The Arab-American Papers: The emigrant associations at the forefront of Arab independence

How was the author Mikhail Naimy connected to the secret society which was founded by Arab immigrants in America? How did the Arab diaspora there support the Great Syrian Revolt in 1925 and what was the effect of the Sykes-Picot Agreement on their activities? How did their political organisations develop in America at the start of the 20th century?

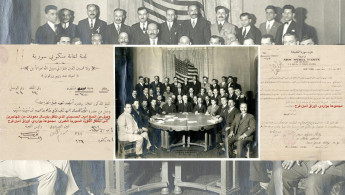

A number of documents that Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, The New Arab’s Arabic-language sister publication was able to obtain provide answers to these questions. Dr Hani Bawardi, Associate Professor of History at the Centre of Arab American Studies in the University of Michigan, was given the archival collection by “Roy” Farah who inherited them from his father Ameen Farah – the founder of the Free Syria Society - who had kept them in the basement of his home in Flint City in Michigan State.

These documents show a little-known side of the history of the early Arab diaspora in America and uncover the strong interaction this community had with the early Arab revolts in their home countries against the British and French Mandate forces.

They also shed light on the industrious Arab-American associations which were established, starting with the secretive Free Syria Society (founded in 1915), followed by the “Syria Relief Committee” – which raised funds to support the Arab fight for independence in the twenties – before more public-facing societies were formed which succeeded in gaining influence in the American Congress and even the White House. However, this political dynamism had disappeared by the end of the fifties and was nowhere to be seen among the second generation of Arab emigrants in America.

Mikhail Naimy’s political work

Lebanese philosopher and author Mikhail Naimy published an article in 1915 in Mira’at al-Gharb (Mirror of the West), one of the mahjari Arab-American newspapers (mahjar is the term for the Ottoman-era Arab immigrants to the Americas and is especially used to describe the literary movement that flourished among this community), which talked about Jewish settlement in Palestine and the theft of Palestinian lands.

It went on to decry the French and English support for the foreign domination of Palestine, calling for Arab and Palestinian public opinion to wake up and fight against these plans. Ameen Farah, the Palestinian émigré in America (lived between 1888-1975) read this article, says Dr Bawardi, and contacted Naimy, asking him to join the Free Syria Society. Naimy, who was a law student at Washington University, responded with a letter of acquaintance on 7 March 1915.

The only time Naimy alluded to his membership of the Free Syria Society was in his autobiography, and even then he did not refer to it clearly, using only symbols to hint at his involvement and not even stating Ameen Farah’s full name.

Relaunching Al-Funoon

Bawardi believes that Naimy agreed to join the Free Syria Society with the aim of befriending Ragheb Metraj, one of Farah’s wealthy friends in Flint City, in order to ask for financial support with which to re-launch Al-Funoon (an Arabic-language literary magazine founded in New York City in 1913) which was regarded as the official magazine of the New York Pen League (an Arabic-language literary society also based in New York).

Naimy succeeded in gathering the required funds and the magazine was re-published in 1916, with Naimy and Metraj co-editing. This is proved by the first and only remaining page of the second letter between them, in which Naimy expresses his interest in publishing literary works and translations of Western literature.

Naimy did not appear to attach much importance to the Free Syria Society in his writings despite his clear calls for Arab independence – especially in the light of the fact that the Free Syria Society represented a significant Arab-American attempt to support Syrian independence and pan-Arab nationalism and as such, documenting its history would surely have been regarded as important, says Bawardi.

Arab-American relief efforts for the Great Syrian Revolt

The third document, entitled The Syria Relief Committee reveals details of fundraising campaigns launched to help the revolutionaries during the Great Syrian Revolt, which broke out against the French occupation on 21 July 1925 and was led by rebel leaders from Jabal al-Arab (the Druze mountains in Southern Syria).

These fighters were joined by others from across Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, who had been brought together under the leadership of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, as many of the region’s tribal factions united in their opposition to the dictatorial, imperialist policies being imposed by the French in order to divide Syria into separate statelets, and which were stirring up sectarian tensions and threatening the Arab culture and character of the country.

Because it was impossible for the emigrants to send financial assistance to the revolutionaries directly, they sought the help of Hajj Amin Al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, to transfer the funds to Sultan Pasha al-Atrash. This confirms that extensive coordination and cooperation was underway between the Syrians, Palestinians, and their compatriots who had emigrated to America.

