entering Britain; but this doesn't change the reality that the majority of these migrants have their own harrowing stories that have left them with no other choice.

It is therefore, more important than ever to stand together with refugees this year.

The most vulnerable in this situation are the thousands of children who have had to make the journey on their own and who are open to exploitation and abuse at the hands of traffickers and smugglers.

As well as the physical threats and fear that come with fleeing home, the psychological impact on minors undertaking a journey fraught with danger and facing systemic rigmarole, is something that has been overlooked, as they are politically negotiated in terms of "numbers", "resources" and "capacity considerations".

Badly formulated arguments such as avoiding the "pull effect", further compound the precarious situation that unaccompanied minors wanting to enter Britain are faced with. Engaging in political bargaining, the UK is falling short of European regulations and the international law it is bound to comply with.

UNICEF recently underlined some of these shortcomings in two recent reports, Neither Safe Nor Sound and Danger Every Step of the Way, highlighting the situation of unaccompanied minors and children arriving in Europe.

|

An additional problem is the very narrow definition the UK government sees in the term "family" - restricting it to the nuclear family only |  |

The reports illustrate that children are falling through the cracks of an already ineffective asylum system. Many end up in detention, police custody or child protection centres that do not have the necessary protection safeguards in place. Asylum procedures can take up to two years and they often experience discrimination, exploitation and abuse even once they reach their destination.

It is however, the France-UK juncture that is causing some significant problems, impacting the entry of children into the UK.

Children in the camps of Northern France, such as Calais and Dunkirk, have no intention of staying in France and are determined to reach England. There is therefore, limited protection that can be sought in France itself as the system does not have adequate mechanisms in place, even when recognising victims of trafficking.

The UK has previously been unwilling however, to receive unaccompanied minors from France, who perceive Britain as a safe country. While many unaccompanied minors seeking asylum in the UK hope to join family members already here - a right under the family reunification policy in an EU directive, otherwise known as the "Dublin III" regulation - this is not always possible.

This is due to the very narrow definition the UK government sees in the term "family" - restricting it to the nuclear family only. It does not include an uncle, aunt or other extended family member - thereby denying the cultural definitions of what that child may consider family to be, and further denying what is in the best interests of the child.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Placing the best interests of the child first, is at the heart of the International Covenant on the Rights of the Child, an international treaty that was ratified by the UK in the form of the Children Act 1989.

In May, David Cameron expressed a change of heart and conceded that Britain would take "more" unaccompanied children from Europe - and not just Syrian refugee camps - but this is still not enough.

The Dublin III regulation needs to be reformed to take into account the wider definition of "family", and the time it takes to process asylum claims must be dramatically reduced. Cameron stated that exact "numbers" of how many children Britain will take is unknown and dependent on local authority "capacity constraints".

Typically, asylum applications are turned around in three months and this is the expected standard. For a child to be awaiting decision for two years is disproportionate and an infringement on their right to family life.

If David Cameron and his Conservative government are to take the plight of unaccompanied children more seriously, they will need to dedicate more resources to a currently ineffective asylum system. The capacities of the Home Office and local authorities will need to be increased.

|

This World Refugee Day political leaders should reflect on the thousands of people they have let down; a third of them children |  |

Unfolding over the last 18 months, Europe's handling of the refugee crisis has been disgraceful, and this World Refugee Day political leaders should reflect on the thousands of people they have let down; a third of them children.

Deaths and disappearances could have been avoided if lives and the right to life had been considered paramount. Adequate legal and safe migratory routes would negate the need for irregular methods, and children would no longer need to approach smugglers or fall into the hands of traffickers.

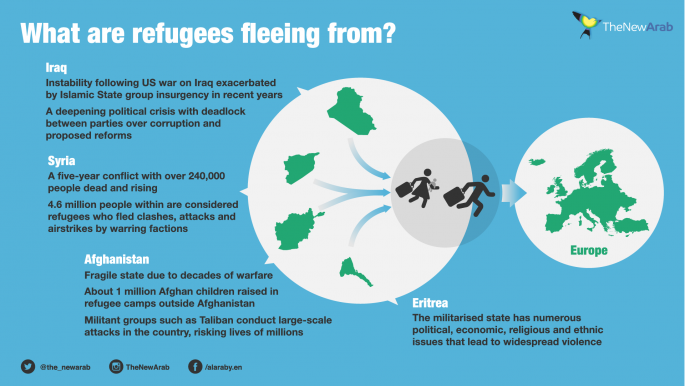

Existing analysis already tells us that the majority of migrants are travelling from conflict-affected states and will likely be eligible for refugee status. Policy efforts, therefore, should concentrate on how to clear people for entry before they get on boats. This could be achieved by opening up desks at embassies in third countries, and children, as the most vulnerable, should be put at the front of the queue.

At this juncture, the UK should at the very least, muster up the political will to act, and to play its part in alleviating the suffering of the many children who are still alone. In order to do so, a greater focus on family reunification is required and the rights of the child must be respected.

Sophia Akram is a researcher and communications professional with a special interest in human rights particularly across the Middle East. Follow her on Twitter: @mssophiaakram

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.