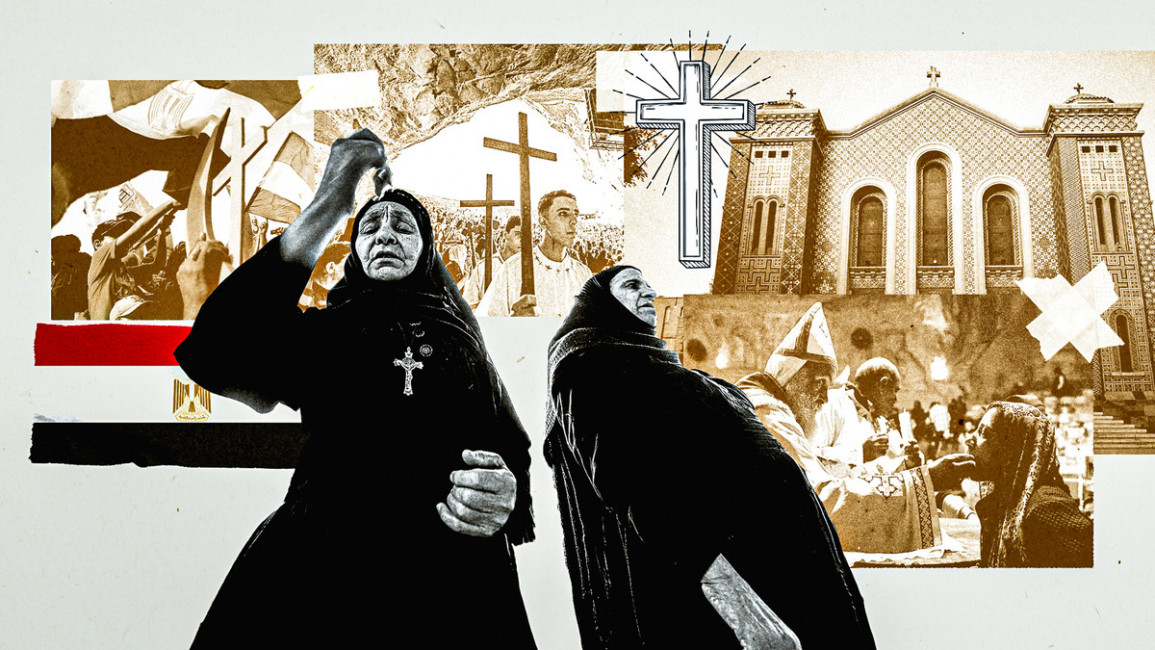

'Behold I make all things new': Life and martyrdom in Egypt's Coptic community

Every year, I am prepared to die.

During Holy Week, the week before Easter, Egypt's Coptic Christian community prays a preemptive funeral prayer in case they happen to pass away that week. If one does die that week, there is no additional prayer offered for them or incense raised on their behalf.

The so-called "general funeral prayer" is a real, genuine, bona fide funeral prayer. With this prayer made, the Church enters a week of grief in remembrance of the Passion of the Christ.

Western Christianity has its ‘Easter Christians’, but Coptic Christianity has its ‘Palm Sunday Christians’,' who come out each year in fear that they might not die a good death. When I was younger and further from the Church, I came out each year so that, if I did happen to pass, at least the fact I had been prayed on would assuage my parents’ grief.

Only now have I come to understand the significance of this week.

"Paradoxically, perhaps it is the Coptic embrace of death that holds the key to a true understanding of the Copts and their identity, one that moves beyond reductionist narratives"

Egypt's Coptic community can't seem to escape death. Its shadow looms long over them. Sometimes, it feels even more senseless than usual. In August of last year, an electrical fire in a Cairo church killed 41 people, including 18 children.

In the wake of tragedy, there is only the talk of death: beyond that, silence. It sometimes seems that the pen of history for the Copts is moved only by death.

Popular narratives of Copts and their history in the West are written without acknowledging Copts' autonomy or how they recognise their own history. In her ethnography, "The Political Lives of Saints," Angie Heo writes, "...Copts are all too often relegated to the 'neo-lachrymose' slot of eternal persecution."

Heo references Salo Baron's idea of the "lachrymose conception of Jewish history." A noted 20th-century Jewish historian, Baron wrote extensively on how Jewish history was written with a near-exclusive focus on tragedy, massacre, and death, which he saw as an incomplete and inaccurate historiography.

Baron argued that for the Jewish people, "Suffering is part of the destiny, but so is repeated joy as well as ultimate redemption." So too must the West expand its conceptions of the Copts.

