Bigger, not better: Assessing Trump's latest bombing of Syria

The United States' second bombing of Syrian regime targets with cruise missiles is certainly distinguishable in some distinct ways from its first bombing this time last year. While in its immediate aftermath, it's hard to determine exactly what its ultimate outcome will be, if previous US responses to the use of gas by Syria's dictator Bashar al-Assad are anything to go by then this latest attack is highly unlikely to have any real impact on the Syrian battlefield.

The strike

The strike was by far the biggest against the Syrian regime to date and was a response to the regime's alleged killing of approximately 70 people in the town of Douma in East Ghouta near Damascus on April 7 using gas – the choking agent chlorine and, according to the US, possibly the far more lethal sarin nerve gas.

It was also the first time the militaries of France and the United Kingdom worked in unison with the United States against Damascus. All fired air and ship-launched cruise missiles to strike the three targets: the Barzah Research Center in Damascus and the Him Shinshar chemical weapons storage facility in Homs Province, along with a second chemical storage site in the same area.

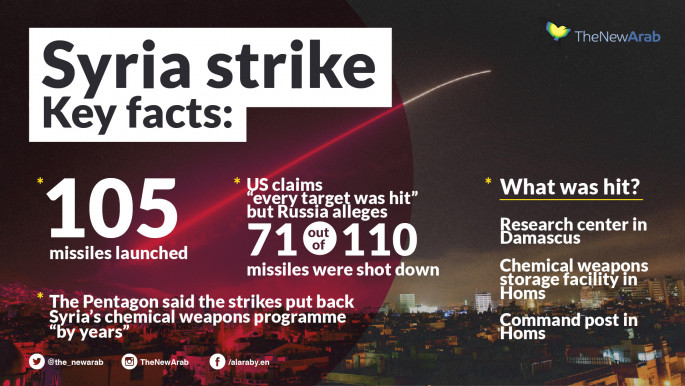

A total of 76 missiles descended on Barzah, 22 on Him Shinshar and seven on the nearby site almost simultaneously at 4am Syrian time. The US claims that all missiles reached their targets and “significantly crippled” the remnants of Syria's chemical stockpiles and production capabilities, setting it back “by years”.

While the US used the same ship-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles that previously targeted Syria's Shayrat airbase in April 2017 it also fired air-launched AGM-158 JASSM-ER missiles for the first time in combat. Launched from B-1 Lancer heavy bombers flying from the Gulf, escorted by jet fighters and electronic warfare planes, these missiles have a range of 1,000 kilometres and pack the same 1,000-pound payload as the iconic Tomahawk.

|

For their part, the British and French launched a smaller, but formidable array of missiles at the same targets. Both powers fired Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles, different variants of the same missile (which are called 'SCALP EG' in French service), at the targets – the British using their Tornado GR4 jets and the French using their Dassault Rafale and Mirage 2000s. Those missiles have a rough operational range of 560 kilometres and carry a 990-pound payload. France also fired three ship-launched Missile de Croisière Naval (MdCN) cruise missiles, the naval version of the aforementioned Storm Shadow missile.

This total strike package of 105 of these sophisticated missiles against a mere three targets is a stupendous amount of firepower and, with most missiles costing at least $1 million per piece, a true embarrassment of riches.

The outcome

US President Donald Trump immediately declared the attack a resounding success, dubiously claiming in a tweet that it: “Could not have had a better result. Mission Accomplished!”

Leaders and officials from all three countries which executed the strike sought to emphasise and stress that it was a limited, one-off incident and not aimed at toppling Assad.

Despite heated rhetoric from both Trump and Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, it's clear that this attack will not result in any clashes between the Western and Russian militaries in Syria. The New York Times reported that there was “a palpable sense of relief” in Moscow in the immediate aftermath of the strike as a result. The US ambassador to Russia published a statement on Facebook in which he clarified that: “Before we took action, the US communicated with the RF [Russian Federation] to reduce the danger of any Russian or civilian casualties.”

A pro-Syrian regime official told Reuters that Damascus had successfully absorbed the strike thanks to a Russian warning. “We had an early warning of the strike from the Russians… and all military bases were evacuated a few days ago,” the official claimed. Washington may well have provided Moscow with information about the targets it planned to destroy beforehand, through the communications mechanism both powers maintain in Syria to avoid any clashes or misunderstandings between their two militaries there.

