Stop Uighur internment camps or take the Olympics away from China

One woman describes the moment she came to know that she would never be able to carry children of her own, behind the bars of the country's internment camp.

"We had to stick our arms out through a small opening in the door. We soon realised after our injections that we didn't get out periods anymore."

Another Uighur refugee, Mihrigul Tursun, testified in front of a US Congressional Executive Commission on China last November and revealed that detainees in camps were starved, beaten, electrocuted, and strip-searched.

She said: "My hands bled from their beatings, each time I was electrocuted, my whole body would shake violently, and I could feel the pain in my veins. I thought I would rather die than go through this torture and begged them to kill me".

Sadam Abdusalamu and Almas Nazamidin have been separated from their wives and children, unable to return to their families, and Australian Uighur Hayrullah Mai was detained for three weeks in 2017 whilst visiting relatives in Xinjiang.

Akida, an Uighur from Xinjiang, is desperate for the return of her mother Rahile Dawut, who she says has been detained by the Chinese government since 2017.

"She is an amazing mother," Akida says. She and her mother spoke on the phone daily, but on December 12, 2017, she never heard from her mum again. Akida believes it is because she's been taken away to an internment camp where over a million Muslims are kept as the country clamps down on Muslims and their worship.

China's Foreign Ministry has consistently denied such claims, and called Tursun's account a "complete lie told with ulterior moment" and according to Hua Chunying, a spokesperson, Mihirigul was taken into custody by Qiemo County police for 20 days from April 21 to May 20, 2017 on suspicion of inciting ethnic hatred and discrimination, but she was never jailed or put in a "vocational training" centre (the government's term for the internment camps).

China has repeatedly denied the existence of such camps, and denies accusations of human rights abuses, calling it "fake news". It has begrudgingly admitted to the existence "vocational training centres" which it insists doesn't violate human rights despite a growing body of evidence suggesting otherwise.

|

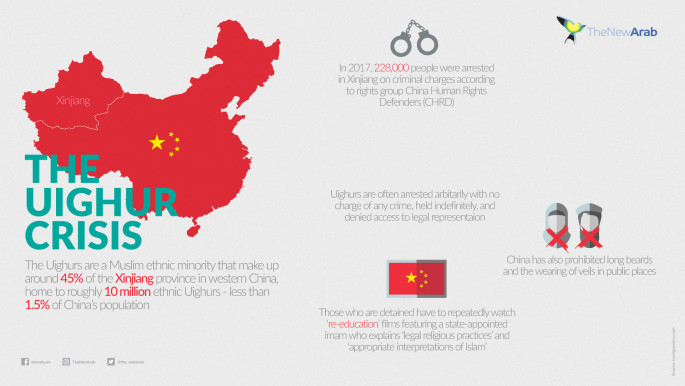

These stories of detention, disappearance and abuse of the Turkic-speaking Muslims in China are by no means exceptional: Countless accounts from Uighur refugees from the past three years detail human rights abuses they were subjected to when they had been stolen – sometimes in their thousands – to camps in the north-western Chinese autonomous state in what is becoming systematic persecution of ethnic and religious minorities in China.

'No Rights. No Games'

No Rights. No Games is a campaign launched by Uighur activists from around the world who have joined to urge China to close its internment camps, where over one million Uighur Muslims are being tortured and "re-educated," before the 2022 Winter Olympics arrive.

The winter games are set to take place in Beijing from February 4 to February 20.

"For China to successfully host," they write in their mission statement, "they must fall in line with the stated principles of the Olympic Charter" which includes respect for ethical principles and the promotion of a peaceful society.

More than 61,000 people have signed the Change.org petition since the writing of this article.

The New Arab reached out to the IOC and asked if it was willing to relocate to a different country if the camps are not closed. In an email statement it said that while human rights are enshrined in its charter, it "has neither the mandate nor the capability to change the laws or the political system of a sovereign country".

It went on to say that it had "considered the views of independent NGOs" and the "issues were raised with the government and local authorities".

The IOC added that it had received "assurances that the principles of the Olympic Charter will be respected in the context of the Games".

This response appears in line with the Olympics' previous abstinence from political issues. In 2018 North Korea, long regarded as an authoritarian state that has committed multiple human rights abuses, hosted the Winter Olympics in Pyongchang.

