A coup, power and the devastating political consequences of direct military rule: Egypt under El-Sisi

Did the 2011 Egyptian Arab Spring unleash a revolution that nobody, not even the revolutionaries themselves, wanted?

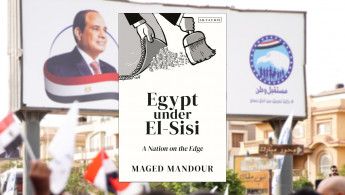

Maged Mandour’s Egypt under El-Sisi: A Nation on the Edge makes the argument that the leadership and rule of Abdel Fattah El-Sisi represents a radical break from Egyptian history and is profoundly different from any Egyptian regime post-1952.

While the presence of the military is not new, “The military establishment proceeded to impose deep structure changes in a manner that can be described as ‘Revolutionary’ indicating that Egypt’s ‘Revolutionary Situation’ resulted in ‘Revolutionary outcomes’.”

These changes were the antithesis of the demands of the pro-revolutionary movement as they represent a deepening authoritarianism, argues Mandour.

To better grasp the revolutionary changes brought in under Sisi, the book turns to Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci and his concept of passive revolution.

Much like in the Italian experience, unlike in the British and French experiences — where a complete social revolution occurred with the popular participation of the masses — Italian elites were unable to impose their control over most of the country. So to unleash social change, the northern elites were forced to ally themselves with southern landowners.

This model limited the involvement of ordinary working people and this concept is useful for thinking through the Egyptian experience.

"The book delves into legal and institutional changes made under Sisi, examines different social policies in which Sisi is both a conservative and a reformer, as well as the increased brazenness in which security forces act in Egypt"

While Mandour thinks the Gramscian concept of the ‘passive revolution’ is an apt one, he does acknowledge there are two major exceptions to it in the case of Sisi.

Firstly, in Italy, the elite was too weak to impose change on society, whereas for Sisi the opposite was true and a stronger state was built under his leadership.

The second one is popular participation does oddly exist in that Sisi can mobilise the public whenever required — he has done so while eliminating all avenues for popular participation in the public sphere.

|

This is the key aspect that characterises Egypt today — Sisi can play both sides of the street and we see this in several different areas.

However, Mandour would caution us against thinking that this means Sisi’s system is stable in the long term: “It can be argued that the regime’s current model of governance is prone to crisis, particularly on the economic front, and that it does not have real solution to Egypt’s pressing problems other than mass repression.”

He does note the level of control over the state, and a limited popular participation, means predicting the regime’s staying power is quite difficult to do: “Indeed, it will only be on the day after its demise, one way or the other, that the full scale of the regime’s folly will become apparent.”

The year 2013 represents a critical juncture in the story of the emergence of a new kind of authoritarianism in Egypt — Sisi came to power in a coup and the Rabaa massacre occurred.

Both events enjoyed large swaths of public support, even though the support was for a more repressive society. Mandour argues the military and Sisi were able to do this as it was able to revive a form of Nasserism, which is deeply entrenched in the Egyptian psyche: “Namely the organic unity of the masses and their natural harmony. This allowed the new regime to frame opposition as treasonous acts, fuelled by foreign powers, aimed at disrupting this natural harmony, allowing the regime to garner popular support for its repression.”

The idea that the Muslim Brotherhood represented treason was not a hard sell to much of the public. Firstly while in power Mohamed Morsi tried to monopolise power at the expense of other groups and interests. Secondly, the Muslim Brotherhood did not curtail the power of security forces, which continued its reign of repression. Thirdly, Morsi abandoned the street protest movement and opted for the ballot box, which alienated the large coalitions built up during the 2011 revolution.

|

In many ways: “The Brotherhood continued to act as a loyal opposition rather than a party in power.” The clumsy policies, breaking up of alliances and not reigning in the security establishment, while at the same time not having full control over the state, made it easy for the military to both remove him and frame it as the will of the people.

Egypt under El-Sisi is without a doubt a necessary read for anyone trying to grasp the basic ways Egyptian political life has been transformed under Abdel Fattah El-Sisi.

Egypt has seen avenues for public dissent shrink but it has done so with either passivity or even support of large chunks of the general population.

The book delves into legal and institutional changes made under Sisi, examines different social policies in which Sisi is both a conservative and a reformer, as well as the increased brazenness in which security forces act in Egypt.

The book provides a framework to understand these developments and gives those interested in Egyptian politics something to ponder and debate.

Where Egypt goes from here will need to be picked up in other books, but this book does provide a solid foundation for them to do so.

Usman Butt is a multimedia television researcher, filmmaker and writer based in London. Usman read International Relations and Arabic Language at the University of Westminster and completed a Master of Arts in Palestine Studies at the University of Exeter

Follow him on Twitter: @TheUsmanButt