On the eve of the attack, Sheikh Naim Qassem, the deputy leader of the Iran-backed, Syrian-allied Hizballah militia in Lebanon, ruled out “the situation developing into a direct American-Russian clash or a wide state of war”. This, he added, was “unless Trump and [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu completely lose their minds”. Hizballah's leader, Hassan Nasrallah, however, believes there is a prospect of an Iran-Israel war after Tel Aviv carried out an airstrike against the T-4 airbase in the eastern countryside of Homs province on April 9, killing an estimated seven of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) paramilitary troops.

While Damascus and Moscow claimed that several of the coalition's missiles were shot down, this is, in reality, highly unlikely. US Lieutenant General Kenneth McKenzie, a director of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that the Syrians did launch 40 surface-to-air missiles at the incoming cruise missiles, but they were launched using a “ballistic trajectory” and “without guidance”, meaning they had very little chance of hitting their fast-moving targets. Even if all of the Syrian missiles each took down an incoming cruise missile, more than half of the enormous strike package would still have made it to their targets and likely destroyed them anyway.

McKenzie went on to point out that the unguided Syrian missiles “had to come down somewhere” and subsequently ran the risk of harming Syrian civilians. The Pentagon claims that the sites targeted “were chosen to minimise civilian loss of life and possible release of chemical agents”.

|

The attack did nothing to influence the outcome of the East Ghouta battle, where the chemicals were used. Shortly after gas was used, Assad's opponents there were evacuated to Syria's northwestern Idlib Province - which is still held by the Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) militant group - upon surrendering Douma. Mere hours after the April 14 attack the Syrian Army claimed victory in East Ghouta which, if true, constitutes the biggest defeat for anti-Assad forces since the regime's prior victory in East Aleppo in December 2016. It remains unclear if the use of chemical weapons had a decisive affect in speeding up the regime's takeover of East Ghouta. If they did then that may, at least partially, explain why Assad may have decided to use them in full knowledge that there would be some, albeit limited and surgical, Western retribution against his regime.

Informative precedents

There are two precedents in Syria for this latest US-led action. They are the April 2017 US rocketing of Shayrat airbase, following the Khan Sheikhoun gas attack that same month, and the US-led threat to bomb Syria in August 2013, following that month's lethal gas attack in East Ghouta, which was not executed.

The Shayrat attack was a more simple case. The US acted alone in a similar one-off strike consisting of 59 ship-launched Tomahawk missiles concentrated on a single target. If the regime is conclusively proven to be behind the Douma attack, then it's clear that that action failed to deter Damascus long-term. While this month's strike was backed by the British and the French and encompassed more than a single target it was essentially a larger repeat of the Shayrat strike and may well have as little chance of deterring Damascus against using chemicals in the months and years to come.

The 2013 precedent, when the US threatened to respond to Syria's deadly use of sarin gas in East Ghouta but instead settled for a deal, is much more informative. In the five years since there have been many articles speculating how differently the Syrian conflict might have unfolded had the Western powers attacked then, before Russia established its overt military presence in the country, instead of supporting UN Security Council Resolution 2118, which obliged Syria to surrender its chemical stockpile to avoid coming under attack. While Damascus has indeed used chemicals on various occasions, since none were as lethal as the attack that August, in which several hundred perished from exposure to sarin. Furthermore, what likely amounted to the vast bulk of Syria's known stockpile was verifiably surrendered, successfully removed from the country and rendered inert as a direct result of 2118. Had the US instead led an attack back then they would have had to hit far more sites in order to destroy a much larger arsenal.

While Trump retrospectively criticised the Obama administration recently for failing to confront Assad in enforcement of his “red-line” on chemical weapons, neither Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu - who nobody would argue is dovish regarding Syria - expressed his support for that move at the time. He even went so far as to call it “the one ray of light in a very dark region”. While he did express, in retrospect prescient, concern that “they may not have declared all of their capacity,” he nevertheless went on to add that, “But what has been removed has been removed. We're talking about 90 percent. We appreciate the effort that has been made and the results that have been achieved.”

It remains unclear if President Trump's two brief one-day attacks on Syria will ultimately achieve a more significant outcome than that flawed arrangement did in preventing Assad from using poisonous unconventional weapons on the war-weary Syrian people.

Paul Iddon is a freelance journalist based in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, who writes about Middle East affairs.

Follow him on Twitter: @pauliddon