Read More: Top ten things to look out for in the year ahead

The China Cables

The Chinese government has consistently denied the existence of internment camps. However leaked documents were released in November and showed China's systematic incarceration, torture and brainwashing of predominantly Uighur Muslims.

The leaked documents, described by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) as using "Orwellian doublespeak," shows that the Chinese government controls everything these "students" – how they refer to the inmates – can do in the "vocational training centres," including when they can go to the toilet and when they can see their loved ones.

|

China serves as a warning that an authoritarian regime, underpinned by surveillance technology, exists and may be ready for exportation.

What is particularly nefarious about this government- sanctioned camp process is its integration of an analysis system that uses artificial intelligence to monitor the Muslim citizens of the state, including putting QR codes on doors to determine who is inside the house at all times, and select entire categories of Xinjiang residents for detention based on big data analysis.

"The implications are dramatic," Adrian Zenz, an expert on Xinjiang and China's policies told the ICIJ.

"With these digital information systems, [the Chinese government] believes it can gauge what a person really does, what a person really believes. What are they doing on a regular basis? How are they really behaving? What are they saying when nobody listens?"

The China Cables reveals a system that collects a huge amount of personal and private data, which they use to conduct warrantless searches, install facial recognition cameras to survey the Muslim population and track people's online behaviour to determine what apps they use, flagrantly violating human rights convention again and again.

The centres are designed to force detainees to pledge allegiance to the Chinese Communist party and has a rewards system based on renouncing their faith and discontinuing the use of their mother tongue.

According to one document, a nine-page memo sent out in 2017 by Zhu Hailun, then deputy-secretary of Xinjiang's Communist Party, there were clear instructions that the camps be run as high security prisons where escapes were "never allowed," infractions were to be severely punished, "remedial Mandarin" was to be a teaching priority and "full video surveillance coverage of dormitories and classrooms free of blind spots" were to take precedence.

Xinjiang has called the 403 pages of documents "fabricated" and prompted by "hostile foreign forces" despite multiple experts confirming its authenticity.

Piling on the pressure

International response to the horrific camps is gaining traction. Last month Dolkun Isa, the exiled leader of the Uighurs and the president of the World Uyghur Congress said that the leak proves there was no more room for silence.

"These documents were leaked, there is no longer any excuse for silence. The documents show everything very clearly. The documents bring more international attention, more international pressure to the Chinese government."

|

|

Thousands of Muslims held rally in front of China Embassy, in Jakarta, Indonesia [Getty] |

Isa called on governments to stop free trade with China to pile on the pressure.

"It is not time for business as usual," he told Reuters. "So that's why we expressed to the Swiss government to stop free trade cooperation with China and also it is not the right time that Swiss companies continue their business with China."

Though many countries have expressed outrage on both a national and state level, action against China is not forthcoming yet.

A collection of 23 countries confronted China at the United Nations earlier this month, and British UN Ambassador Karen Pierce delivered a joint statement on Xinjiang at the General Assembly's Third Committee.

They shared concerns brought up by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination regarding the "credible reports of mass detention; efforts to restrict cultural and religious practices; mass surveillance disproportionately targeting ethnic Uighurs; and other human rights violations and abuses".

Amnesty International have repeatedly condemned China's actions in Xinjiang, and there is some movement in US congress to recognise the crisis.

The US House of Representatives approved a bill that would mean the Trump administration must offer a strong response to China.

The Uighur Act of 2019 is a stronger version of a bill that passed in September, much to Beijing's chagrin.

It passed with an overwhelming 407-1.

The bill calls on Trump to impose sanctions for the first time on China's autonomous state and the closure of the camps, despite seeking trade deals with the country.

Labour Emily Thornberry recently asked Secretary of State Dominic Raab in "what recent representations he has made to his Chinese counterpart on the detention of Uighur Muslims in China," to which he responded that the UK has applied diplomatic pressure, calling on China to give the United Nations observers "immediate and unfettered access" to detention camps in Xinjiang.

The EU has also called for sanctions against China.

It remains to be seen if gentle prodding will prove successful in closing the camps, but alongside official channels of condemnation, protests against China have erupted across the world and people have been using social media, such as Tik Tok and Instagram, to raise awareness.

Narjas Zatat is a staff journalist at The New Arab.

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram to stay connected