From its illustrious, heavenly past, today the Coptic language has been largely denigrated to pockets of practice. But embers of the language's revival burn in the diaspora, where second and third-generation Coptics hope to rekindle their heritage ⬇ https://t.co/cmH1mwBIel

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) August 25, 2023

Paradoxically, perhaps it is the Coptic embrace of death that holds the key to a true understanding of the Copts and their identity, one that moves beyond reductionist narratives.

The funeral prayer is a practice wholly unique to the Coptic Church. This ritual, handed down from time immemorial, preserves not only a long-held tradition stretching back to ancient Egypt but encapsulates how the Church approaches death which, in turn, can open new expanses of Western-Eastern reconciliation.

Embracing the history and meaning of this funeral prayer is vital to the project of understanding of Copts in the 21st-century.

To understand this solemn tradition, it's important to contextualise Holy Week, as practised by the Copts; it's a week that's marked by utmost sobriety: strict fasting, no drinking, no marital sex, and prayers from morning to night.

Even in the 21st-century, Copts try to limit their interactions with the outside world as well. They don't use social media. They don't go out with friends. They don't watch any shows or movies.

For a week, Copts become ascetic as they turn together to singularly meditate on the Passion.

The general funeral prayer keeps with this solemnity. Bishop Daniel of Maadi neighbourhood in Cairo writes of the general funeral prayer, "Our participation in the prayers of the General Funeral is voluntary, allowing us to taste the renunciation of the world for a few moments, and to partake in the suffering and death of Our Lord for us, so that we may celebrate His resurrection within us."

And so, this imagined death begins the most sombre week of the liturgical year, with an eye to eventual joy and resurrection.

What is most fascinating about the general funeral prayer is its total uniqueness — the Coptic Church alone maintains this tradition. Not even its sister Oriental Orthodox Churches (Syriac, Indian, Ethiopian, Armenian, and Eritrean) have it.

The closest analogue is Ash Wednesday, the Catholic holy day which begins Lent, on which Catholics receive an ashen cross on their forehead and are reminded of Genesis 3:19 — “For dust you are, and to dust you shall return.”

Across Christendom, different traditions converge in invoking memento mori: remember that you will die, so you must make right before you do. The remembrance of death is a sobering reminder of one's distance from the Divine and the call to dutiful Christian action.

Across visual art, literature, architecture, and almost all domains of human expression, memento mori has become a recurring motif in both Western and Eastern Christianity, but no one has embraced the ideas more than the Copts, who not only remember their death, but take it on.

|

|

Deducing when and where Copts started worrying about whether they might die during Holy Week is difficult — one can only vaguely gesture to sometime in the first few centuries, when Christianity began gaining influence in Egypt and started establishing the traditions it would hand down to future generations.

If there is something meaningful to be said about its origins, it's to be found in the milieu of Egyptian religious society at this pivotal point in its history. In the first few centuries AD, having been subjected to Hellenism and Roman authority, Egypt became grounds for syncretism and the grafting of foreign religion into the strata of Egyptian religious life.

As Egypt became increasingly Christianised, symbols and practices once reserved for the ancient Egyptian religion took on a new valence in the light of Christian belief.

Early Copts sought to distinguish themselves and their religious traditions, and so the co-opting and re-appropriating of ancient Egyptian religious traditions and symbols became an act of defiance and cultural dominance, most prominent among them the ankh.

Once a symbol of eternal life in the ancient Egyptian religion, the ankh came to signify the same, but now through Christ. New liturgical hymns were sung in the tones used in ancient Egyptian worship. Ancient cosmology found a new force of expression in the vernacular of Christian salvation.

On the connection between ancient Egypt and Coptic identity, Annette Evans writes, "From the two rhythmic and predictable miracles of the daily rising of the sun and annual rising of the Nile the Egyptians drew their belief that...renewed life would always be victorious over death. This was the foundational idea of their world-view."

It's not hard to see how this view gelled with the Christian understanding of the Passion and Resurrection.

The ancient Egyptians were obsessed with eternal life and death, and today's Copts see the world through a similar lens. The general funeral prayer feels part of something that has loomed deep within the Egyptian psyche from pre-history to the present.

I'm always struck by the fact that the greatest testament to Egyptian civilization is the pyramids — as towering, monumental, and awe-striking they are, they are grand mausoleums and memorials of death above all.

Of all the ancient wonders, few have persevered like the pyramids. I imagine the Holy Family, during the Flight to Egypt, gazing on them — what must have the child Christ imagined when He saw them? Did he remember His own Death, his own plan to save us? In the sands of Giza, Christ perhaps first saw his Cross.