Founding a new party in the American mahjar

The voluntary work undertaken through the Syria Relief Committee then transformed into a new and more organised channel of resistance as the “New Syria Party”. Founders included Farah and the poet and political activist Abbas Mahmoud Abu Shaqra, who had emigrated to the United States in 1907 and had established the al-Burhan newspaper in 1920, as well as other Arab immigrants who were living in Detroit. Abu Shaqra was elected general secretary of the New Syria Party in 1926.

The party’s goal was to ensure Syria remained independent and unfragmented and to challenge the Sykes-Picot Agreement which aimed to divide the Fertile Crescent region comprised of Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon.

Party branch organisation was meticulous, as is made clear by the document issued from the party headquarters in Highland Park, Detroit. For instance, every branch secretary was required to submit a full statement every three months to the general secretary which included the number of members and the branch funds available.

Branch meetings had to take place at least once a month, and at every meeting, members were urged to donate as much as they could. The money would then be transferred within three days to the general secretary, to be sent from the party headquarters to the central committee in Jerusalem for transferral to assist with the revolutionary efforts.

The sixth document is a publication from the New York branch of the New Syria Party which explains that its activities were not confined to Detroit and that there were a number of other branches in other American states as well as Canada and Mexico.

The party’s goal was to ensure Syria remained independent and unfragmented, and to challenge the Sykes-Picot Agreement which aimed to divide the Fertile Crescent region comprised of Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon

One of the main aims of the party, which brought together Farah, Abu Shaqra, Mahmoud Abu al-Filat and other Arab emigrants, was to oppose the European designs on Greater Syria (or Bilad al-Sham), says Dr Bawardi. It was more organised, widespread and influential than the secret Free Syria Society which had preceded it. There were a number of reasons for this, such as the fact that its members would publish their views and aspirations in English. It was also able to wield a level of political pressure through contact with members of the American Congress. This contact allowed for discussion on the issue to take place at high levels, and Dr Bawardi explains that this kind of contact was possible due to its members’ standing as financially secure settled emigrants who had been united by the Syrian issue.

The pinnacle of the New Syria Party’s achievements was the convening of two conferences, the second of which was in Michigan on 27 January 1927. Members of branches from the different states, Canada and Mexico gathered for the momentous event, and Prince Shakib Arslan and Nasib Saiba'a who represented Greater Syria in the League of Nations attended as guests.

The essence of the Arab-American identity

In 1929, Israeli settlements in Palestine began to rise sharply, with Palestinian land and property being seized for the purpose. On 16 May 1936, Haj Amin al-Husseini announced “Palestine Day” and called for a general strike. A few months later, an uprising broke out – this became known as the “Great Revolt” against the British Mandate over Palestine. The revolutionaries’ demands were independence and an end to the pro-Zionist policy of open-ended Jewish immigration.

The Arab emigrants expressed their solidarity and support with the establishment of a new organisation, the Arab National League (which existed from 1936-1941), the founding document of which we were able to obtain. The League is considered to have been among the largest of the political Arab institutions in the diaspora. It actively sought to educate American society about the culture and history of the Arabs, whilst also supporting Arab integration into American society.

The Arab National League organised four conferences and its fourth conference which took place in Michigan state is considered to have been the birthplace of the American-Arab identity – one of the conference speakers, who went by the name Yusef Yusef, stated: “We Arabs are proud not only of our Arab heritage but also of our existence as Arab Americans”. The content of speeches given at the conference makes it clear that there was a high level of awareness around the need for a strong and well-organised Arab-American community.

The League is considered to have been among the largest of the political Arab institutions in the diaspora. It actively sought to educate American society about the culture and history of the Arabs, whilst also supporting Arab integration into American society

In 1943, shortly before the Second World War, a new political Arab-American institute was established in New York: the Institute of Arab-American Affairs. It was founded by Fuad Shatara alongside others who were supportive of Arab issues, most notably Habib Ibrahim Katibah, and Professor Philip Hitti, who was the first academic specialist of Middle Eastern Studies in the United States.

Other famous patrons of the institute were William Ernest Hocking, Kermit Roosefeld (grandson of the American President Theodore Roosefeld) and the dean of Barnard College, Virginia Gildersleeve. Its director was Dr Khalil Totah.

The institute was the most successful of the Arab institutions in approaching the American policy-making centres, which enabled its members to have their views presented in Congress and even in the White House. However, they were not nearly as powerful and influential as the contemporaneous Jewish institutions which were much more heavily represented in both and were much better funded. By the end of 1950, after the Nakba, harassment increased against members and supporters of the institute, and a boycott was levelled against anyone offering it financial support, which forced its founders to suspend its activities in 1951.

This is an edited translation from our Arabic edition. To read the original click here.