Maybe this is why over the past two millennia, death has furnished a guiding ethos for the Coptic Church and has become a cornerstone of our self-understanding.

"The talk of death is abstract, but the last decade has brought much of it close to home for the Copts, who face severe persecution. How do they manage to dress their identity in the darkness of death?"

Today, our Church proudly proclaims its identity as "the Church of martyrs." One of the most common protest chants across the Middle East (regardless of religion or nationality) is "By soul, by blood, we redeem you O, ___ !"

Copts chant this refrain with the Arabic word for cross: salib. Copts see their story through blood and flesh, through the repetition of Golgotha, through the conscious and active choices of Copts who have willingly died for the faith.

This is the element that Western historiography misses when it myopically focuses on Copts as victims. Even if Copts do not ask to be martyred, they will meet that fate with joy.

Lest we forget, we are talking about real flesh and blood. The talk of death is abstract, but the last decade has brought much of it close to home for the Copts, who face severe persecution. How do they manage to dress their identity in the darkness of death?

Beshir Kamel, brother to two of the 21 people who were killed by the Islamic State in Libya in 2015, went on Egyptian national TV saying that he and his mother had not only forgiven the killers but prayed for them.

How do Copts celebrate martyrdom, even when their own families are killed? The naïve answer is "faith," but it's the meeting point between Christianity and Egypt that explains why the Copts are so steeled in the face of annihilation.

A few months ago, my mom visited Egypt and sent me a picture of a display case featuring prominent Egyptians, such as Sameera Moussa, Magdi Yacoub, Taha Hussein, and Naguib Mahfouz.

Underneath their portraits was a quote from Pope Tawadros II: "All the countries of the world are in God's hands, but Egypt is in God's heart."

The Church draws from a wealth of Biblical passages to support this privileged view of Egypt. "On that day there will be an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt...they will cry to the Lord because of the oppressors...He will deliver them," reads Isaiah 19:19–20. A few verses later is the famous phrase "Blessed be Egypt My people."

The question of theodicy — of why God allows evil to exist — continuously troubles all Christians, but many Copts choose to remember these passages to give themselves comfort. Maybe not today or tomorrow, but deliverance for the Copts is promised.

|

|

Our two thousand year-long history begins with the martyrdom of our founder, St. Mark, being dragged through the streets of Alexandria. That history will likely continue to be told in blood.

Yet, death may very well be part of our deliverance. In response to the execution of 21 Copts in Libya, the world turned its eyes on Egypt, and no one could have anticipated just how far-reaching the consequences of their martyrdom would be.

In May of this year, Pope Francis met with Pope Tawadros II at the Vatican and announced, in an unprecedented move, that the 21, who were already revered as Coptic saints, would be added to the Roman Martyrology.

Many were surprised, perhaps for good reason — the Coptic Church broke off in the 5th century, and since then, the two Churches have diverged in practice and theology. The Catholic Church has made efforts, beginning in 1439 with the Council of Florence, to court the Coptic Church, but for one reason or another, these efforts have been unsuccessful.

Perhaps this is the first real and true ecumenical step towards reconciliation of the fractured Church.

"We took on the façade of death for a week — with that faith, there is the quiet assurance: we will be made new"

On the night of Good Friday, Copts celebrate Apocalypse Night. From midnight until sunrise, the Book of Revelation is read in its entirety. In the penultimate chapter, the deacon reads about the new creation, a new glorified Heaven and Earth where there is no sorrow.

"Then He who sat on the throne said, 'Behold, I make all things new.'"

On Easter Eve, Copts flock to midnight mass in their Sunday best. The solemnity of the past week melts away as Copts celebrate Easter with zaghrootas and go home to break their two-month-long fast with family and friends.

On Sunday afternoon, they died to taste Christ's Passion, and the next Sunday, they are raised in joy with the Resurrection.

As we say, "Christ is risen from the dead, by death trampling death, and to those in the tombs granting life." We took on the façade of death for a week — with that faith, there is the quiet assurance: we will be made new.

George Iskander is a PhD candidate in physics as well as a cinephile and writer.

Follow him on Twitter: @jerseyphysicist

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

![Every year, before Easter, Egypt's Coptic community holds a funeral prayer, taking on death for one week to then be resurrected. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/1240157075.jpeg?h=790be497&itok=Cg92wROr)

![Egypt's Coptic community has long faced persecution and violent attacks. In August 2022, a church fire killed dozens. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/629135302.jpeg?h=b347c549&itok=Fy_fU69X)